A Pioneering LGBTQ+ Scholar Once Hid Her Mom’s Queer Books

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

During Abbie Goldberg's preteen years, her mother divorced and then met and fell in love with a woman. But the status of her mother's new romantic relationship was unclear. “We called her ‘godmother’ or ‘my mom's best friend,’” says Goldberg of herself and her two siblings, a younger and an older brother. "My mother wasn't saying it. She wasn't naming it. And to be honest, I don't know that I wanted her to. We had a shared understanding that there wasn't really a place for this in our suburb in ’80s New York," she recalls, pointing out the conformist thrust of that era amid Reagan's ultra-conservative presidency.

As a teen, she would scan her mother's bookshelves for titles with lesbian references and flip their spines so her friends wouldn't see them. By then she says it was less about shame-infused secrecy than a missing set of common cultural terms through which to articulate their kind of family being accurately seen and understood. "There was no vocabulary. There was no context," she says.

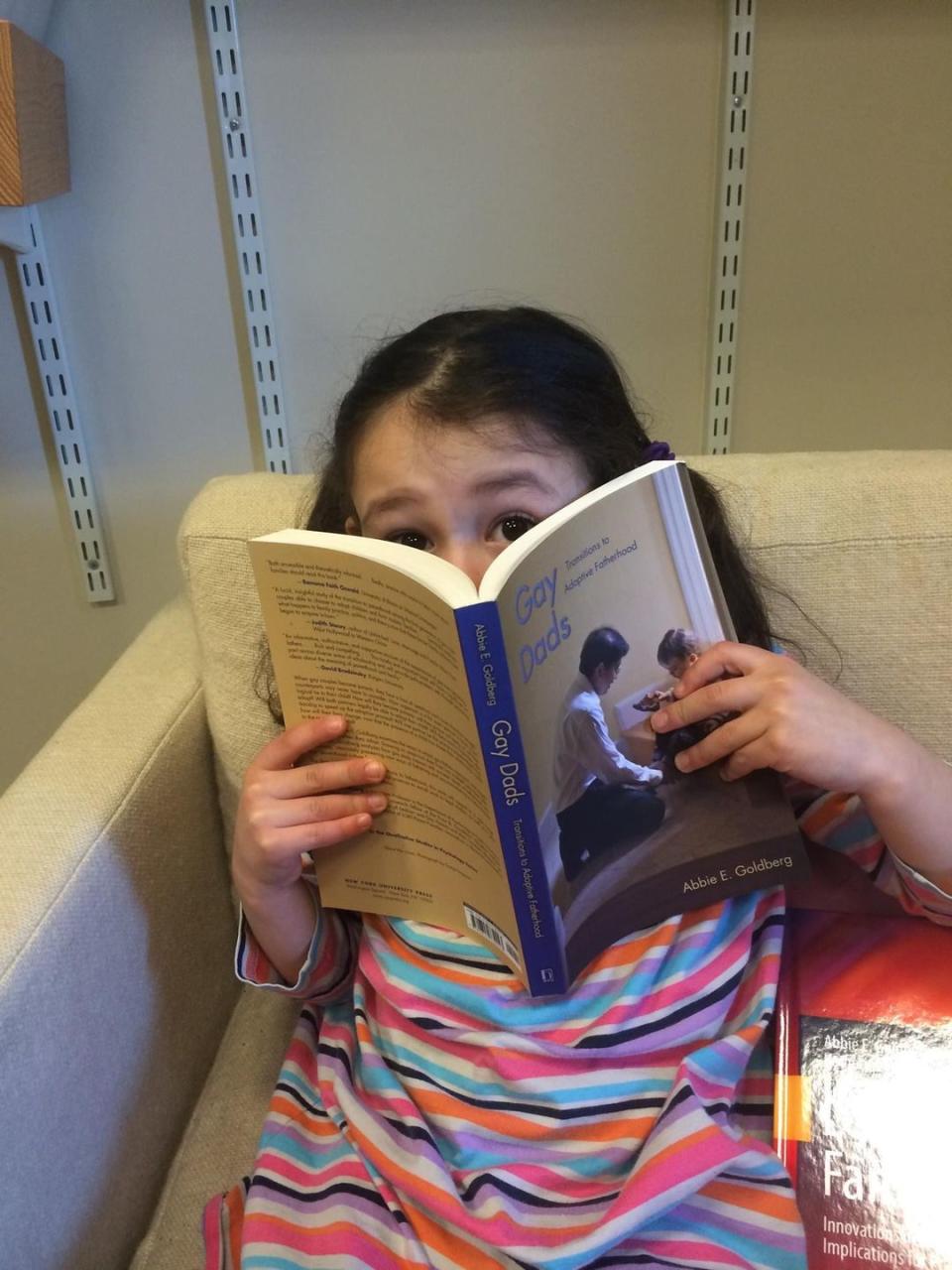

Today, Goldberg has not only written books—Lesbian and Gay Parents and Their Children, Gay Dads, Open Adoption and Diverse Families and LGBTQ Family Building—that would make her younger self balk, as a pioneering LGBTQ+ family studies scholar in Clark University's department of psychology, she's dedicated her entire career to researching and raising awareness about the inner workings of LGBTQ+ family dynamics and their experiences in the world.

One of the central goals of Goldberg's work is to help people and society break free from the shackles of compulsory silence around certain topics—having queer family members or fraught (or nonexistent) relationships with parents or siblings, for example—after experiencing and witnessing the damage and pain it causes. "A big influence on where I've gone with my work is that I don't want anyone to ever be so fearful that a parent's being gay is somehow going to alienate or isolate them from their relationships or become a barrier to them achieving what they want to achieve," she says, pointing out that three of her six best friends came out in college. "We were all keeping secrets," she says.

Recently, Goldberg sat down with Oprah Daily over Zoom to reflect on her career and how she hopes her research will better inform the public, future scholarship, and public policy as it pertains to queer families.

When did your mom actually come out to you?

Not until I was 16. She told me that a big reason why she waited to say those words was that it was very easy for queer women to lose custody of their kids back then. All these lesbian moms lost their kids to their heterosexual ex-husbands in the 70s and 80s. And I knew that had my dad been a different person that absolutely could have happened to us, which partially inspired my work.

You've come a long way since flipping the spines on your mom's books. Tell us a little about how you ended up studying and becoming the foremost scholar on LGBTQ family studies.

I was always interested in family. That partly comes from my own family and how complex it was and how invisible it was in the larger landscape of families, but I don't know if I processed it that way at the time. As a Ph.D. student, I was working with a professor who was studying how working-class families with fewer resources make the transition back to work after the birth of their first child. In that context, I became interested in another kind of family that's invisible, LGBT families. I was watching gay and lesbians friends of mine try to get pregnant or how they were mistreated, even in a progressive state like Massachusetts, by the hospital system.

My dissertation was the first in-depth study of the transition to parenthood for lesbian couples. A lot of prior research on LGBTQ families centered on wanting to show that the 'kids are alright,' which was very much in response to moms losing custody and that work was really important. But I was really interested in what happens within families as opposed to just establishing that these families are okay. I wrote early papers on things like how having gay parents affect kids; how they make decisions about disclosure; how and when they tell people; how do they think their own ideas about sexuality and gender and parenting have been impacted by having gay parents?

You've also written about the unique challenges gay dads face in a world that puts moms on the mightier parenting throne.

There are still a lot of assumptions around children needing a mother or maternal figure in order to develop properly. We think of fathers as kind of 'extras' in society in some ways. But mothers have a unique role in that they are seen as both necessary, but also subject to extremely high standards and significant critique. So we're basically responsible for everything bad and good. But gay dads face a lot—questions around how they are going to provide a maternal figure to this child, assumptions about two dads being essentially redundant, really old gross stereotypes about gay men and pedophilia that are totally unsubstantiated, or unfounded beliefs about how they'll socialize their children into homosexuality. And certain behaviors in their children are often over-interpreted because they don't have a mother. It all creates a lot of stress and anxiety.

You've also written several papers on the experiences of transgender or gender non-conforming children and I wondered if you'd speak a little about the ethos around supporting trans kids in their transition that makes asking questions as concerned parents difficult. Questioning can be read as a form of challenging your kid's gender identity or sense of self.

If I didn't have the research background on this topic and my kid wanted to go on puberty blockers, I'd be asking lots of questions. It's not like parents are simply supportive or not supportive. Being affirming of your child doesn't mean unquestioned allegiance to whatever the kid wants. Being a caring parent means asking thoughtful questions about how any choice your child makes now may make impact them in the future. At the same time, it's very important to listen to what your children are telling you about themselves.

What are some of the changes you'd like to see in the educational system to improve the experience of LGBTQ students or children of LGBTQ parents?

I've created the Teach All Families curriculum to provide materials based on my research for parents and educators to create greater inclusion for families at school. It suggests things like Parent's Day as opposed to Mother's Day or Father's Day. Family trees can be potentially harmful since they are usually based on bloodlines so the curriculum tries to get educators thinking about family more holistically. There are so many assumptions baked into the way we talk about families in education. Providing more expansive ways for people to identify on school forms with gender-neutral labels like parent or caregiver is helpful, too. I want families and teachers to be way more explicit about inclusive language. It could really help not just LGBTQ families, but all families.

What other kinds of impact do you hope your work will have on individuals and society?

I want people to be able to validate and acknowledge all kinds of families. I want people to feel free to ask questions that are hard. I would like this work to not be so politicized. I don't want our research questions to be driven by fear about how the data might be used against our families. Nobody should ever have to prove in court that they're a good parent just because they are an LGBTQ parent or should have to challenge or confront any stereotypes about mental illness and homosexuality.

On that note, what does Pride Month mean to you? Is it as important as it's been in the past?

Now more than ever, LGBTQ people and allies need to feel a sense of community, solidarity, and shared commitment to both fighting back against the current and ongoing injustices against the LGBTQ community, and also celebrating the diversity and beauty of the community. It is easy to feel defeated, angry, and scared. But to me, the annual celebration of Pride is a reminder of the strength, energy, humanity, fire, and love that exists and which we need to keep going.

You Might Also Like