Was Picasso behind an art heist at the Louvre?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Paris, 1911 – in the dead of a September night, Pablo Picasso, still only 29 years old, is staring into the dark waters of the Seine with his friend, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Between them, on the cobblestones, is a suitcase containing stolen goods: two ancient Iberian sculpted heads, pinched from the Louvre by a shady friend in 1907 and stashed ever since in the artist’s cupboard. Terrified that the police were on to them, the pair had spent a feverish night dragging the suitcase around the city before deciding to chuck it into the river. Better safe than sorry. As foreigners, neither wished to be deported from the City of Lights.

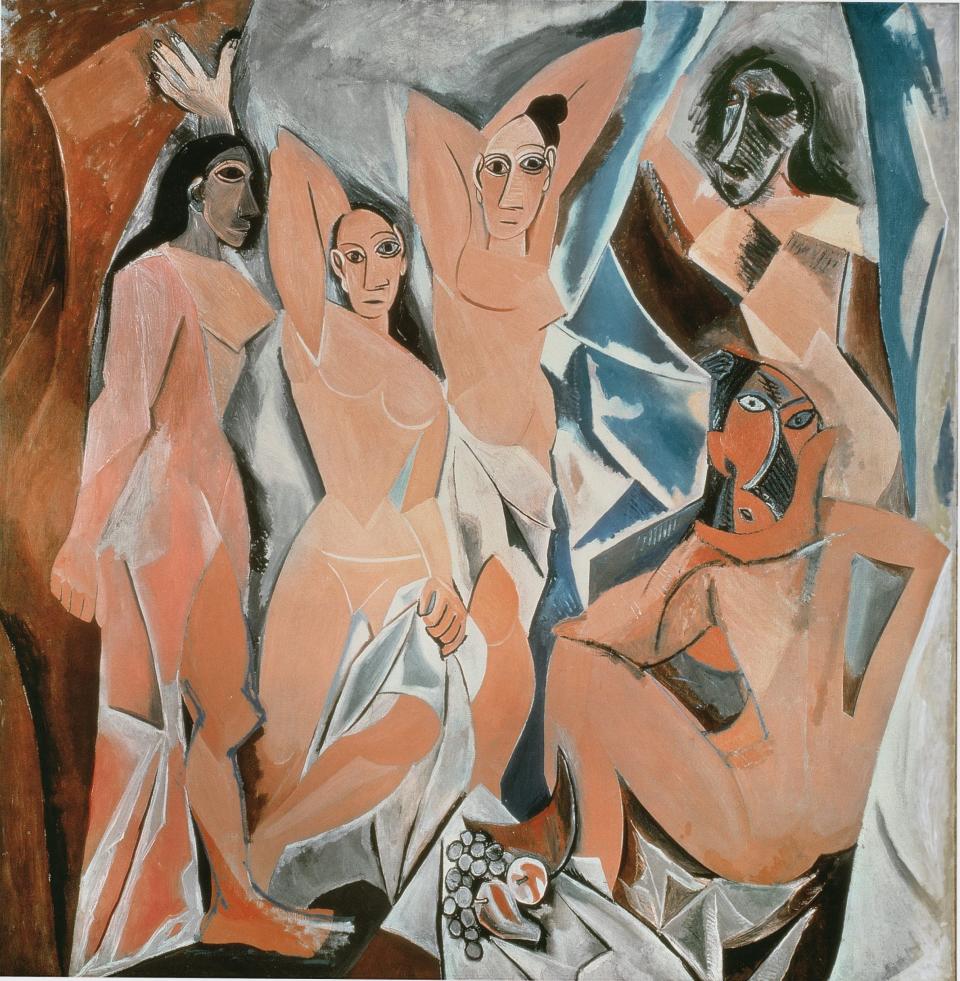

In the event, though, Picasso couldn’t do it. Who could blame him? Since at least the spring of 1906, he had been obsessed with the archaic art of the Iberians, a pre-Roman people who once occupied the south-eastern stretches of the Iberian Peninsula millennia before it became his homeland. He wanted, he told Apollinaire, to uncover the “arcane secrets” of their “ancient and barbarian art” – and the impact of those stolen heads, with their heavily rimmed eyes and prominent ears, is evident in the facial features of the two central women in his proto-Cubist breakthrough of 1907, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon). In other words, the contents of that suitcase helped Picasso invent Cubism.

Art historians have known about this Iberian connection for decades, but there has never been an exhibition specifically dedicated to the subject – until now. Next month, Picasso Ibero will open at the Renzo Piano-designed Centro Botín overlooking the Bay of Santander on Spain’s northern coast. Mounted in collaboration with the Musée national Picasso-Paris, and featuring more than 200 works, the show will run until September – by which time it is hoped that visitors from Britain will be allowed. Among the 14 Iberian masterpieces on loan from the Louvre will be the two heads once in Picasso’s possession that precipitated a frightening run-in with the law. This notorious, traumatic episode – covered at the time by the French press, who dubbed it the “affaire des statuettes” – troubled the artist for the rest of his life. It was, as a friend put it, like a fishbone forever stuck in his throat.

To understand the “affaire”, we need to go back to the late 19th century, when archaeologists in southern Spain started unearthing artefacts of a little-known ancient Mediterranean civilisation. In 1904, a few months after Picasso had settled permanently in Paris, a new Iberian room, presenting the discoveries, was unveiled at the Louvre. At the time, his art was evolving, from Blue Period to Rose. Before long, it was changing again. According to a friend, Picasso used to pace the antiquities galleries at the Louvre like a hound in search of game. “He was trying to escape from academicism, from tradition, and was looking for a new, more authentic [visual] language,” explains Cécile Godefroy, curator of Picasso Ibero. Two monumental self-portraits by Picasso from 1906 suggest that, eventually, he sniffed out the seemingly crude, coarse sculptures of the Iberian room.

The intense dark eyes in both paintings are easily recognisable. Yet, says Godefroy, in each case, the figure is also “more generic, more synthetic. The face is very sculptural, [like] the masculine heads Picasso had observed in the Louvre. Even the dominant colour is much closer to stone.” Picasso was, Godefroy explains, “looking for objectivity, trying to erase sentimentalism from portraiture.” His quest “started with Cézanne, Gauguin – and Iberian art.”

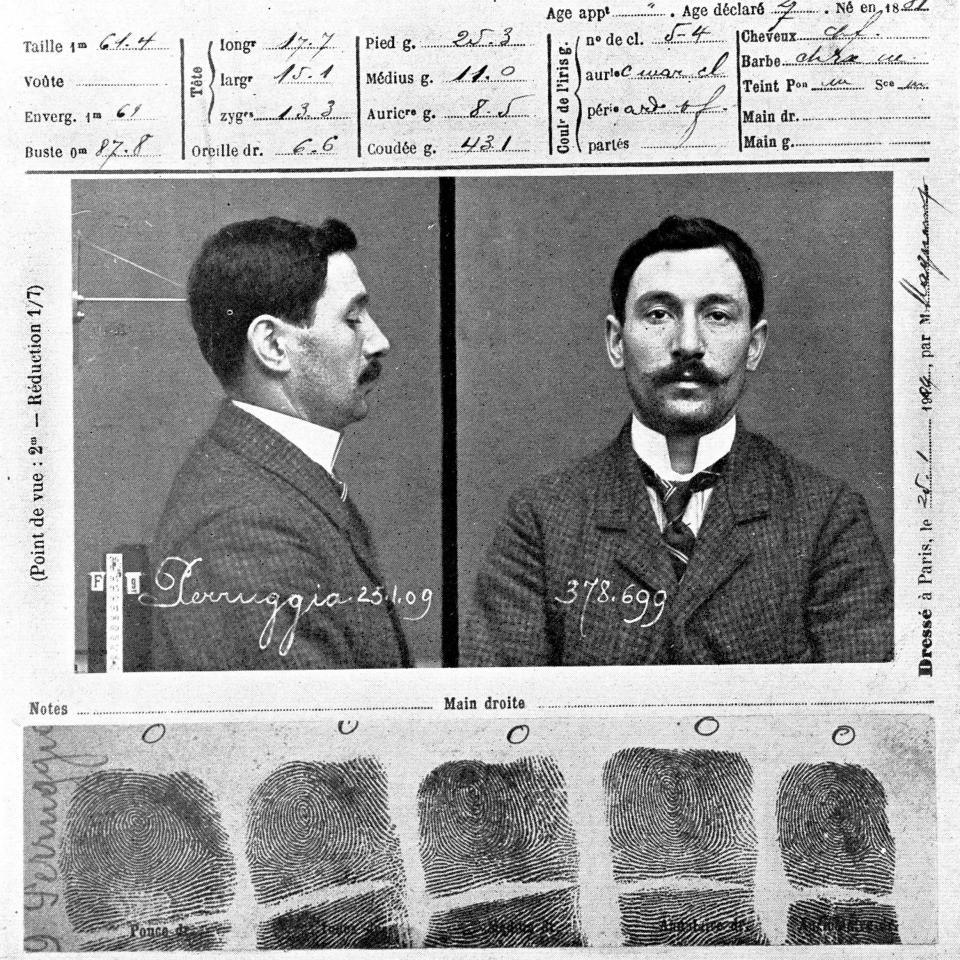

What, though, of the heist? In those days, security at the Louvre was astonishingly lax. When the guards weren’t looking, you could secrete, say, a 6kg Iberian limestone head beneath a raincoat, and wander off. Which is exactly what Honoré Joseph Géry Pieret, an itinerant Belgian rogue, and the thief at the centre of the “affaire des statuettes”, did. Described by Picasso’s biographer, John Richardson, as a “narcissistic psychopath”, Pieret had befriended Apollinaire, who was besotted with him, in 1904. He was, says Godefroy, an “eccentric” who liked to pinch objects for a dare. “I’m off to the Louvre,” he would announce, according to André Salmon, a poet in Apollinaire’s circle. “Is there anything you need?”

In March 1907, Pieret stole two of the Louvre’s Iberian sculptures, both dating from the 3rd century BC, and excavated from the religious sanctuary of Cerro de los Santos, or Hill of the Saints, at Albacete. He subsequently sold one, a yellowish-beige head of a woman with plaited hair, to Picasso. Although the artist refused to pay for the other, of a man with elongated ears, Pieret left it with him anyway. According to the artist’s mistress, Fernande Olivier, he kept the heads in a cupboard in his mice-infested digs in Montmartre.

We know they intrigued him: the preparatory sketchbooks for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon are full of elongated faces that, says Godefroy, “with their almond-shaped eyes, arched eyebrows, high foreheads, and absence of expression, are indebted to the two heads – it’s stunning.”

The obvious question, then, is: did Picasso commission Pieret to pilfer them on his behalf? Despite much research by Richardson and the Apollinaire specialist Peter Read, we’ll probably never know. However, Godefroy notes that, in the spring of 1907, Pieret was staying with Apollinaire. Perhaps he heard the artist enthusing about Iberian art and decided to nick the heads to please him. For his part, Picasso must have known the sculptures were stolen – otherwise, why squirrel them away? They remained in his wardrobe until the sensational theft from the Louvre of the Mona Lisa, on August 21 1911, made him panic.

To elicit the recovery of Leonardo’s painting, French newspapers offered rewards for information – and Pieret, who had lifted a third Iberian head earlier that year, decided to cash in. He took his latest acquisition to a Parisian journal, and sold his story for 250 francs, on condition of anonymity. The ensuing front-page article, a broadside against the Louvre’s woeful security, referred to Pieret only as “The Thief”: a Fantomas-like character who claimed to have sold an Iberian head, a few years earlier, to “a Parisian painter” for 50 francs, “which I lost that same evening in a billiard hall.”

Fearful that he and Picasso would be implicated, Apollinaire summoned the artist back from the Pyrenees, where he had been staying. In her memoirs, Fernande recalled their plan to hurl the evidence into the Seine: “After a hastily swallowed dinner and a long evening’s wait, they set out on foot around midnight with the suitcase; at two in the morning they were back, worn out and still carrying the suitcase with the statues inside.” The next morning, Apollinaire turned them in to the newspaper that had carried Pieret’s story.

Desperate to crack the Mona Lisa case, the police, tipped off about Apollinaire, locked him up for several days in La Santé prison (which, at least, inspired some poetry). Picasso, too, ended up in a courtroom, where he trembled and wept hysterically, and supposedly blurted, gesturing at Apollinaire: “I have never seen this man.” Somehow, the case was thrown out, and Picasso got off scot-free. Two years later, the Mona Lisa – stolen, it turned out, by an Italian who had worked at the Louvre – resurfaced in Florence.

By then, Iberian art had lost its hold over Picasso. At least, that’s the traditional view – but Godefroy detects an important Iberian “renaissance” in his imagination during the early 1930s, when he was working in secret at his recently acquired 18th-century chateau at Boisgeloup in Normandy. Was this the moment a mysterious collection of 95 Iberian artefacts – mostly small bronze votive statuettes, discovered among Picasso’s belongings at his death – came into the artist’s possession?

For decades, Picasso kept quiet about his passion for Iberian art. Eventually, though, he told a confidant: “Do you remember that affair I was mixed up in, when Apollinaire stole some statuettes from the Louvre? […] Well, if you look at the ears of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, you’ll recognise the ears of those sculptures!”

Had Picasso misremembered – or was Apollinaire, not Pieret, the culprit after all? Or maybe, still worried that he could get in trouble, the artist, whom Apollinaire once described in a letter as “completely unscrupulous”, was dodging any blame. Who would challenge his version of events? Apollinaire had died years earlier, in 1918.

But Godefroy says: “I am not so sure. I don’t think he pointed his finger at Apollinaire to duck responsibility. Like many artists, Picasso didn’t talk a lot about his sources. Yet, throughout his life, he was fascinated by ancient Mediterranean forms and themes: Cycladic idols, Etruscan bronzes, Cypriot pottery, prehistoric goddesses. Iberian art belongs to this formal and conceptual repertoire – and acted even more strongly on Picasso’s imagination by taking him back to his Spanish and Andalucian origins. He was convinced it was as contemporary as modern art.”

Picasso Ibero is at Santander’s Centro Botín from May 1-Sept 12; centrobotin.org