People Say Gullah Geechee Culture is Disappearing. BJ Dennis Says They're Wrong

BJ Dennis does not want this story to be about him. He tells me this approximately 27 times over three days, as we barrel down the swampy coasts of South Carolina and Georgia in a boiled-crawfish-red Hyundai Santa Fe with the A/C cranked to five. He tells me a few more times in our follow-up calls, and again over text message. “This ain’t about me.” That’s the refrain. “This is cool and all, but it ain’t about me.”

At first I’m tempted to read it as a classic humblebrag. Lots of chefs say things like this; lots of actors and musicians and other famous types do too. But as is the nature of humble-braggarts, most don’t actually mean it.

BJ Dennis means it.

I first heard about Benjamin “BJ” Dennis IV because of a pop-up he started back in 2012 at Butcher & Bee, a Charleston café. Seeking to dispel the idea that African American food consists solely of fried chicken and mac ’n’ cheese, the chef built his menus around what his Gullah Geechee ancestors ate: fresh-caught seafood, local produce, heritage grains. The media took notice. But instead of opening a restaurant or hiring a PR firm or competing on a cooking show, Dennis, who is now 40, worked as a caterer and private chef so he could keep hosting pop-ups and collaborations all over the city, then all over the country.

His pop-ups were not just about serving delicious food but also about educating diners, and he emerged as a de facto ambassador for the Gullah community: a farmer, a scholar, and a self-taught historian, just as adept at growing heirloom produce and tracing transnational foodways as he was at cooking ginger-laced pots of gumbo studded with creek shrimp. He got written up in the New York Times for rediscovering a rare African hill rice—thought to be lost forever—in a remote field in Trinidad. He taught Anthony Bourdain about Gullah food in the Charleston episode of Parts Unknown. About how the enslaved brought with them from Africa so many of the crops now considered Southern staples: peanuts, watermelon, okra, sorghum, countless varieties of rice. How their farming skills formed the backbone of not just the South’s economy but of the Low Country cuisine associated with coastal South Carolina and Georgia. How gumbo, Hoppin’ John, even shrimp and grits can be traced back to African dishes, re-created by enslaved people in plantation kitchens.

The descendants of these people, known as the Gullah Geechee, remain here on the Sea Islands and coastal plains of the American South, their longtime geographic isolation a retainer for their distinctly West African identity, including a Creole language that’s still spoken today. Dennis himself speaks Gullah, a lilting amalgamation of English and African dialects he breaks into when excited. He incorporates aspects of it on social media, interviewing elders and captioning photos for his Instagram followers: “Dem boi say e fool up wit dat one pot mux!”

Born in Charleston and raised in a squat brick ranch-style house with a basketball hoop next to the garage, Dennis grew up Gullah without thinking about it. He learned early how to pick vegetables from his grandfather’s garden and crack the crabs in his mom’s seafood gumbo without breaking a tooth. He wanted to be a video game designer but flunked out of the College of Charleston his freshman year and instead got a job washing dishes at Hyman’s Seafood. He worked his way up the line, earned a culinary degree from a local community college, bounced around some popular downtown restaurants. Then he spent four years cooking in the Caribbean—a turning point that would come to define the rest of his career.

“St. Thomas taught me to be unapologetic about black culture,” Dennis says. Seeing statues of black leaders and hearing actual Creole on TV stirred something inside him. Maybe he could use what he knew—food—to bring this sense of cultural celebration back to Charleston. To shine a light on his own community.

Doing so would mean challenging the contemporary narrative of Charleston’s food scene, which for the past decade has centered on the work of white chefs like Sean Brock at Husk and Mike Lata at FIG. National media (Bourdain included) heralded these chefs for their use of heirloom crops and traditional techniques while relegating decades-old Gullah mainstays like Martha Lou’s Kitchen and My Three Sons to the background, context-builders rather than the main event. But then here was Dennis, a chef with a foot in both worlds, a bridge between the insular Gullah community and the downtown restaurant scene. Here was a chef who could not only acknowledge the Gullah Geechee origins of his dishes, but make those origins—and their present-day implications—his focus.

“I wanted to help the next generation of Gullah Geechee chefs get their just due,” Dennis says, “to walk in the door and not get lowballed.”

Michael W. Twitty, the author and culinary historian, has been following Dennis from the start. “He is it,” Twitty says. “But the thing about it is, he’s not trying to be it. He’s trying to raise a whole generation of people to pick this mantle up. We don’t want to be icons; we want to be griots.”

Griot is a word I have to look up, but when I do, it all makes sense: “a West African historian, storyteller, praise singer, poet, or musician...sometimes called a bard.”

Edisto Island is just an hour from Charleston, separated from the mainland by a few slender waterways, but crossing over to it feels like stepping back in time. A man sells melons out of a truck parked beside the road. Mossy oaks hang low, forming living tunnels of green and gray. “Most of the Sea Islands look like this,” Dennis says. “Funny enough, this is how West Africa looks too. When [enslaved people] stepped off here, they thought it was a cruel joke.”

We’re driving through the heart of the 425-mile Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor on a mission, or rather, two distinct but parallel missions: mine, to write a profile of BJ Dennis. His, to turn my profile into something else entirely. Which is why asking him questions about himself falls on the difficulty scale somewhere close to herding cats.

As he says, this isn’t about him. It’s about Gullah culture. People have said it’s disappearing, but that’s just because they don’t know where to look: the no-frills roadside restaurants, the home kitchens, the family farms that dot the Low Country’s sun-soaked archipelago. To understand what it means to be Gullah (which is, of course, tantamount to understanding Dennis himself), we must leave Charleston altogether, go to Edisto and St. Helena in South Carolina, and St. Simons Island, Savannah, and Brunswick in Georgia. We must meet the people who live this culture every day, taste the pots of gumbo and greens their families have been cooking in obscurity for generations.

“Too many chefs act like they’re the first to do X, Y, Z,” Dennis says, “but everything comes from a place. People were doing it before it was glamorous.”

Ms. Emily Meggett is one such person, and her little yellow house is one of the first stops on our trip. At 86, she’s Edisto Island’s grand matriarch, which is to say everybody’s grandma, though she has 10 children, 23 grandchildren, 35 great-grandchildren, and three great-great-grandchildren (not to mention 21 cats) of her own. She still cooks for 100-person weddings and funerals, grows okra in her backyard, and never lets anybody leave without something to eat. On her back porch a plastic jug of homemade blueberry wine has been fermenting for nearly a year. “Grab a pillowcase, BJ,” she says, “let’s strain it.” We watch her tip sugar into the bucket of deep purple liquid as she reminisces about the old days, when things were slower, less crowded, more connected. She sets out plastic cups of the sweet but kicky wine alongside crackers with cream cheese and homemade pepper jelly the color of Christmas. “People don’t treat you warm like this anymore,” she says.

It takes an hour and a half to zigzag from Edisto to St. Helena, though the two islands are technically less than 20 miles apart. “If we had a boat it’d be faster,” says Dennis, whose great-grandfather was a ferry driver, “but that life is over now.” Today most of the docks are private, the vessels recreational. It’s a different world, but St. Helena still feels like an enclave. Home to one of the country’s first schools for the formerly enslaved, today an African American cultural institution called the Penn Center, the island was a safe haven from the KKK during the civil rights era. Here is where Martin Luther King Jr. worked on “I Have a Dream.”

Here too is where we meet Jackie Frazier, the owner of Barefoot Farms, manning tables laden with candy-sweet strawberries and plump tomatoes under a hand-painted sign. Three years in a row, his entire crop got wiped out by hurricanes, yet here he remains, bare toes sinking into the soft dirt just like his father’s before him and his grandfather’s before that. We wend our way through rows of melons and collard greens to a converted trailer out back lined with 1,500 quails cooing quietly in their cages.

“You still on that quail egg diet?” Dennis asks.

“Sure am.” Three raw eggs every morning and night, Frazier says, will cure whatever ails you: diabetes, hypertension, arthritis. But they won’t make your children—his are all grown— take over the family business. “It will end with me,” he says. “Nobody wants to farm anymore. You can make a living a whole lot easier doing something else.”

Of course, Dennis points out, kids not wanting to take up their parents’ professions isn’t a problem unique to the Gullah Geechee. But the culture’s centuries-old refusal to assimilate is what’s kept it strong. That’s why educating Gullah youth about their roots and reinstating a sense of pride in their identity is so crucial. Failing that, Gullah culture could disappear.

That’s also why people like Bill Green are so inspiring to Dennis. We meet Green over plates of fried shark and red rice at his restaurant, Gullah Grub, in a white clapboard house. A farmer, fisherman, and huntsman, Green used to have his own cooking show on the local public access channel. “When I was a kid we’d watch him actin’ stupid, cooking dishes we eat,” Dennis recalls. “He was a living legend for us. Unapologetic Geechee.” Today Gullah Grub is not only a restaurant but a training center where Green and his wife, Sara, show local middle schoolers how to cook a simple pot of rice, how to fish, how to grow vegetables. “You’ve got to teach it,” Green says, “because when you leave, you ain’t carrying nothing with you.”

Now 72, Green sees Dennis as a protégé of sorts, and the younger chef gives the love right back: “For Bill to say he’s proud of what I’m doing is bigger than any James Beard Award. This is my award. Sitting here with him.”

As our road trip unfolds, there are patterns I start to notice. Some are distressing, like how the region’s growing influx of tourists, and the property taxes that have ballooned in their wake, are pushing the Gullah off their land. On St. Simons Island in Georgia, once home to a robust community of emancipated African Americans, the black population is down to less than 3 percent, with more than a quarter of the housing units occupied only seasonally. Gullah landmarks—like Igbo Landing, where tribespeople captured from modern-day Nigeria overtook their slave ship, then walked together into the murky waters of Dunbar Creek to avoid the fate they knew was in store—are privately owned and bear no official historical marker. We drive past a cemetery for the enslaved that’s now owned by a golf course.

But I also notice encouraging things, like how nearly every Gullah home we visit has a vegetable garden instead of the typical suburban lawn. And how each visit, Dennis slips back to the car and returns with a canvas bag full of seeds to share. He knows by sight what each unlabeled ziplock and glass vial contains: Sapelo Island okra; Sea Island red peas; orca beans, so named because they look like tiny killer whales. This one came from a farmer in Benin; that one grows well in partial sun.

Today this kind of heirloom produce has become rare, expensive, often relegated to the world of upscale restaurants—an irony Michael Twitty wrote about on his blog, Afroculinaria: “Our story has been used to raise the price point of many menus so much so that the descendants of the enslaved cannot afford to enjoy and appreciate the very edible heritage that was nourished by their Ancestors’ skills, knowledge, and blood.”

That’s why community seed sharing is so important, Twitty tells me: “It’s about restoration.” By passing down the same sustenance his ancestors carried with them on the slave ships from Africa, Dennis is able to not only anchor a people to their past, but bring back the kind of self-sufficiency that’s always existed in this community. It’s a small and simple act, but it’s also a revolution.

Seeds in tow, we make our way to Savannah to meet Gina Capers-Willis, who runs the catering company What’s Gina Cooking. When we arrive, her mother, Ella, is seated at the kitchen table, critiquing her daughter’s dishes and regaling us with tales: how she learned to make moonshine at 13, how she found a cheatin’ way to catch crabs in a bucket down on the creek. Dennis sits and listens while I join Capers-Willis at the stove, watching her stir a big pat of butter into creamy grits and then spoon smothered garlic crab on top. Ella approves, giggling at my clumsy attempts to extract the sweet crabmeat as she chomps right through a claw with her 86-year-old teeth.

BJ-Dennis-Gina-Capers-Willis.jpg

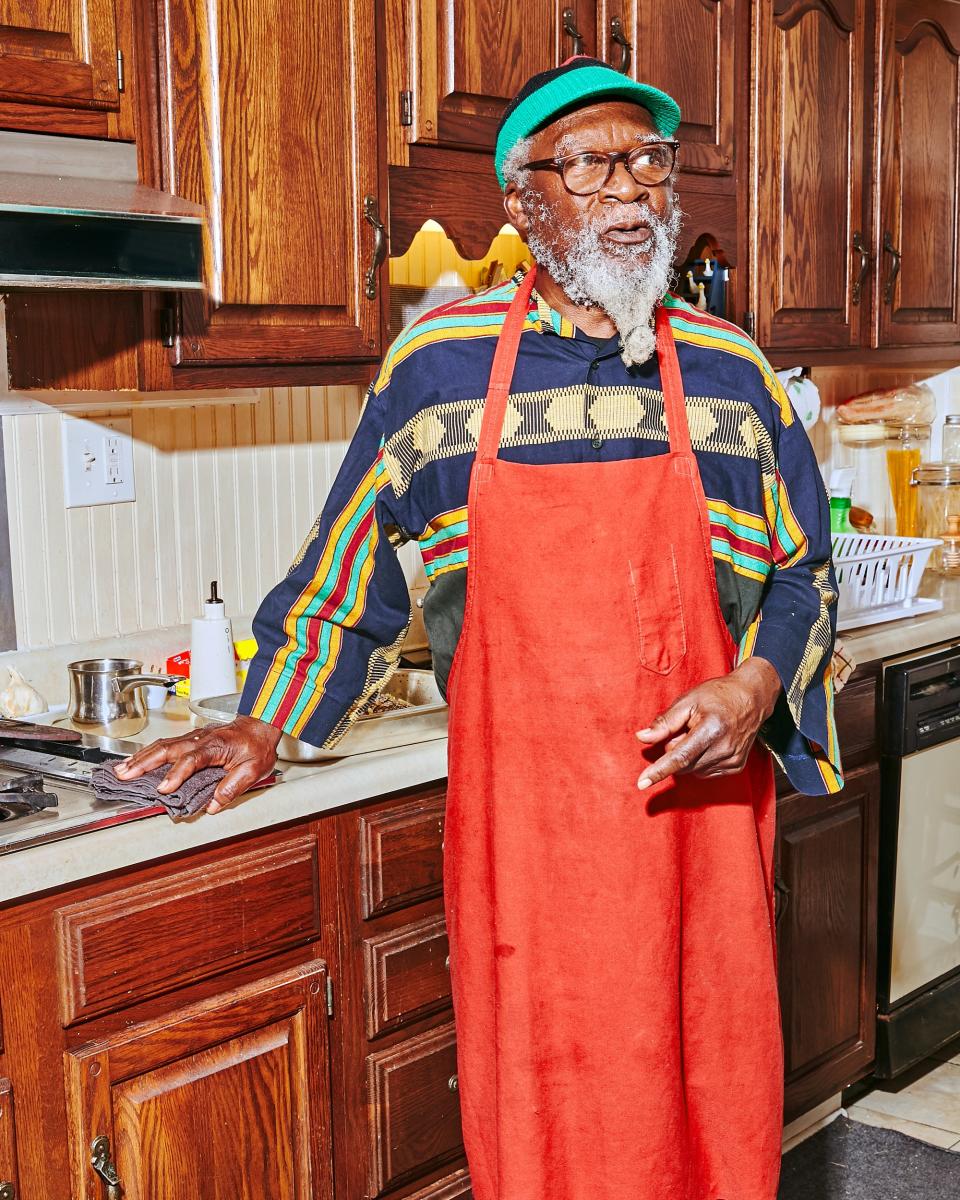

Our next stop is the chef Roosevelt Brownlee’s Savannah bachelor pad. When we arrive for dinner, he’s wearing a knit rastacap and a red apron over an African-print shirt, white beard tied in a knot below his chin. Back in the ’60s and ’70s, Brownlee cooked for American jazz musicians touring Europe—Nina Simone, Dizzy Gillespie, Sun Ra’s entire Arkestra (“Muddy Waters used to take his dentures out to eat my chicken!”)—but came home to Savannah and got overlooked for basic kitchen jobs.

“I guess they called me the rebellious one because everywhere I went I’d wear something representing Africa,” he says, sliding four of his famous Daufuskie deviled crabs into the oven, thorny shells filled with fluffy pillows of spiced crabmeat. Watching Dennis’s rise is the kind of triumph that feels personal. “I see him doing things I used to do. Man, they knocked me down.”

We sit down at the table, joined by Amir Jamal Touré, a professor at Savannah State University. “That’s why I work for myself,” Dennis replies, fixing himself a plate of Brownlee’s sheepshead fish and homegrown collards. “I don’t get into politics. I just talk about culture, my heritage, and my roots. I don’t know why people still get bothered.”

“Because they don’t know American history; they know American mythology,” says Touré. “That Gone With the Wind mythology.”

The men are solemn but hopeful, confident in their community’s ability to thrive despite it all. Outside, wild geese squawk at the setting sun. We bring our plates to the sink and ready ourselves to leave. Near the door, Dennis pauses, turning back to Brownlee and Touré. “I ain’t the first voice,” he says, “and I’m not gonna be the last voice.”

Brownlee nods, eyes serious behind his tortoiseshell glasses. “I’m just so glad there’s a voice.”

On our last day of the trip, we visit Brunswick, Georgia, where schoolteacher turned tour guide Helen Ladson is helping plan the area’s first Taste of Gullah festival at the historically black Harrington School Cultural Center on St. Simons. A celebration of Gullah music, crafts, and of course, food, this festival does locally what Dennis is trying to do on a national level: create visibility for the culture while simultaneously educating people about its history. At caterer Isaiah Brown’s house, we gather in the yard for barbecue and Frogmore stew: live crabs tossed into a boiling mixture of sausage, corn, crawfish, clams, and Cajun seasoning. “We ain’t family ’til we eat together,” says Ladson, handing me a plate.

Driving the three hours back to Charleston, I ask Dennis a question that’s been on my mind for miles: Does preserving this culture ever feel like a burden? He’s quiet for half a beat, then resolute. “No,” he says. “It’s never a burden because my ancestors walk with me every day. It’s a weight on my shoulders that I like.”

Later I ask Twitty the same question, and he points out the many ways modern griotdom can be hard: people who push back, who don’t understand, who try to trivialize what you do, who act like it’s just a hobby or a good deed when really it’s a job, the kind that requires financial and social support. “But one person’s burden is BJ’s joy,” he says. “BJ likes being a warrior for this culture. He revels in the challenge. And that is why I know he’s going to succeed.”

Now Dennis is working on going from full-time caterer to opening his own space. It will be in Charleston, but it won’t be just a restaurant. It will be a studio for kitchen demos, a venue, a casual café—a place where he can record livestreams and host dinners. In many ways the space will function as this road trip has: a platform for sharing Gullah culture in all its forms. That’s the way it goes with Dennis. He tells the stories of his people, and they, in turn, tell his.

A few miles outside Charleston, we stop at a gas station in the small town of Hollywood, South Carolina. Dennis runs inside to grab a soda. “Hey, come check this out,” he says when he returns, Styrofoam cup in hand, gesturing to a spot behind the mini-mart. A plume of steam rises from a silver vat as a man in overalls scoops boiled peanuts into a plastic bag. Behind him, fat peaches and plums sit in blue buckets on a folding table. Dennis has never met this man before, but we find out his name is Cornell Cox, and he’s been in this business for 52 years. I buy a sack of plums and Dennis takes out his phone, films an impromptu interview, and posts it to Instagram, entreating his followers to come down to Hollywood to get some of the goodness.

“You gon’ be back out here tomorrow?” he asks Cox, just before the video cuts out.

The man nods, turning back to his steaming pot. “I hope so.”

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit