When Picasso, Chagall and Calder Collided With Fashion

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

LONDON — Fashion and art have long had an on-again, off-again relationship, and a new exhibition in London highlights a moment, just after World War II, when they were definitely on — and producing groundbreaking work.

“Styled by Design,” curated by Gray M.C.A, the fashion illustration, design and textiles gallery, highlights a colorful moment when British-based textile manufacturers worked with modern art giants to create fashion, home and decorative textiles.

More from WWD

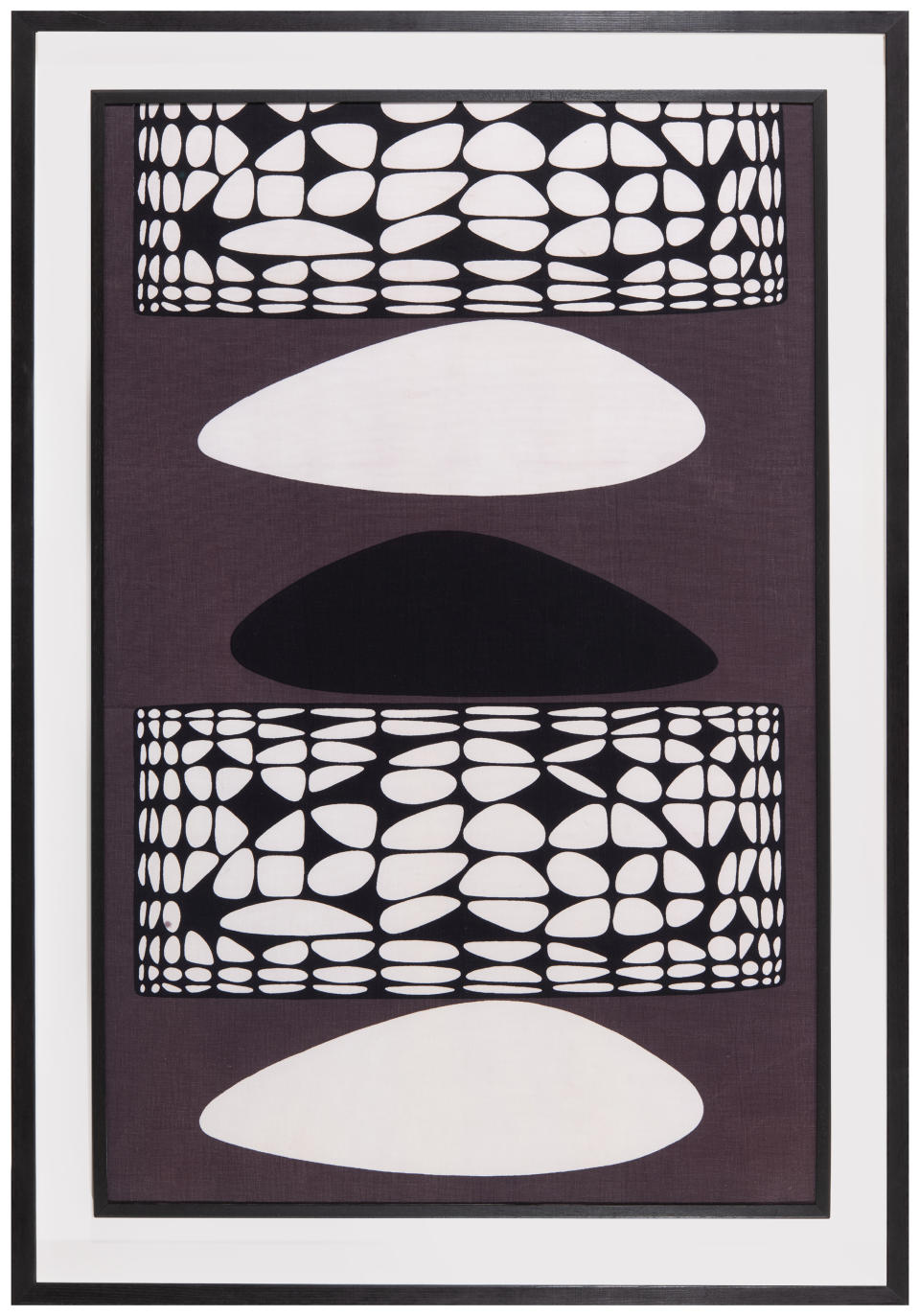

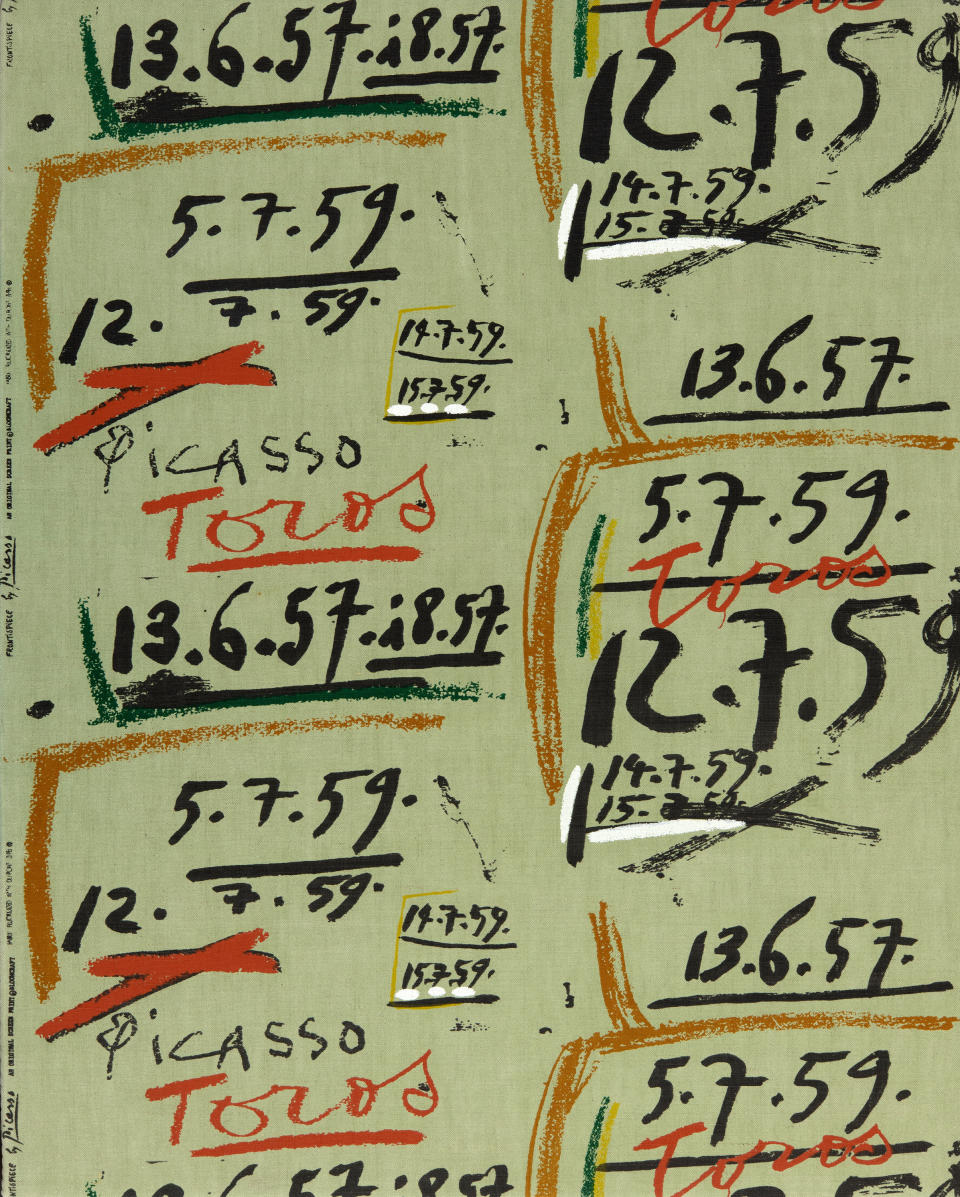

The exhibition, which features rare and limited-edition textile designs by Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and others, opens Tuesday and runs until April 30 at Cromwell Place in South Kensington.

The pioneers of the movement were Zika and Lida Ascher, a husband-and-wife team of textile experts who left their native Prague for England in 1939, shortly after Nazi Germany annexed Czechoslovakia.

Shortly after the war, Zika Ascher began brokering deals with the artists to create designs for textiles. He wanted to leave pain (and dreary aesthetics) of war behind and add a shot of color — and optimism — to people’s wardrobes. He also wanted to get the artists working again.

“This was real austerity: the artists weren’t finding the commissions and work they had before the war. The marketplace for art had evaporated. The big question was: ‘How do you get traction again?’ It was the same for fashion,” said Ashley Gray, director at Gray M.C.A.

Gray said Ascher and his contemporaries in the textile trade were eager to engage new audiences in Europe and the U.S., and they succeeded by pressing popular artists into action.

“Suddenly modern artists’ work was blossoming on the streets. Their art was being worn as clothing, or beautiful scarves. Modern art became democratized,” said Gray, adding that the show “celebrates the modernist view that ‘a good textile was the equal of a good painting.'”

In the years following the war, the Aschers developed relationships with a number of artists, giving them the freedom to create whatever they wanted. The Aschers then figured out how to make the designs work on a variety of fabrics such as cotton, rayon, silk and woven wool, and to ensure the colors and prints were just right.

The trend for tapping top artists took off, and soon Moore was designing fabrics for costumes in Hollywood films; Claire McCardell was working Picasso’s fish prints into her dresses; and top models of the time were posing in Marc Chagall’s studio, wearing his dreamy prints and warm colors.

At one point, Zika Ascher even got Lucian Freud on board to design a crêpe de Chine fabric. In the meantime, the Aschers were also supplying fabrics — artistic and otherwise — to the likes of Christian Dior, Balmain and Balenciaga.

The famous Ascher silk squares, which featured original designs by artists including Ben Nicholson, Moore, Hepworth and André Derain, made their debut at the Dorchester hotel in London. They were framed, just like paintings, and made an international splash.

After their Dorchester debut, the silk squares embarked on a world tour, with exhibitions across Europe, South Africa and the U.S. “The series became a phenomenon,” said Gray, who has spent years scouring Europe and the U.S. for the textiles that feature in the show.

“Styled by Design” is a selling exhibition with prices ranging between 1,500 pounds and 170,000 pounds.

Among the highlights is a vast 1949 Ascher screen print on linen by Moore called “Two Standing Figures”; Nicholson’s 1937 “Vertical” for Edinburgh Weavers, a home furnishings maker near Manchester, England; and Patrick Heron’s “Nude” silk scarf, drawn while Heron worked for his father, Tom Heron at Cresta Silks.

Gray said the frenzy of textile research, development — and creativity — in post-war Britain cannot be underestimated.

Ascher and his peers were not only making textiles, they were researching and developing dyes (before the war, most dyes were sourced from Germany) and experimenting with synthetic textiles.

“Machinery and mechanisms were changing quickly, and you could produce fabric economically,” said Gray, who described the 1950s as “the furnace of creativity” in Britain.

By the 1960s, that golden age of arty textiles was winding down.

A new generation of textile designers, influenced by abstract expressionist artists such as Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning, were visiting art galleries, looking at museum catalogues in color, rather than in black and white, and creating painterly designs of their own.

“The light goes off the big artists, and the innovation starts to come from the art schools,” said Gray.

And — thanks to Zandra Rhodes, Celia Birtwell and others — the relationship between art, applied art, and fashion was evolving once again.

Best of WWD