People Talk About the “ADHD Tax.” For Me, It’s Literal.

“This looks scary,” I said as I handed Kyle a piece of mail from the Missouri Department of Civil Process. “I bet it’s a jury summons.”

As someone with a history of accounts going into collections, I was relieved the foreboding envelope wasn’t addressed to me for a change and proceeded to brag to my husband that I’d only been called for jury duty one time, in the early aughts.

“It was, like, six months after I moved to Brooklyn,” I chirped. “I lost the paper and then I never heard from them again!”

Except I probably did hear from them again and I just didn’t know it because I don’t open my mail—which, it turns out, was the reason the government was now sending scary notices to my husband. Well, that and he was the one with a real job, so he had actual wages that could be garnished to settle my state tax debt from 2017.

The letter that was very much not a jury summons said that with interest and penalties, I owed the Missouri Department of Revenue $3,769.03. Plus whatever I owed for 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021, which I hadn’t yet filed though the April 18, 2022, deadline was quickly approaching.

For the record, I’m a person who believes in paying taxes—so much so that when boomers hurl “socialist” at me as an insult on Facebook, I enthusiastically click the heart reaction. I just happen to be really bad at filing my taxes. And when I finally get myself motivated or terrified enough to do that part (which is technically just locating and scanning a million different 1099s and receipts to send to my tax guy), I never have enough money in my checking account to pay what I owe.

Because I’ve always been bad at paperwork and money management—and very aware of my shortcomings in this particular area—years ago I set up auto payments so I could attempt to stay somewhat on top of my tax debts without having to think much about it. Once a month my bank would auto-magically mail a $250 check to the IRS and, I thought, a $100 check to the state of Missouri.

“It’s enough to keep me from going to debtors’ jail,” I occasionally joked to Kyle, who never laughed when I said it.

Except I apparently never finished setting up the Missouri payment (and never noticed it wasn’t processing), so as far as somebody behind a desk in Jefferson City was concerned, I was not only behind on my taxes, I was making zero effort to get caught up. I also wasn’t responding to any of their correspondence, so they were left with no choice but to garnish my husband’s wages. And it was all my fault.

Spend enough time in ADHD forums or even just a few minutes scrolling #ADHD TikTok and you’ll see the term “ADHD tax” pop up with some regularity. It’s a made-up term for a very real problem: the extra costs incurred as a consequence of executive dysfunction. In addition to penalties, late fees, and garnished wages, ADHD tax might mean paying an impound lot to get your car back because you thought it was Tuesday but really it was Wednesday and you parked on the wrong side of the street. It’s spending half your paycheck on fresh vegetables only to forget you bought them—until you smell them rotting in the bottom of the fridge. It’s having to take an unpaid day off of work to get a new driver’s license and debit cards because you lost your wallet yet again. My personal ADHD tax liability also includes a $4,000 emergency plumbing repair from the time a storm blew out our 100-year-old terracotta water line two days after I let the coverage policy expire. Weeks earlier, I’d told Kyle I’d take care of it, then the renewal form got buried on my desk (to be fair to me, I also had a newborn and my car had recently been totaled in a hit-and-run, but still). We didn’t have a cool four grand laying around, so it went on a credit card. Cha-ching, cha-ching, cha-ching.

Beyond the more obvious financial losses, ADHD tax can also be used to describe opportunity costs like getting denied for a mortgage or an apartment as a result of a low credit score, missing your favorite band when they come to town because you put the wrong date for the ticket presale in your calendar, and losing hours of your life to phone calls with billing departments. Those scenarios almost always have their own financial consequences, too: paying double for a concert ticket because you have to buy it from a scalper, shelling out for a motel or rental car or second plane seat because you missed your flight, and even knowingly signing the contract on a predatory loan or lease because, after all of your missteps, it’s your only option.

But the worst part isn’t the money (though that’s hugely stressful); it’s the shame.

When I pictured my life at 40, I never imagined I’d still be living paycheck to paycheck. Avoiding calls from unknown numbers because there might be a debt collector on the other end. Panicking when a freelance check is late. Discussing with my husband whether to pay the day care bill or the electric bill this week, then fighting over paper towels because no matter how broke we are, it’s never acceptable to buy patterned paper towels, Kyle!

And because I’m a seemingly successful person who shouldn’t be in this precarious financial situation at this ripe middle age, I go deeper into the hole to make it look like I have my shit together. Rather than admit to anyone I’m broke, I’ll gladly bust out a high-interest credit card for a friend’s birthday dinner. Also on that card? Plane tickets and hotel rooms for relatives’ weddings and funerals, a day care bill here, a tank of gas there, and when times are really tough, plain white paper towels. Because at this particular junction, a 19 percent APR is preferable to letting the world see how much of a financial failure I still am—though I have a family, a job, and a house.

The house, by the way, was only possible because not long after we got married, Kyle received a small inheritance from a great-uncle. It wasn’t life-changing money, but it allowed us to pay off our wedding debt and put a modest down payment on a modest Midwestern bungalow. We also had to use a little to take care of one of my collections accounts that would have prevented us from getting approved for a mortgage.

“Just because you’re poor doesn’t mean you have to look poor” is a thing my mom used to say. And it’s probably one of the many reasons I never stood a chance financially.

Even without ADHD, the economic cards were stacked against me. I was a free-lunch kid who grew up in subsidized housing. My parents divorced when I was 3, and when my mom got the child support check every other week, she would treat herself. I’m not saying she never bought food, because she usually did, but purses and shoes were her things. Making sure her kids always had what they needed? Not so much. She was even less attentive to our needs once we were old enough to kinda sorta take care of ourselves. I started working when I was 14 (as soon as I was legally allowed) so I could buy trendy Lucky jeans and Doc Martens that would make me look “not poor.” I also had to purchase things like deodorant, shampoo, makeup, and hopefully a car to get back and forth to my job since my mom was often nowhere to be found when I needed a ride.

Fueled by desperation for a better life and a few small scholarships and Pell Grants, I made my way to college in New York. Where I got my first tax hit.

By my junior year of college, I was tired of scrambling for the documentation I needed to fill out my FAFSA, the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (without which it was impossible to get any sort of loan or grant), so I made a big deal of filing my taxes on time. It was a huge pain in the ass because I had, like, four different jobs and no money to hire a preparer, but without financial aid, I wouldn’t be able to get enough credits to graduate. And all my life I’d been told that once I had a college degree, I’d be able to have a successful career and pay back the loans (I was also promised 2.5 children, flying cars, and world peace). So I gladly signed my name on those promissory notes full of legally binding fine print about compound interest because 1) I had no clue what compound interest was, and 2) it meant I could stay in school.

But I couldn’t get a loan without a FAFSA and I couldn’t complete the FAFSA until I’d filed my tax return.

When my timely tax return was rejected in an equally timely manner, I assumed I’d made a mistake; I’m terrible at numbers and I’ve never been one to pay close attention to instructions. A financial aid counselor helped me figure out that (on the advice of some guy from her church, I later learned) my mom had claimed me as a dependent so she could get a tax credit even though I was supporting myself in New York City and hadn’t lived under her roof or received any help from her since I was 16. And because she filed earlier than I did, and had already received (and likely cashed) her refund check, I would never see the paltry refund I was planning to use on textbooks. To make matters worse, I had to refile my taxes.

As much as I would like to blame all of my money problems on my mom’s low-level tax fraud, it was really more of a kick-me-when-I-was-down situation because I was already in the red—and in the process of developing my own terrible financial habits.

Scraping together funds each semester was a part-time job in itself, so other bills got shoved into my Drawer of Doom because looking at them made me want to vomit or cry or both. I had every intention of getting up to date with everything when I was able (my con woman days started and ended with Columbia House), but I was never able. As the drawer filled with more threatening letters and collection notices, I became filled with dread and shame, so I transferred the papers into a plastic tub, which went into a closet, and it made me feel so much better about my life (albeit temporarily).

Clearly, my filing system had some major flaws, or maybe it was just one big flaw. I honestly believed I was putting things away “for later,” but once something was no longer out in the open, it might as well have been gone forever.

About once a year, I’d have a freak-out about money and decide I was really going to get my shit together (“for good this time!”) and I’d spend weeks making spreadsheets and calling collection agencies to set up payment plans. It was a dicey stopgap, and I was continuously robbing Peter to pay Paul, but I was trying. One late freelance check or impulsive purchase and the whole system would implode—which it always did—and I’d go back to shoving collection notices into the Drawer of Doom.

In spite of my debilitating debt and major cash flow problems, I could not stop shopping. When I’d get an unexpectedly large tip at the cocktail bar where I worked or deposit a paycheck from one of my other jobs, I was momentarily able to experience what it felt like to have money, even if a profit and loss sheet would have proved otherwise. Having money and giving myself permission to spend it felt so good—the complete opposite of most days, which were filled with stress from being beyond broke in one of the most expensive cities in the world. It’s not like I was buying $3,000 bags (I wasn’t even buying $300 bags), but if I had a little cash, I would not hesitate to treat myself to a fancy coffee or funky necklace from Urban Outfitters. Sometimes it meant I could go out to a nice dinner with a friend and pretend I was a real adult. I felt like such a high roller whenever I didn’t have to do math in my head before ordering. Spending money like I had it to spend gave me such a rush that it was easy for me to compartmentalize the idea of my money, even when it meant I might not be able to buy groceries the next day.

Less frequent but perhaps more dangerous were the times I fell in love with a particular sweatshirt or slouchy purse (again, we’re not talking Birkin bags here). Once I became fixated on something, there was no way to stop myself from buying it—which could result in me overdrawing my bank account on purpose. For some reason, Bank of America allowed me a $200 overdraft limit and I’m certain that reason was their $35 overdraft fees.

If I had it to do over again, I’d tack all my unpaid bills up on the wall and highlight the balances in neon yellow so I’d be forced to face them every damn day. In addition to a much-needed physical reminder of my myriad debts, the potential shame factor of friends and OkCupid dates seeing my financial messiness might have sent me down a different road. Instead, I stayed on the fiscally unstable path—never able to catch up no matter how many articles I wrote or cocktail shifts I worked. I just got used to putting out fires as a means of survival.

Because I always worked at least a few jobs, it took me six years to finish college. When I left, it was with $50,000 in student loan debt. I was supposed to start paying it back six months after graduation, but at that point, I was still so broke that I was granted a financial hardship forbearance. I didn’t entirely understand what that entailed, but I was told I wouldn’t have to make payments for a while, which at least meant I could continue to cover rent—while that interest would continue to compound. I ended up consolidating my loans with a graduated repayment plan, and for more than a decade, I made monthly payments between $300 and $600 (auto-drafted, so I wouldn’t forget). The bright side? I have a better understanding of compound interest. After paying tens of thousands of dollars toward what I originally borrowed, my balance currently hovers around $75,000. That’s $25,000 more than I owed when I graduated in 2006.

So now I’m one of those entitled (elder) millennials with a fancy East Coast liberal arts education they complain about on Fox News. And I will probably never get to retire.

My ADHD diagnosis helped me understand how I got here and allowed me to let go of some (but not all) of the shame. And after years of unpredictable and unreliable income as a freelancer, I have a good job that I love doing (for now, anyway), but I’m in such a deep hole that most of what I earn goes toward debt. I’m still really bad at managing my money and filing my taxes. And when I’m feeling overwhelmed and stressed about finances, I still shove scary letters into a drawer so I can relax enough to enjoy dinner with my family—which means there’s probably another big issue on the horizon.

I have stopped putting unnecessary shit on credit cards, though. Mostly because of the most recent scary letter to land in my mailbox. It was from the IRS’s collection agency—addressed to me this time—letting me know I owed the federal government $50,000. Nearly half of it is penalties and interest.

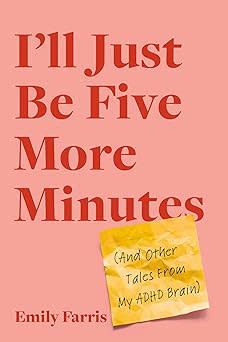

Excerpted from I’ll Just Be Five More Minutes: And Other Tales From My ADHD Brain by Emily Farris. Copyright © 2024. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.