The People Who Created Our Dictionary Have Been Largely Forgotten—Until Now

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

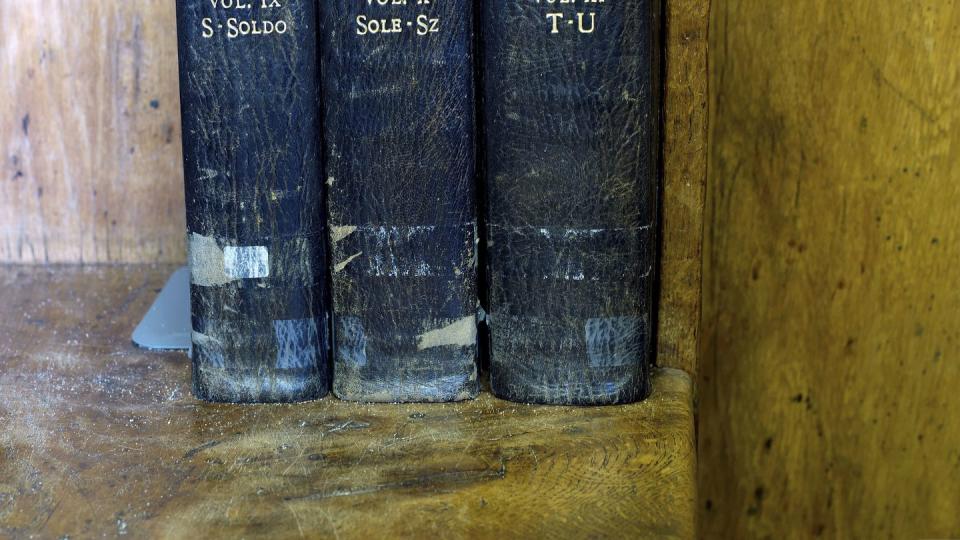

It was in a hidden corner of the Oxford University Press basement, where the Dictionary’s archive is stored, that I opened a dusty box and came across a small black book tied with cream ribbon. That basement archive is, strangely perhaps, one of my favourite places in the world: silent, cold, musty-smelling; rows of movable steel shelves on rollers; brown acid-free boxes bulging with letters; millions of slips of paper tied in bundles with twine; and Dictionary proofs covered in small, precise handwriting. It is a place full of friendly, word-nerd, ghosts. Perhaps those ghosts were guiding me because the discovery I made that day would lead me on an extraordinary journey and eventually to the book you are now holding.

I was there out of nostalgia more than anything. I used to work upstairs as an editor on the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) and I was filling in time while waiting for my visa to come through for a new job in America. It was Friday, and I had spent the whole week revisiting my favourite spots before leaving the city that had been my home for fourteen years.

Monday had been a walk around the deer park within the walls of Magdalen College. C. S. Lewis had said that the circular path was the perfect length for any problem. It was true. The fritillaria weren’t in flower, but the trees were yellow and the leaves on the ground were damp and smelled of the earth. Next, noisy Longwall Street and past the dirty windows of where I used to live at number 13. Through a heavy gate and an arch in the old city wall and into the vast gardens of New College with its immaculate lawn and long border still in colour. The bells rang as I paused at the spot under the oak where the college cat, Montgomery, had been buried by the chaplain. Along the gravel path by the purple echinops, crimson dahlias, and red echinacea with their pom-pom centres. Through the grand gates of the old quad, and into the silence of the cloisters where they had filmed Harry Potter. I pushed open the door of the chapel and was immediately hit by the comforting smell of beeswax and the sound of the choirboys rehearsing. I stayed in the antechapel and sat in front of Epstein’s Lazarus rising out of the tomb and spinning free of his bandages. Tuesday was the Upper Reading Room of the Bodleian Library. Wednesday was the secret bench against the President’s wall at Trinity College where I used to worry about my thesis. Thursday was Wolvercote Cemetery and the resting place of my hero James Murray, the longest-serving Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary from 1879 up to his death in 1915.

The Dictionary had started out with three men, Richard Chenevix Trench (1807–86), the Dean of Westminster Abbey, along with Herbert Coleridge (1830–61) and Frederick Fur- nivall (1825–1910), both lawyers turned literary scholars, who suggested the creation of a new dictionary. This would be the first dictionary that described language. Until then, the major English dictionaries such as Dr Samuel Johnson’s in the eighteenth century were prescriptive texts – telling their readers what words should mean and how they should be spelled, pronounced, and used. In 1857, these men proposed to the London Philological Society – one of the scholarly societies that were such a hallmark of their day – the creation of ‘an entirely new Dictionary; no patch upon old garments, but a new garment throughout’. Coleridge became the first Editor of the New English Dictionary (as the OED was first called), but he died two years into the job. Frederick Furnivall took over for twenty years, until he was replaced in 1879 by a schoolmaster in London called James Augustus Henry Murray (1837–1915).

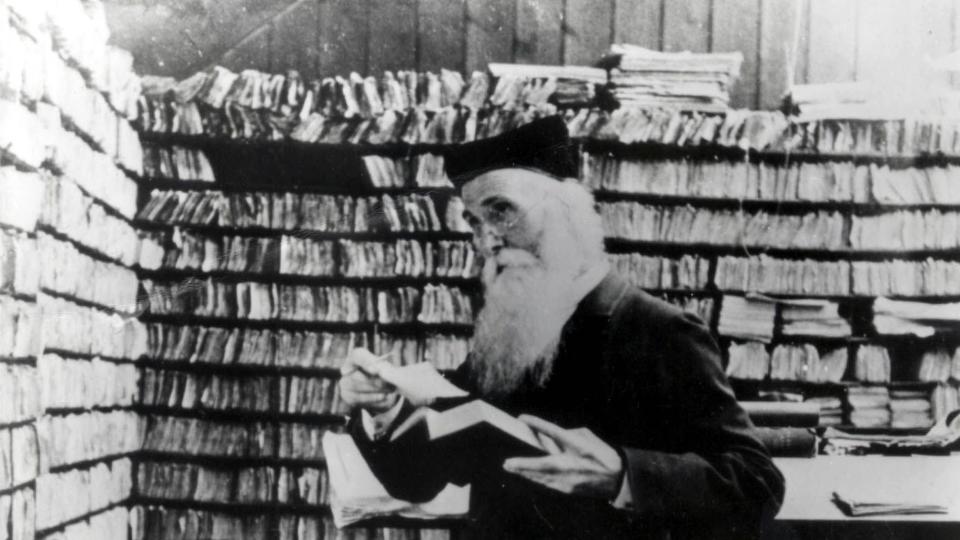

Before moving to Oxford, Murray tried to combine teaching at Mill Hill School with work on the Dictionary. The Dictionary won out. It was at Mill Hill that Murray had started to compile the Dictionary inside his house, but the vast quantities of books and slips threatened to crowd out his growing family (in time, he and his wife Ada would have eleven children). Ada eventually put her foot down, insisting that he build an iron shed in the garden and use that as his office; it was nicknamed the Scriptorium. When Murray moved to Oxford in 1884 to work solely on the Dictionary, his family and the Scriptorium went with him. It was partially dug into the ground, so Murray and his small team of editors laboured on the Dictionary for the next thirty years in dank and cold conditions, often wrapping their legs in newspaper to stay warm. Over the years, he was helped by paid editorial assistants and joined by three key editors who subsequently became Chief Editors in their own right: Henry Bradley, William Craigie, and Charles Onions.

The new Dictionary would trace the meaning of words across time and describe how people were actually using them. The founders, however, were smart enough to recognize that the mammoth task of finding words in their natural habitat and describing them in such a rigorous way could never be done alone by a small group of men in London or Oxford. The OED was the Wikipedia of the nineteenth century – a huge crowdsourcing project in which, over seventy years between 1858 and 1928, members of the public were invited to read the books that they had to hand, and to mail to the Editor of the Dictionary examples of how particular words were used in those books. The volunteer ‘Readers’ were instructed to write out the words and sentences on small 4 x 6-inch pieces of paper, known as ‘slips’. In addition to being Readers, volunteers could help as Subeditors who received bundles of slips for pre-sorting (chronologically and into senses of meaning); and as Specialists who provided advice on the etymologies, meaning, and usage of certain words. Most people worked for free but a few were paid, and the editorial assistants formed two groups – one under the leadership of Murray in the Scriptorium and the other managed by Henry Bradley at the Old Ashmolean building in the centre of Oxford.

In the first twenty years, this system of crowdsourcing enlisted the help of several hundred helpers. It expanded considerably under James Murray, who sent out a global appeal for people to read their local texts and send in their local words. It was important for Murray that everyone adhere strictly to scientific principles of historical lexicography and find the very first use of a word. Readers received a list of twelve instructions on how to select a word, which included, ‘Give the date of your book (if you can), author, title (short). Give an exact reference, such as seems to you to be the best to enable anyone to verify your quotations. Make a quotation for every word that strikes you as rare, obsolete, old-fashioned, new, peculiar, or used in a peculiar way.’ He distributed the appeal to newspapers and journals, schools, universities, and hundreds of clubs and societies throughout Britain, America, and the rest of the world. The response was massive. In order to cope with the volume of post arriving in Oxford, the Royal Mail installed a red pillar box outside Dr Murray’s house at 78 Banbury Road to receive post (it is still there today). This is now one of the most gentrified areas of Oxford, full of large three-storey, redbrick, Victorian houses, but the houses were brand new when Murray lived there and considered quite far out of town. He devised a system of storage for all the slips in shelves of pigeonholes that lined the walls of the Scriptorium.

We know some of the contributors’ names from brief mentions in the prefaces to the Dictionary that accompanied each portion (called a ‘fascicle’) as it was gradually published between 1884 and 1928. Other historical documents, such as Murray’s presidential addresses to the London Philological Society, also mention groups of contributors: some are famous, some ordinary, and some unpredictable – perhaps most notoriously the murderer and prisoner William Chester Minor, so brilliantly depicted by Simon Winchester in The Surgeon of Crowthorne (1998). Through these sources, historians have thought that there were hundreds of contributors, but have not known who they all were.

Today, crowdsourcing happens at extraordinary speed, scale, and scope thanks to the internet. In the mid-nineteenth century, the launch of ‘uniform penny post’ and the birth of steam power (driving printing presses, and leading to railway transport and faster ocean crossings) enabled this system of reading for the Dictionary to be so successful. The growth of the British Empire, the proliferation of clubs and societies, and the professionalization of scholarship throughout the century all conspired to create the conditions for a global, shared, intellectual project that continues to this day.

The OED is now on its third edition, and still makes appeals and invites contributions from the public (via its website), but is chiefly revised by a team of specialized lexicographers. As one of those lexicographers, my job was to edit the words that had originally come from languages out- side Europe – words from Arabic (sugar, sofa, magazine ) or Hindi (shampoo, chutney, bungalow ) or Nahuatl (chocolate, avocado, chilli) – in the third edition. Apart from the use of computers, the editing process I followed was exactly the same as that masterminded by Murray: each lexicographer was given a box of slips corresponding to our respective portion of the alphabet and, aided by large digital datasets, we worked through slip by slip, word by word, striving to piece together fragments of an incomplete historical record, until we had crafted an entry and presented a logical chain of semantic development in much the same way that Murray and his editors had. We also worked in a silent zone, just as it was in the nineteenth century. It has relaxed a bit now and editors work in small groups, but when I first started there if you wanted to speak to a colleague you were encouraged to whisper or to go into a meeting room to do so.

It was only natural that on my final day in Oxford I should want to bid farewell to the Dictionary Archives, where I had spent so many happy hours in the past. On that cool autumn Friday in 2014, when I casually popped by to pass some time, I could not have imagined what I was about to discover.

I collected my visitor’s badge from the reception and made my way along multiple corridors, down some stairs, along a tunnel. I had walked this way many times because I had also written my doctorate on the OED using historical materials stored down there. As a previous employee, I have always been granted exceptional access to the stacks. One last swipe and a loud click, and I was inside the inner sanctum of the archives. Bev and Martin greeted me; I passed through another door into the OED section of boxes and paraphernalia. It was the material relating to the first edition of the OED which drew me. It was a treasure trove. You could pick any box and it held something of interest.

I don’t even remember what was written on the one that I pulled off the shelf, but I noticed that it was lighter than the others. I placed it on the floor and lifted the lid. There, right on top, was a black book I had never seen before, bound with cream ribbon.

I carefully picked it up and removed the ribbon that held the stiff black covers together, and looked more closely. It was the size of an average exercise book; the spine had disintegrated to reveal fine cotton binding; the pages were discoloured at the edges, slightly foxed. When I opened it, the first thing that struck me was the immaculate cursive handwriting. I recognized it as the familiar hand of James Murray. He had written the names and addresses of not just hundreds but thousands of people who had volunteered to contribute to the Dictionary.

The Dictionary People: The Unsung Heroes Who Created the Oxford English Dictionary

amazon.com

$27.00

Finding Dr Murray’s address book was one of those moments when everything goes into slow motion. I immediately appreciated the significance of the find. I realized I held a key to understanding how the greatest English dictionary in the world was made: not only who the volunteers were, where they lived, what they read, but so many other personal details that Murray often included on their deaths, marriages, and friendships.

I was stunned by the transparent numbers of people who had contributed. Murray had not only listed the names and addresses of his contributors but had meticulously recorded every book title they had read, with the number of slips they sent in, and the dates received. Every page was filled with black ink: names, addresses, and titles of books with numbers beside them, small symbols and notes, ticks and checks, stars and scribbles.

I wondered whether I was the first person to open the address book since Murray had last used it. Had it remained closed for almost a century? Not quite: there was an archival classification number written in pencil at the top of one of the pages, and I knew that the dictionary archive had been re-organized and categorized by the Dictionary’s wonderful archivist, Bev. However, I was familiar with the books and articles written about the OED over recent decades, and I knew that it was likely that no one else had seen Murray’s address book or, if they had, they had not deemed it valuable. I was the first person to take this opportunity to track down who the contributors really were, and to build as comprehensive a picture as possible. I had found the Dictionary People.

The box in the archives held two further address books belonging to Murray, and the following summer, in a box in the Bodleian Library, I found another three address books belonging to the Editor who had preceded him, Frederick Furnivall. As I worked my way through them, it became clear that there were thousands of contributors. Some three thousand, to be exact.

The address books provided me with the kind of research project that scholars can only dream of. My excitement was followed by long, hard detective work. My visa came through and with the help of a team of tech-savvy student research assistants at Stanford (where I was by then teaching) I used the information from six address books (Murray’s and Furnivall’s) to create two large datasets of the thousands of Dictionary People and the tens of thousands of books that they read. In tracking contributors across the world, I visited libraries, archives, and personal collections in Oxford, Cambridge, London, New York, California, Scotland, and Australia. I also gathered portraits and digital photographs of the contributors, scanned hundreds of letters and slips showing the handwriting of the contributors, as well as great lists of the words and quotations they collected.

Murray’s address books were clearly the work of an obsessive. Piecing together the stories of the Dictionary People from his brief and often cryptic notes required a similar focus. Some pages held original letters from the addressees, and almost every page contained signs that needed decoding. What did Murray mean by D4, D6, a tilde accent, or a U with a cross through it? It took me a while to work those out, while others I immediately grasped – ‘11/2/85’ clearly meant 11 February 1885. Some people in the address books had cryptic marks and ideographs above their names. Others had not-so-subtle descriptors: ‘dead’, ‘died’, ‘gone away’, ‘gave up’, ‘nothing done’, ‘threw up’, ‘no good’. I sat with the books and studied their pages, and other patterns emerged. Some names were underlined in bright red pencil, and gradually I realized this meant they were Americans, while others were crossed out in blue pencil with the letters ‘I-M-P-O-S-T-O-R’ written over them.

For the past eight years I have pored over these address books, researching the people listed inside them – where they lived, what they did with their lives, who they loved, the books they read, and the words they contributed to the Dictionary. Some people have remained mysteries, despite my trawling through censuses, marriage registers, birth certificates, and official records, but many more have come to life with such force it is as though they have been calling out for attention for years.

The Dictionary was a project that appealed to autodidacts and amateurs rather than professionals – and many of them were women, far more than we previously thought. It attracted people from all around the world as well as Britain: from Australia, Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand, to America, Europe, the Congo, and Japan. Remarkably, they were not generally the educated or upper classes that you might expect.

Over the years that I have been researching them, I have fallen in love with the Dictionary People. Most of them never met each other or the editors to whom they sent their contributions, and most were never paid for their work. But what united them was their startling enthusiasm for the emerging Dictionary, their ardent desire to document their language, and, especially for the hundreds of autodidacts, the chance to be associated with a prestigious project attached to a famous university which symbolized the world of learn- ing from which they were otherwise excluded. The Dictionary People could also be cranky, difficult, and eccentric – as James Murray often found out – but that, paradoxically, also makes them lovable, or at least fascinating.

Tracking the lives of these three thousand people has been a long task and, yes, a labour of love. I have wanted to tell the story of the OED from the ‘bottom up’ through the eyes of the volunteers rather than from the perspective of the editors or the scholars. Murray’s incredible record-keeping in his address books made much of this possible, though some of those three thousand were easier to track through the many archives I consulted than others: the biases within record-keeping meant that there were sometimes frustrating gaps in the evidence and a skew towards certain classes, genders, and ethnicities. And yet the stories of so many were findable – and I often found them on the margins. Even James Murray was unusual in not being part of the Oxford Establishment – he was Nonconformist and Scottish, and had left school at fourteen. He was an expert in the English language but he was also somewhat on the fringes. The OED was a project that attracted those on the edges of academia, those who aspired to be a part of an intellectual world from which they were excluded. While I always wanted to find out more about Miss Janet Coutts Pittrie of Chester who is marked in the address book as ‘Friend of Miss Jackson’; Mr John Donald Campbell, who was possibly a factory inspector in Glasgow; and Miss Mary A. Pearson, who was possibly a cook and servant in Eaton Square, London, the details of their lives eluded me. But there were so many more whose life stories popped out in technicolour as I was doing my research. I was thrilled to discover not one but three murderers, a pornography collector, Karl Marx’s daughter, a President of Yale, the inventor of the tennis-net adjuster, a pair of lesbian writers who wrote under a male pen name, and a cocaine addict found dead in a railway station lavatory. In the process of searching for these people, I have come across many hundreds of fascinating and often unexpected stories – dramatic and quotidian. I became obsessed with shining a light on these unsung heroes who helped compile one of the most extraordinary and uplifting examples of collaborative endeavour in literary history.

The time that the Dictionary was being written was an age of discoveries and science, an explosion of modern knowledge, and we see in so many of the rain collectors, explorers, inventors, and suffragists how much our current world was shaped by this relatively short period. There is a paradox about the very project of the Dictionary, the words collected for it and included in it. The Dictionary enterprise can easily be seen as a mastery of the world for the sake of the English language and the intellectual pas- sions of white people. Murray’s commitment to including all the words that had come into the English language may be seen as colonizing – or it may be seen as inclusive. Murray went out of his way to include all words, often being criticized for it by reviewers of the Dictionary and his su- periors at Oxford University Press. This means that the pages of the Dictionary incorporated words from the languages of Black and indigenous populations, and of people of colour. The Dictionary People who sent in those words were, for the most part, white, because of their privileged access to literacy in the period. The published sources of those words drew originally on the language of members of Black and indigenous communities whose names never made it into the pages of Murray’s address book, and it is important to acknowledge those often unseen and unrecorded interlocutors.

A myth of Murray has persisted as the Editor who devotedly and single-handedly created the world’s largest English dictionary with its half-million entries – only to die during the compiling of the letter T in 1915, not knowing whether his life’s work would ever be finished. While Murray was clearly a master-manager of the whole Dictionary project and had a small number of paid staff in the Scriptorium, this oft-told story ignores all the many people who corresponded with him and sent him words and quotations which made the Dictionary happen. The photograph in the Scriptorium might show only five men, but a careful observer will see the volunteer contributors clearly present, there in the thou- sands of word slips they sent, poking out of the pigeonholes. It is their lives that I unearthed and relate in this book.

The story here is one of amateurs collaborating alongside the academic elite during a period when scholarship was being increasingly professionalized; of women contributing to an intellectual enterprise at a time when they were denied access to universities; of hundreds of Americans contributing to a Dictionary that everyone thinks of as quintessentially ‘British’; of an above-average number of ‘lunatics’ contributing detailed and rigorous work from mental hospitals; and of families reading together by gaslight and sending in quotations. This extraordinary crowdsourced project was powered by faithful and loyal volunteers who took up the invitation to read their favourite books and describe their local words not just so that the bounds of the English language could be recorded for future generations but so they could be part of a project that was much bigger than them.

They are the Dictionary People, largely forgotten and unacknowledged—until now.

From THE DICTIONARY PEOPLE: The Unsung Heroes Who Created the Oxford English Dictionary by Sarah Ogilvie. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Sarah Ogilvie.

You Might Also Like