When Peter Met Eric: An O.G. Love Story

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

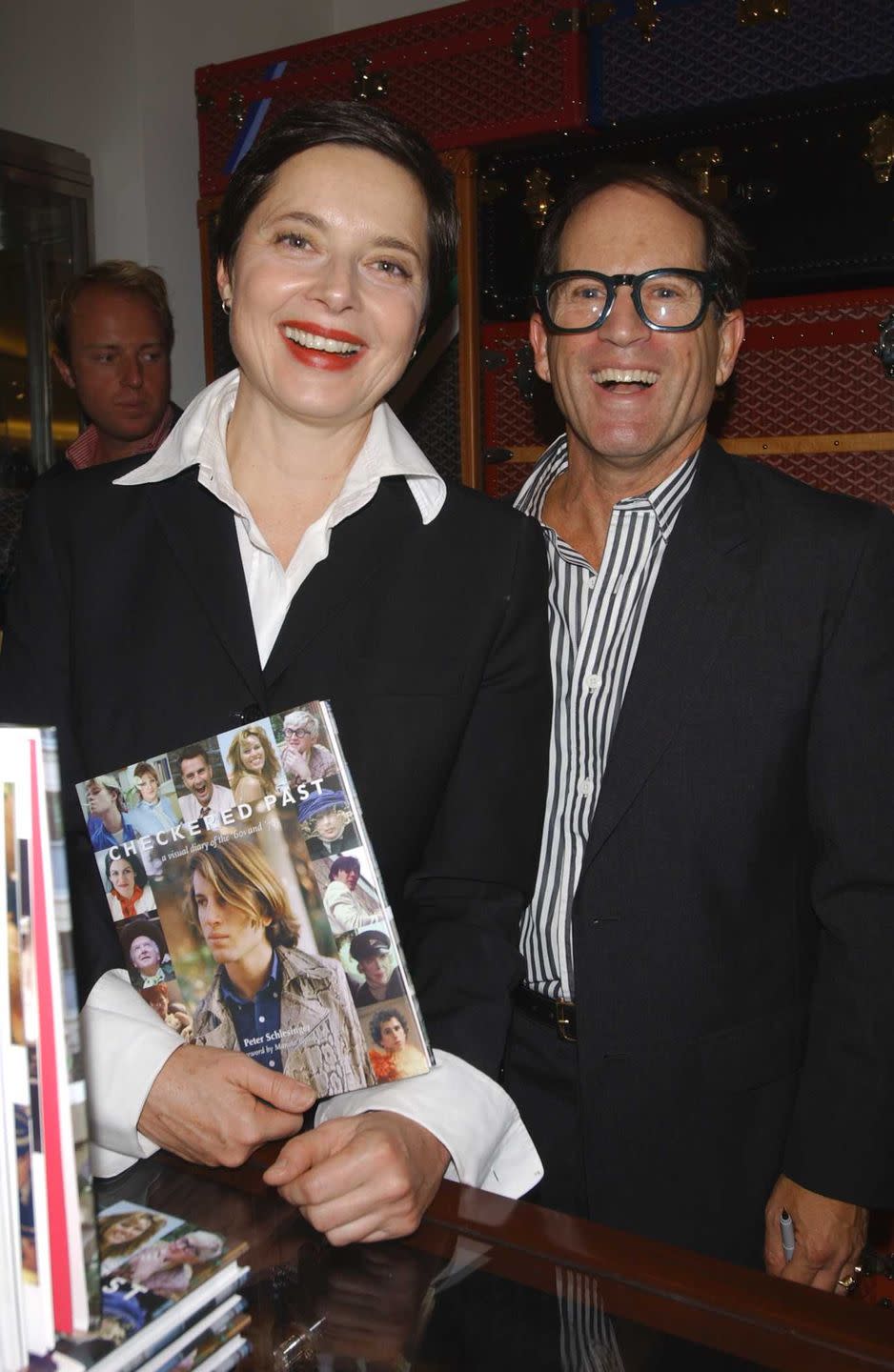

The photographer Eric Boman has died. T&C paid tribute to his 51-year relationship with the artist Peter Schlesinger earlier this year. That story, below.

All romances have improbable origin stories, but few begin with such a glamorous set of incidents as the ones that brought together artists Peter Schlesinger and Eric Boman.

Schlesinger (pictured above in his ceramic studio in New York), born in 1948 in over-sunny Los Angeles to an insurance agent and a social worker, had always aimed for a life in the arts. It was while studying painting at UCLA at 18 that he met his future boyfriend David Hockney, and after graduation Schlesinger moved with the Pop icon to London to attend art school at the Slade. Meanwhile, Boman, no less a born bohemian (although his Swedish paternal line traces back through 350 years of Lutheran ministers), made his way to London in 1966 to study graphic design at the Royal College of Art.

Both exceptionally handsome and talented young men were up to their necks in a sophisticated milieu of bons vivants and rough-and-tumble creative gypsies that came to define the early 1970s London scene. The two had never met until the evening of March 16, 1971—Boman remembers the date. “Attention: a long, name-droppy story,” he warns with his signature sly wit.

According to Boman, Paloma Picasso and Fred Hughes (the business mastermind behind Andy Warhol) happened to be in town for the premiere of Luchino Visconti’s Death in Venice. They decided to invite friends to dinner at Mr. Chow in Knightsbridge after the screening. “Paloma asked Manolo Blahnik and me, and Fred asked David Hockney and Peter Schlesinger,” Boman recalls. “David was not interested, so this adorable boy turned up at our table in a camel hair Ossie Clark coat. Fred had not realized the movie was so long, and we got a good start (and many screwdrivers) before they arrived.” Schlesinger remembers it as love at first sight, and they’ve been together ever since—which is now 51 years.

In those London days Schlesinger lived in Notting Hill and Boman in Battersea. “It was a very long commute between us,” Schlesinger says, “by buses or bicycle.” His primary medium then was painting, but he did carry around a Pentax camera, shooting friends and familiars. Many of Schlesinger’s candid, painterly snapshots have come to define the stylish, carefree spirit of that era: Warhol and Rex Reed in the back of a taxi in Monaco, 1974; Amanda Lear tossing her hair through the air on the photographer’s London terrace in 1973; Robert Mapplethorpe or Peter Berlin cruising the daylights out of 1970s Paris. There are also plenty of photos of a boyish, towheaded Swede hanging out on beaches and in parks—Schlesinger’s love for his subject is palpable in these shots, as the lens lingers on Boman’s beauty and mysterious gaze.

As it turned out, Boman too would end up a celebrated photographer. In 1972, on a lark, he borrowed Schlesinger’s camera to take his first photographs for Harpers & Queen after being assigned an illustration commission by the magazine (an editor there named Anna Wintour took a shine to him). Soon afterward Boman was off to India—“I was cheap, had never heard of assistants”—for his first Vogue shoot, which featured Grace Coddington, who also styled it. Boman would make a bold career out of fashion editorials that pulsed with the excitement of an electric current throughout the 1970s and ’80s; some of his most memorable shots graced album covers, specifically for Roxy Music and Bryan Ferry.

While Schlesinger’s and Boman’s lives merged, their styles and creative approaches remained distinctive. “We admired the same photographers but used it differently,” Boman says. As Schlesinger puts it, “We’re both artists and have that bond in common, but our careers weren’t competitive because we didn’t do the same thing. In terms of photography, Eric is very methodical and likes setups. I just snap pictures, and he doesn’t understand that!”

In 1978 the couple moved to New York, driven out of London partly by its skyrocketing expense, and a year later they settled in the area where the Flatiron District meets Chelsea, in a 10th-floor loft that had once been a girdle factory, with windows facing north and south. At that time the neighborhood wasn’t even residentially zoned, much less dotted with stores, and both men recall friends shaking their heads at the terra incognita of West 20th Street. But the expanse of raw space allowed them to build separate studios. As Schlesinger says, it was before the days of the professional photography studio, and Boman, like many photographers, would do shoots out of the house. Schlesinger’s painting studio was originally accessible only through their bedroom, “which,” he admits, “made it a little bizarre when someone would come for a studio visit.”

More than 40 years later the couple still occupy the loft, with their 11-year-old wirehaired fox terrier Oscar. It’s furnished with “midcentury international flea market finds,” as Boman puts it, including pieces by Edward Wormley, Piero Fornasetti, and Gio Ponti, along with a few paintings by Schlesinger. In 1982 the couple purchased a mid-19th-century Greek Revival house near the beaches of Bellport, on Long Island, and in late spring they make their annual migration out east for the summer. Schlesinger has become an expert gardener, and Boman often uses homegrown ingredients for his own spin on Scandinavian-inflected dishes. For a while he was even pondering authoring a cookbook with his own still lifes. He’s currently at work on a book of his black-and-white still lifes from the late ’80s forward, which he calls “portraits of objects.”

By the mid-1980s Schlesinger had grown disenchanted with painting. “I never really enjoyed the process of painting,” he says. “I wanted to find something I did enjoy.” In 1987 that urge led him to visit a potter friend’s studio, where the erstwhile painter instantly became enraptured with the elemental tactility of clay. So began the artist’s third chapter as a master ceramist. Schlesinger converted his studios in both the city and the country, and in the latter, thanks to a grant, installed a gas-fire kiln that allowed him to work on a larger scale and with a more varied palette of glazes. For the past 35 years his ceramic works have included vessels, figures (a series of vignettes of male nudes and of allegorical scenes), and organic forms, like agave leaves. “It’s the oldest art form,” he says, “and you can make so many different sculptures by going in different directions.”

In January Schlesinger opened a solo exhibition at the David Lewis Gallery in New York. While it isn’t his first public showing, it represented his debut, at age 73, as a ceramist at a leading contemporary gallery. The exhibition mixed a few of Schlesinger’s early pieces with recent works: a behemoth hourglass vessel patterned in a harlequin checkerboard, an urn tattooed with playful swirls, a vase striped with a hypnotic free-flowing line of blue and black. Each piece seemed to be a wild personality gathered in a room for a party, with thrilling conversations floating between them.

In any period there are those who make the scene and those who record it. Every so often, through art, there are those who do both, like Schlesinger and Boman, for five decades and counting.

This story appears in the March 2022 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like