We Pit Cup Noodles Against Cup Noodle and the Difference Is Real

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Why are American Cup Noodles so bad when Japanese Cup Noodle is so good?

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

You may know Sho Spaeth as the editor who developed not one but three different recipes for homemade ramen noodles. Fun fact: He's just as happy to nerd out on the store-bought stuff, and this story was originally published as part of a column about instant noodles. The opinions expressed are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Serious Eats staff.

When I was a child I had a difficult relationship with the truth.

I’m not saying I was a liar. Nor am I saying I had difficulty distinguishing reality and fantasy, the world as it was and the world as it existed in my mind. But I did have a tendency to believe that what was true for me was necessarily true for everyone else. Like all children, although I couldn’t put it in these terms at the time, I believed my experience to be universal.

And so I believed that everyone loved Cup Noodle. Not just that: I believed everyone, everywhere, loved Cup Noodle as a general proposition, but also loved Seafood Cup Noodle in particular. That when their mothers (because everyone in the world, forever, had a mother) came home one day from playing bridge with her Japanese friends (because everyone’s mother, of course, played bridge with her Japanese friends) and opened up a bulging plastic bag filled with Styrofoam cups riddled with indecipherable chicken scratchings, but otherwise emblazoned with “Cup Noodle SEAFOOD Noodle,” the “SEAFOOD” bisected by a lazy water line to denote the sea from which all the dried stuff inside had been fished from, they used the rudimentary math at their disposal to calculate, at one Seafood Cup Noodle a week, how many weeks of Cup Noodle they could look forward to.

But I grew up; I traveled the world; I did away with childish things. I came to understand that my truths were not universal. And while I know it’s wise to recognize the limits of your objectivity, to understand that what is true for you may not be true for anyone else, and that this is what we argue about when we say, “There’s no accounting for taste,” or, “To each their own,” I must confess that on the issue of Cup Noodle, and Seafood Cup Noodle in particular, I possess a latent sense that my truth, although perhaps not universal, nevertheless should be.

Which is a long way of saying I think Cup Noodles are bad.

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

If that sounds a little confusing, I suppose it is. But the fault isn’t mine, and the confusion is easily cleared up with a little bit of instant-noodle history.

As is widely known, in 1958, Momofuku Ando, a Taiwanese immigrant living in Osaka, Japan, invented instant noodles. By deep-frying fresh, seasoned, steamed noodles, he created a tasty, shelf-stable product that, when combined with boiling water, could be ready to eat in just two minutes. Ando’s innovation created the instant noodle market and, thus, changed the course of culinary history.

About a decade later, Ando came up with a related innovation, similar, if not exactly an equal, in its impact to the creation of instant noodles as a category of food. As the story goes, while in the United States to demonstrate his revolutionary instant-noodle creation, he watched as supermarket managers chose to transfer their instant noodle packets and seasoning to plastic cups*, into which they then poured boiling water.

*Those plastic cups, too, were a relatively recent innovation: What many call Styrofoam (which is actually an extruded polystyrene, used in construction) is an expanded polystyrene that was developed in 1954.

Ando was intrigued by those cups, and he spent the next several years developing what would eventually be unveiled in 1971 as Cup Noodle, an instant-noodle product that was sold in a waterproof, insulated expanded polystyrene cup, which served as both packaging and serving container. So far, so clear.

But things got a little tricky when Ando and his Nissin company decided to enter the American market. In 1973, Nissin began selling “Cup O’Noodles.” The changed name, which eventually transformed to the “Cup Noodles”—with an ‘s’—that we in the United States know today, was more than just a change in branding for the new market; it was also an outward indication that the contents of the polystyrene cup were different than their Japanese, “Cup Noodle” counterpart. Nissin came up with new flavors for the American market—originally, beef, chicken, and shrimp varieties were offered—and changed the noodles, because during that fateful trip in which Ando was introduced to the miracle of expanded polystyrene, he also observed that the American supermarket managers broke up the noodles before cooking, and ate them with forks. To accommodate these cultural preferences, Nissin made the noodles shorter.

And in the process, Nissin made a product that was similar to the wonderful original, but it was different, because it was bad.

To be fair, I don’t actually know whether the first Nissin Cup O’Noodles products were bad; I wasn’t alive when they were introduced. But I do know every American Cup Noodles product I’ve ever eaten has tasted bad, and has had bad noodles, and every Japanese Cup Noodle product has been passable-to-good, with legitimately good noodles.

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

About a year ago, in the spirit of embracing the vast variability of human experience, and with the understanding that my taste preferences are mine and mine alone, dictated by my early exposure to a specific range of Cup Noodle (no ‘s’) products, I contacted Nissin Foods USA and asked whether they’d be willing to send a Serious Eats representative (me) samples of their various product lines from around the globe. A representative from the company suggested this would be impossible, although they were gracious enough to send along the entire range of American products. This included two flavors from the Japanese market that are made available to American consumers—my favorite, Seafood, and Curry (which is very, very good, too)—and which are conveniently distinguishable from other American products because they use the singular “Cup Noodle” on their packaging.

While I was disappointed by not being able to try such alluring options as “Cup Noodles Mazedaar Masala,” the more pressing issue was that I had a bunch of bad Cup Noodles products and a couple of good Cup Noodle products and I didn’t know what to do with any of them. With a vague idea of trying to compare American Cup Noodles to their Japanese Cup Noodle counterparts, I asked my aunt in Japan to ship me the entire range of Cup Noodle products available at her local grocery store.

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

When they arrived, I set out all the American Cup Noodles products and all the Japanese Cup Noodle products, and two things jumped out at me: The Japanese flavors were a little more enigmatic in their descriptions (“miso,” “salt,” “seafood,” “curry”), whereas the American ones were more descriptive (“chicken,” “hot and spicy shrimp,” etc.). But, of greater interest to me, particularly as someone trying to determine why they like one class of products so much more than the other, was the quality of the packaging: The Japanese polystyrene cups seemed sturdier and better constructed.

Fresh off the last instant noodle column (which was also the first), I believed it might be possible that the quality of American Cup Noodles products suffered because of the quality of their packaging, and that seemed like something I could test. The working hypothesis, based on the testing I did on Shin Ramyun packets versus Shin Ramyun cup products, was that the inferior construction of the American Cup Noodles products’ packaging directly contributed to the inferior quality of the cooked product.

I set up a series of tests. First, I compared the American Cup Noodle Seafood flavor with the Japanese Cup Noodle Seafood flavor, since they were most similar to one another of all the products. For the second test, I compared the American Cup Noodles Chicken flavor with the “original” Japanese Cup Noodle flavor. Then I performed both tests again, but I emptied the contents of the American Cup Noodle Seafood flavor and transferred it to a Japanese Cup Noodle packaging and vice versa. I did the same with the American Cup Noodles Chicken flavor and the “original” Japanese Cup Noodle flavor. In each test, I prepared the noodles as instructed by the packaging, then tasted both the noodles and the soup.

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

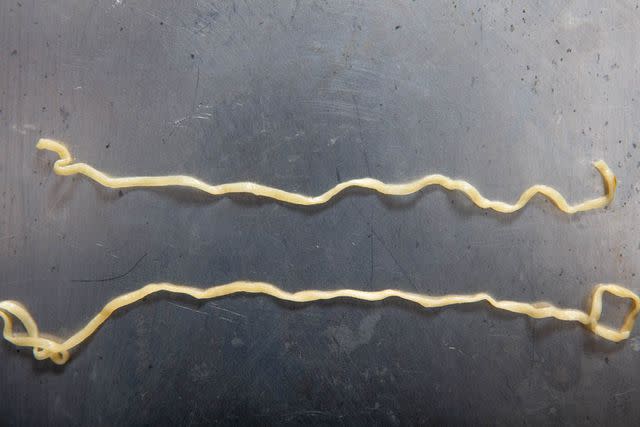

In this first photo you can see the American seafood-flavored Cup Noodle noodle on top, and the Japanese seafood-flavored Cup Noodle noodle on the bottom. The American noodle was softer, with less bite, and was noticeably shorter. The broths, even though they are ostensibly the same product, were noticeably different; the most overt difference being the stronger flavor and aroma of ginger in the American one.

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

In this second photo, you can see the American chicken-flavored Cup Noodles noodle on top, and the “original” Japanese Cup Noodle flavor noodle on the bottom. The top noodle is clearly a different color, and its texture was, if anything, softer than the American seafood-flavored noodle. Similarly, the Japanese noodle was longer, with a more pronounced bite.**

** My tasting notes for this test merely reflect my taste preferences: American Cup Noodles are bad (“canned chicken” “why?” “yuck”), Japanese Cup Noodle is good (“mmm,” “yes,” “that flavor," "when it touches your lips”).

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

In this third photo, you can see the results of cooking the noodles in their counterparts’ packaging (the American Cup Noodle seafood-flavored noodle cooked in a Japanese Seafood Cup Noodle cup on top). The American noodle, in contrast to the previous two photos, looks glossier and looks snappier—and it was. The Japanese noodle, by comparison, was a little softer, with less bite, and, unaccountably, was a bit paler. In terms of taste, they were pretty similar, but the American noodle had the slight edge.

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

Finally, in this photo, you can see the results of cooking an American chicken-flavored Cup Noodles product in a cup for the “original” Japanese Cup Noodle flavor on top, and vice versa, on the bottom. The Japanese noodle seemed to benefit by the swap, although the noodles seemed more prone to break, and thus lost their lovely length, whereas the American noodle seemed to be mostly the same—flaccid and mushy, not fun to eat at all.

I was a little mystified by the result, as it seemed to disprove my hypothesis: The American Cup Noodles packaging seemed quite well-suited to cooking noodles well, and seemed to have an appreciable, positive effect on the Japanese noodles.

I did another round of testing, but this time just to see how successfully each of the polystyrene cups (the American Seafood Cup Noodle, the Japanese Seafood Cup Noodle, the American Chicken Cup Noodles, and the “original” Japanese Cup Noodle) insulated their contents. The idea here, as with the Shin Ramyun cup test, was that the temperature of the cooking water has a direct impact on the qualities of the final cooked noodle, and tracking how hot each cup kept the boiling water would give some insight into what was going on with the noodles.

For the test, I poured 200ml of boiling water into each cup, inserted an instant-read thermometer, covered the cup, then tracked the water temperature at four points: right after pouring the water, after one minute, after two minutes, then after three minutes. I repeated the test three times, and then I repeated it again, but instead of using 200ml of water, I simply filled each cup to its “fill-line.”

To my surprise, the American Chicken Cup Noodles cup was the best insulated. In every test, after three minutes had elapsed, the water temperature held steady at 199°F. By contrast, the boiling water poured into each of the Japanese cups typically ended up at around 194°F, give or take a degree. The Japanese Seafood Cup Noodle cup, which looks and feels like it is of better quality than all the others, wound up with water at 192°F at the end of three minutes in two rounds.

Serious Eats / Vicky Wasik

So what to make of all this (basically useless) information? How do we explain that Japanese Cup Noodle products, cooked in American Cup Noodles containers, are moderately improved? Or that the American Seafood Cup Noodle is improved by being cooked in the Japanese Seafood Cup Noodle cup?

My working theory is that Momofuku Ando wasn’t a fool. I believe it’s safe to assume that the man who revolutionized packaged food not once, but twice, knew what he was doing.

The texture of American Cup Noodles noodles, which I find so utterly unappealing—soft, with little snap, perfect for globbing on a fork but irritating to pick up with chopsticks, meant to be mouthed in one bite rather than slurped up in a rush of pleasure—is exactly as it’s meant to be, and the same goes for the Japanese Cup Noodle noodles. Swapping containers indicates as much: The higher sustained heat of the American Cup Noodles packaging produces some beneficial effects in the Japanese Cup Noodle noodles—glossier, snappier—but then messes with the noodle integrity, too, resulting in shorter noodles. The lower sustained temperatures in the Japanese packaging produce American noodles that are slightly less overcooked, giving them character where character is unnecessary, or at least beside the point.

All of which is to say, Nissin knows what its products should taste like in any given market in order to have maximum appeal. You see this in the packaging—Americans prefer recognizable flavor descriptions like “chicken,” whereas Japanese prefer recognizable flavor descriptions like “salt,” and Indians like recognizable flavor descriptions like “mazedaar masala”—and you see it in the product itself—Americans prefer soft, gummy noodles, the better to sponge up chicken noodle soup–flavored slop, Japanese prefer snappier, harder, longer noodles, the better to slurp up seafood-inflected soups in variety.

And while I might think all American Cup Noodles flavors are bloodless; that their noodles are more fit for babies than any self-respecting, noodle-loving adult; and their packaging is entirely unappealing, just from an aesthetic standpoint; those are simply my opinions, not universal truths. Those opinions are based on a very specific set of cultural circumstances, starting with my Japanese mom and her bridge-playing friends, maintained by my steady diet of Japanese Seafood Cup Noodle products purchased from the Japanese supermarket on the ground floor of the Serious Eats office building.

I am no longer a child, so I don’t think that my opinion has any better claim to the truth than anyone else’s. I say, eat the Cup Noodle(s) products you want to, and enjoy them as you will.

February 2020