Pioneering Feminist Artist Lynn Hershman Leeson Gets Timely and Overdue Attention in a New Show

There’s a lot to process at the Shed’s new show Manual Override, which opened this week in a dark, curtain-hung space carved out of the Griffin Theater. “Process” seems like the right verb, since the show, according to curator Nora N. Khan, is intended to interrogate the “material ways that technology replicates systems of oppression.” The exhibition includes a “5-D” (what those additional dimensions are, I’m not quite sure) experience by Simon Fujiwara that has participants strap themselves into a flight simulator, and a video by Martine Syms in which visitors can control, via text message, the way the installation manifests. Manual Override, as Khan put it, is gesturing to the idea that the off switch may no longer be an option.

But there’s another simpler but no less powerful way to engage with this complicated exhibition. See it for the installations dedicated to pioneering artist Lynn Hershman Leeson, who, after decades of relative anonymity, is finally getting a level of acclaim that male peers engaged in similar pursuits have long received. “Others my age with lesser work who were men were being celebrated and collected,” she told Frieze last year. “I was discovered when I was 72.” The discovery comes not a moment too soon, as Leeson’s work engages with the pressures of self-presentation, deception, and artifice that undoubtedly saturate an Instagram feed near you.

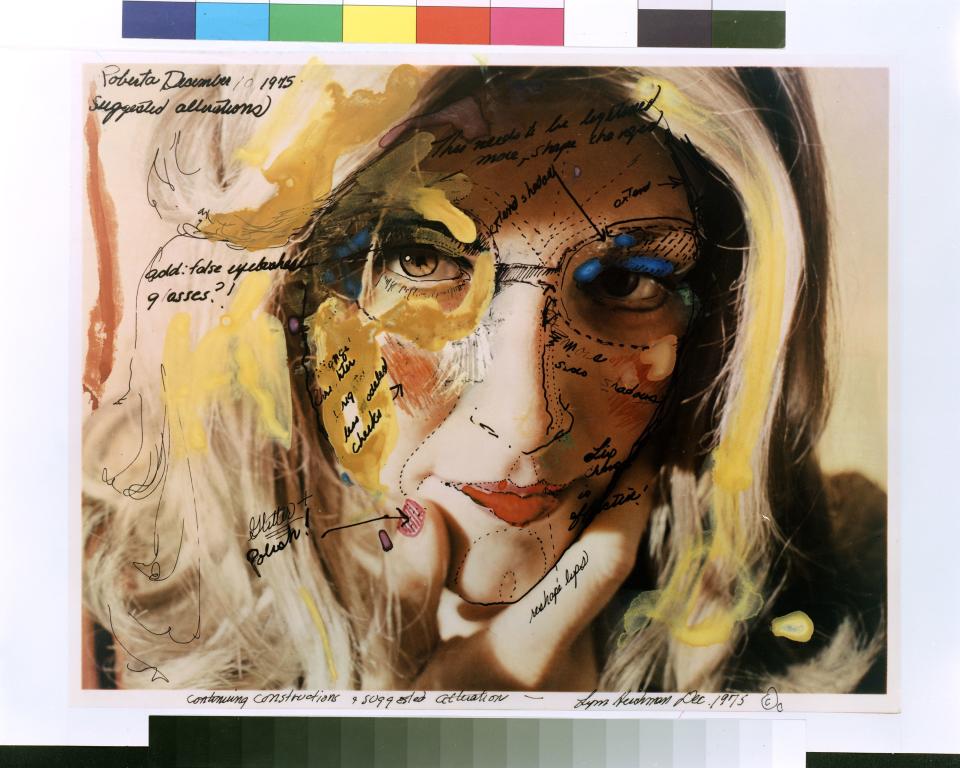

Leeson has been engaged in this work at least since 1972, when she famously (at least, as famously as can be expected for an avant-garde, under-the-radar artist) invented a character named Roberta Bretimore. To inhabit this character, Leeson wore a blonde wig, applied a carefully designed face of makeup, and set her alter ego loose in the world.

01 Lynn Hershman Leeson.jpg

Roberta not only interacted with the world, leaving untold personal impressions, she left the documented detritus of a life: an apartment lease, dental records, therapist appointments, a Weight Watchers membership. (Leeson later had actresses other than herself fulfill the role.) While visiting the San Diego zoo, the character was even asked to join a prostitution ring, according to the artist.

Before identity became cataloged by our online banking habits, facial scans as we pass through TSA security lines, and the items we leave unpurchased in our digital shopping carts, destined to haunt the peripheries of our browsing windows, Leeson was concerned with the ways in which identity could be built by perhaps specious markers in the world. Roberta, Leeson has said, was able to qualify for credit cards that Leeson was not. Did that make Roberta more of a person than her creator?

In some ways, that awkward but direct formulation is the central question of Leeson’s work: What is a person? Take Leeson’s 2002 film, Teknolust. At the time of its release, Teknolust was called by The New York Times, “a minor addition to the tiny genre of feminist science fiction films.” (MoMA has since acquired it for their permanent collection.) In it, Tilda Swinton played a scientist (“Rosetta Stone”) who uses her own DNA to create three clones of herself.

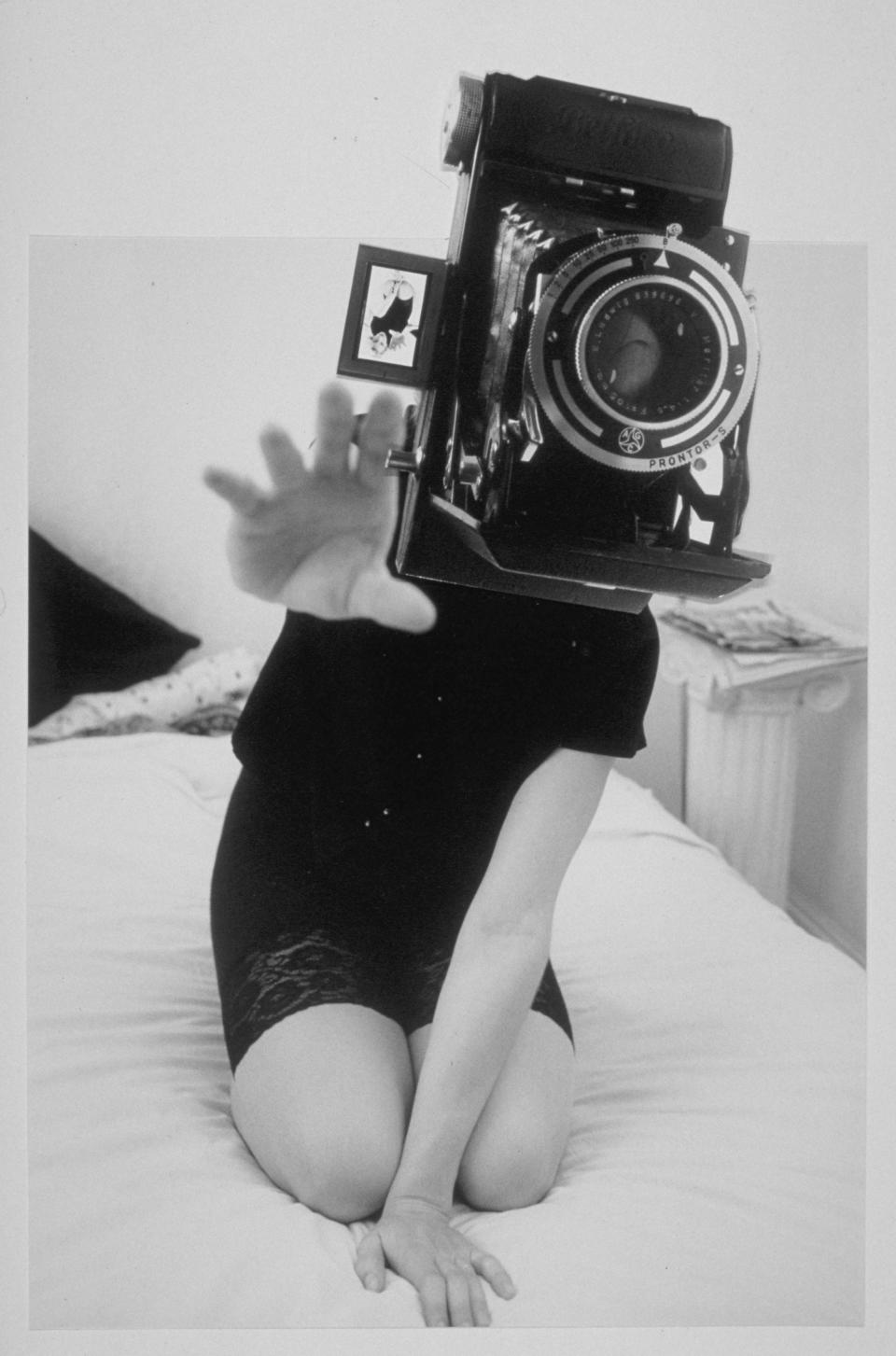

If the question of what constitutes a person seems to have particularly anxiety-inducing relevance in the age of ever-expanding AI, it’s comforting to see the work of an artist who has been grappling with that inquiry—and doing so in relation to technology—for decades. In her early Phantom Limb photographs, for instance, a woman’s body is merged with technology, a movie camera planted cartoonishly on her head.

03---Lynn Hershman Leeson Reach.jpg

But perhaps the greatest investigation of that idea takes place in Leeson’s Electronic Diaries, which greet the viewer upon entering Manual Override. Filmed between 1984 and 2019, the diaries—short films projected on a series of screens, marching across the gallery—seem a foreshadow of many things: the reality TV confessional, the vlog, the Instagram story monologue.

Manual Override - Install

But if those formats connote superficial engagement with interiority, Leeson’s videos are raw, poignant, and painful. In the first, she describes the early years of her daughter’s life, in which she would send her child to other people’s houses for a complete meal and how she would hang around in hotel lobbies to get work as a call girl—the work, she matter-of-factly reports, “became kind of like a part-time job”—and the disordered eating that took root as a means to cope with all this hardship. “Eve proved that eating is a sin for women,” she says in the film. In the series’s second film, she connects the Dracula story to childhood abuse and its dark, lifelong toll. Other films circle around themes of illness, loneliness, sexism, mortality.

In the last film of the series, making its debut at the Shed, Leeson further dissects the idea that, as she puts it, “we are the editors of our own lives,” this time turning to biomorphic dimensions. “I felt like I was being buried by my own information,” Leeson says, and a method of exercising some control is, apparently, to reduce herself to her most elemental components. As she describes in the last film, she had her films “coded” within a DNA molecule—that work is on display in the work Room #8, as an illuminated vial visible behind a locked door—and an antibody created that uses the letters of her name as the basis for the molecular structure.

As Leeson puts it in one of the films, it’s the “prison of my past I’m trying to wipe out with these films,” and the same might be said of the antibody as well—a neutralizer of toxins derived from the very toxins themselves. In this, she points to the way that technology can be used not just to catalog a life of woe. (In the last film, Leeson almost sheepishly admits that the films capture a particularly bleak vision of her history, leaving out the friendship and love that she also experienced along the way.) Technology, and the way it lets us open up and examine the poisonous baggage we carry around, can also allow us to abandon it.

Originally Appeared on Vogue