The pioneering TV dramas that have changed Britain

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

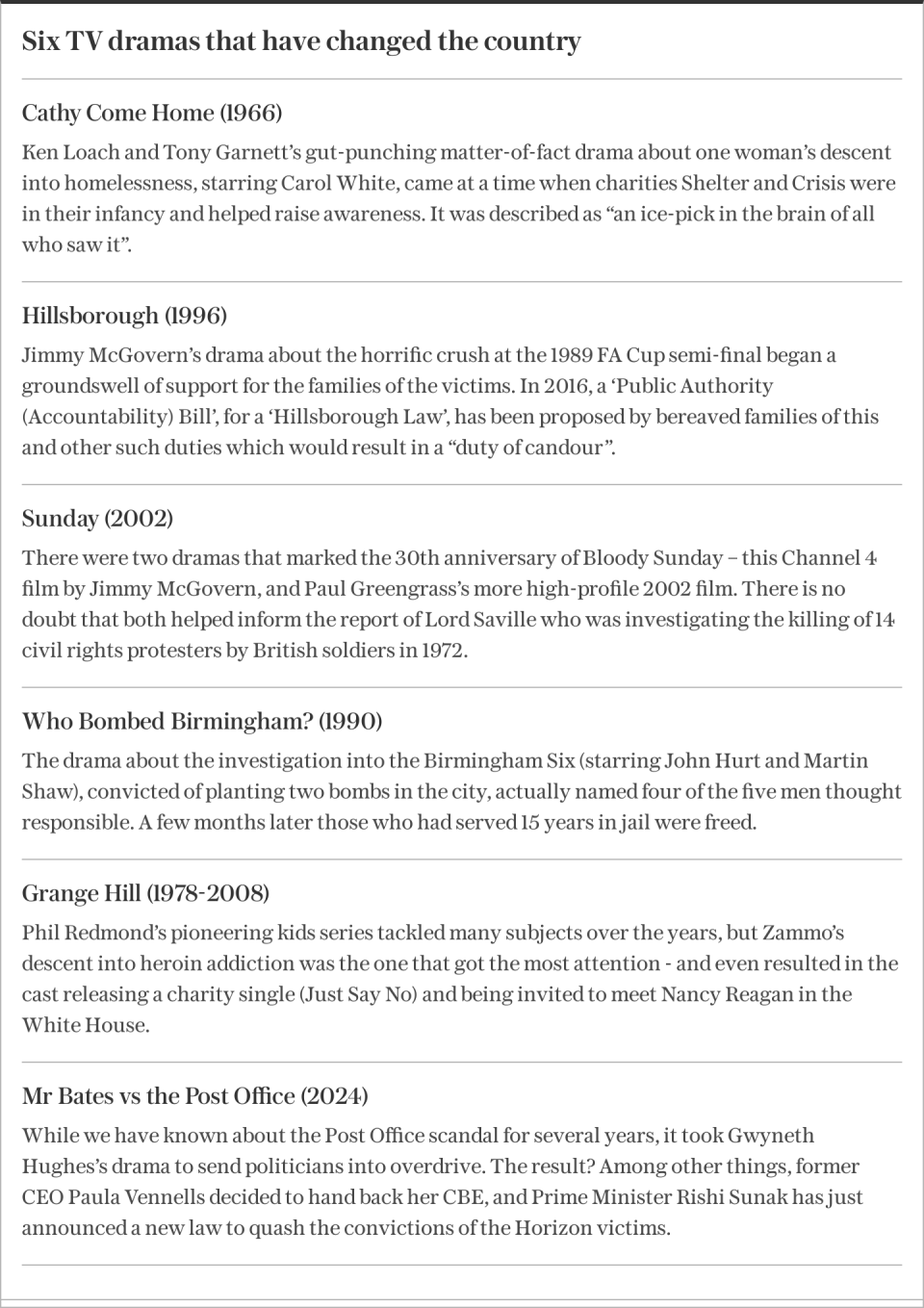

It was 2009 when a journalist first reported that something had gone very wrong at the Post Office. By then, when Rebecca Thomson wrote about it in Computer Weekly magazine, problems with the Horizon accounting system had already been destroying lives for a decade, and the long steady trudge towards justice had begun, almost unnoticed. Now, nearly 25 years on, ITV’s Mr Bates vs. The Post Office has blown the doors off the scandal. This grave miscarriage of justice is not only front-page news, but the Prime Minister has just announced that outstanding convictions will be quashed. Such is the power of television drama.

Yet it’s something that these days we only rarely see on our screens: crusading, agenda-setting TV, of the people, for the people. Gwyneth Hughes’s drama, starring Toby Jones as the real-life Alan Bates, shows how easily this could have happened to any one of us. The former sub-postmaster was betrayed by a system that was viewed as incapable of being wrong – or as a judge ruled in awarding £321,000 of costs against another victim, Lee Castleton (Will Mellor), in episode one. “The conclusion is inescapable, that the Horizon system was working properly in all material respects” – it wasn’t – “and that the shortfall is real” – it wasn’t – “that the losses must have been caused by Mr Castleton’s own error” – they weren’t. Homes, savings, reputations and even lives were lost to those assumptions.

Hughes’s writing has brought it all into emotional focus, in a way that can’t be ignored. Events since the four-part series aired have shown how a drama can effect change in a way that documentary perhaps can’t, by the power of story and the sheer weight of numbers that respond to its telling, with talented actors and a script tuned to elicit emotion. Documentary might give us Paula Vennells’s comment to a select committee: “This is about the reputation of the Post Office”, but it may not offer us the response of Julie Hesmondhalgh’s Suzanne from her living room, “What? No it’s not, it’s about people’s lives, you moron.”

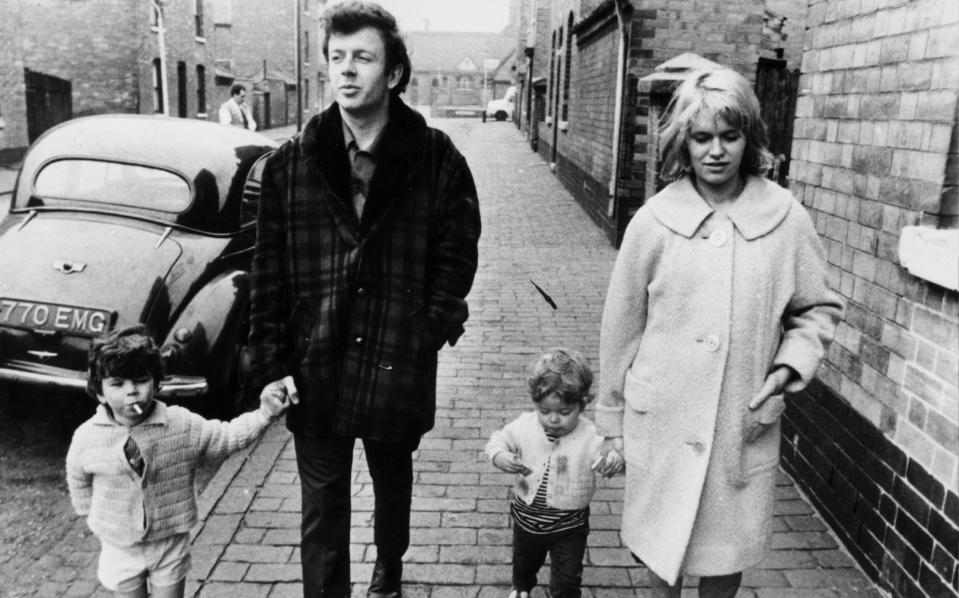

Of course, it’s not the first crusading TV drama. British television has a proud history of them. In 1966, Cathy Come Home, the 80-minute film Ken Loach directed for BBC One’s The Wednesday Play, captured the plight of a young mother driven towards homelessness. It caused such widespread public outrage that questions were raised in the House of Commons. Loach was a pioneer, alert to the potential that television offered in reaching an audience far broader than that of the traditional theatregoer, and he was determined to expand the possibilities of TV drama beyond reworking stage dramas for viewers at home.

He was followed by a generation of writers prepared to take on social issues of the day. Phil Redmond altered the landscape of children’s TV in 1978 with his secondary school drama Grange Hill, which would go on to tackle bullying, drugs, teenage pregnancy, AIDS, sexual assault, racism and other issues. In the same year, Jim Allen’s The Spongers for BBC One’s Play for Today showed the effect of welfare cuts on the elderly and disabled people. In 1982, Alan Bleasdale confronted the nation with the reality of unemployment in Boys from the Blackstuff. Yet since then, such dramas have been more infrequent than one might imagine.

Television began expanding, “It was a whole new sexy area”, Redmond says, while its old guard, he adds, steeped in the principles of public service broadcasting were out, supplanted by people “who just wanted to be in telly”. Campaigning dramas are not “sexy TV” and don’t lend themselves to easy-to-recommission long-form series. And as international streaming services such as Netflix increasingly dictate the agenda, TV makers increasingly chase global hits. The very British story of Mr Bates would likely never be commissioned by a streamer. Yet when such “local” stories hit home, they hit hard.

In 1990, five years after ITV’s World in Action first laid bare the appalling treatment that led to the false confessions of the six men convicted in 1975 of planting deadly IRA bombs in two pubs in Britain’s second-largest city, the channel aired Who Bombed Birmingham?, a drama based on the investigation. The original series had unearthed new evidence, which had been rejected out of hand at the Court of Appeal, but the TV drama went so far as to name four of the five IRA men believed to be responsible. Less than six months after it aired, the “Birmingham Six” were freed.

A similar marriage of hard-hitting journalism with TV drama was one of the reasons why Jimmy McGovern’s Hillsborough struck a nerve, according to the screenwriter. “The best thing we did was we got Katie Jones from World in Action on board,” McGovern tells me over the phone from his home in Liverpool. “She made sure everything was meticulously researched.”

McGovern had a simple starting point for the 1996 drama about the fatal crush that occurred at the 1989 FA Cup semi-final in Sheffield. “I wanted to break people’s hearts at the injustice of what had happened.” The intent of the two-hour reconstruction of events at Hillsborough and their aftermath was novel, he believes, “I didn’t think it had ever been done before. In Hillsborough, we were accusing the South Yorkshire Police of the manslaughter of 96 people” [now 97].

These days, McGovern is recognised as the premier exponent of drama with a social conscience. He has addressed the need for prison reform in Time, the unfairness of the joint enterprise law in Common and the case against the Iraq War in Reg. But his 2002 drama Sunday, about the events of Bloody Sunday in Derry in 1972, came about because he was unable to turn his head away. “I’m not an Irish republican, I’m an English patriot, but I just wanted to tell the truth,” he says. “I knew we’d been fed a pack of lies.” The drama preceded a similar verdict from the Saville Inquiry by eight years.

Yet it was the huge success of Cracker that first allowed him to set off on a new path with the commissioning of Hillsborough. McGovern knew he would meet a Granada drama executive – the late Andrea Wonfor – at the Baftas but still waited until the evening was a few brandies in before pitching his idea. The reaction to the drama, though, surprised even its writer. “I thought it was bound to be reviewed, so I was looking at the TV pages. But, of course, it was all over the news pages.”

The same is true of Mr Bates vs. The Post Office. Yet McGovern says that it is important that campaigners push home their advantage while it is there. “What drama-doc does is, for a short while, it changes the agenda. Suddenly, the one that was set by the programme is the agenda that everybody has to answer to. And that’s a godsend for people fighting for justice.” But he notes, “the hoo-hah will die down, and the people will be left to go on fighting. Tony Blair and Jack Straw did absolutely nothing to help with Hillsborough, so the energy that was built with the drama-doc dissipated, because there was a lack of action.” Perhaps in the age of social media, impetus once gained is unstoppable.

Phil Redmond, who directed the public’s attention to the issue of domestic violence and the laws surrounding premeditation in Brookside, with a storyline about the murder of the abusive Trevor Jordache by his wife and daughter, says that the soap “allowed the real campaigners, like Helena Kennedy and Cherie Booth, who had been campaigning on this issue for years” to take advantage of the emotion generated by the show to put it squarely on the front page. Across the board, soaps have raised awareness on important issues, from the right to die, coercive control and child grooming in Coronation Street to knife crime and suicide in EastEnders.

Yet, at times over the past two decades, despite the efforts of McGovern and the socially committed writing of Jack Thorne in works such as the Covid care-home drama Help, it has appeared as if crusading television is a thing of the past. Redmond believes that a confluence of factors led to a loss of courage in TV commissioning during the Nineties, beginning with the 1990 Broadcasting Act, which could bring draconian fines from the regulator for causing offence, which Redmond says, was “because of pressure from the government over the ’80s about television being out of control, too controversial, attacking the government”. The inevitable result, he says, was “self-censorship”.

Meanwhile, the threat of new channels and platforms diverted channels towards “programming that would attract the biggest audiences for the least expense – that was where reality TV started”. In the 1970s and ’80s, Redmond suggests, TV would have picked up on the Post Office scandal “six or seven years in” not 25. Yet he admires the drama’s “total respect for realism, all the way through” and how Hughes made a virtue of “one simple thing – there’s no need to overdramatize an already very dramatic situation”.

Perhaps the drama will even affect TV’s future. Redmond hopes that the public’s response to Mr Bates vs. The Post Office will have given television bosses pause to ask themselves, “do we need another dysfunctional police officer? There must be other stories out there, plenty of stories.”