Peeling back the layers of the extraordinary vegetable found around the world

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

At this very moment, cooks around the world are standing in their kitchens, slicing and dicing onions and having a collective cry. Those tears are the price they pay for that soul-warming stew, heady stir-fry, savory custard pie, earthy bread or tongue-tingling salsa that will soon grace their tables.

All thanks to the humble onion.

Onions are the second-most-produced vegetable in the world, surpassed only by tomatoes, which, botanically speaking, are a fruit. Julia Child famously said she found it “hard to imagine a civilization without onions.” Her friend and fellow television cooking pioneer James Beard, who often professed his enthusiasm for onion sandwiches, deemed the ubiquitous vegetable “a thing of beauty in itself, and certainly a gastronomic joy that should never be taken for granted.”

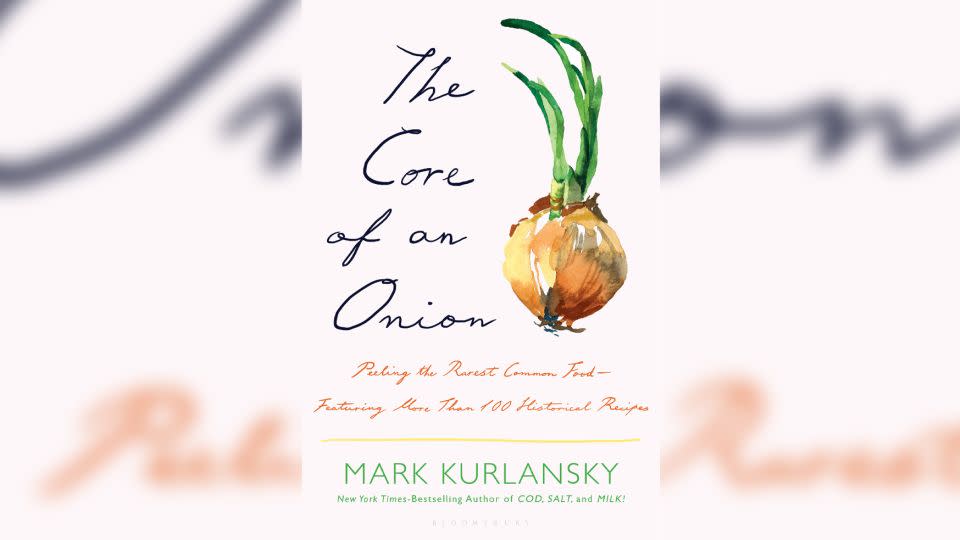

In his new book, “The Core of an Onion,” Mark Kurlansky presents a lively collection of fun facts and lore to help us better appreciate the significance of this plebeian pantry staple in our kitchens and throughout world history.

Kurlansky also offers insight into how onion cookery has evolved through the ages with recipes gleaned from old texts, including the 18th century onion soup favored by King George II and the lemon pie made with pureed boiled onions that won first place in the cook-off at the 1987 Vidalia Onion Festival.

Kurlansky is well-known for choosing a seemingly mundane singular subject — often, but not always, edible — to unravel a global story. His 1997 book, “Cod: A Biography of a Fish That Changed the World,” became an international bestseller that’s been translated in 15 languages. “Milk!” “Paper: Paging Through History” and “Salt” are among his other titles.

I called Kurlansky at his home in New York City to learn more about peeling back those layers.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

CNN: What prompted you to embark on this onion odyssey?

Mark Kurlansky: I thought that onions were being underrated. They’re always around, and everybody uses them. You know, there’s a difference between something being common and being ordinary. Onions are common, but they are actually an extraordinary thing. They’re very unusual — both biologically and gastronomically. And because of these unusual qualities, they’re used just about everywhere in the world. One of their unusual qualities is that they can grow anywhere — in tropical, arid and even arctic climates.

CNN: Do people really eat onions whole?

Kurlansky: It’s a thing in certain places in the world to eat onions whole — and not even sweet onions. Especially in parts of central Europe. I remember traveling around what was then Yugoslavia by train, and people were just sitting around munching on onions.

CNN: That is rather hard to visualize.

Kurlansky: Certain people have done it, and they’re always looked down upon. It’s often considered a low-class thing. It’s even in “Don Quixote,” when (the mad knight in the 17th century novel) tells Sancho Panza (the illiterate farm laborer who becomes his squire) that he looks very low-class eating onions.

The English in the Middle Ages and even later would talk about what backwards people the Scots were. I went to Scotland and you can’t believe these people; they just sit around munching on onions. And when the Arabs controlled Sicily, they claimed that the people of Palermo were very dumb and backwards because they ate raw onions. Onion on bread was a poor people food in London and in a lot of places, actually. Portugal, too.

CNN: You also developed a taste for this combination early in life?

Kurlansky: Onion rye — yeah! Supposedly I took a loaf of onion rye and hid under the bed and ate it. I remember loving the onion rye. I don’t remember the “under the bed” part. It might be true.

CNN: I don’t think of onions as being something children like.

Kurlansky: I did! I may have been an odd child. When I was a kid, one of my favorite things was vichyssoise soup. I love vichyssoise! This cold creamy (potato and leek) soup with little green dashes of chives on top.

CNN: Did you come from a cooking family?

Kurlansky: My mother was always in the kitchen cooking something. We were a family of six, and she did cook every night. She did an enormous amount of baking. We had pies and cakes sitting around in the house all the time. And her mother cooked a lot also. They were from Lithuania, and my grandmother moved to the Lower East Side of New York when she was a child, so she basically grew up on the Lower East Side. She always cooked Jewish food. And made a lot of strudel.

CNN: How and when did you get into Basque culture?

Kurlansky: In the 1970s when Franco was still in power in Spain, and Spain was like a 1930s fascist state giving fascist salutes, the whole thing. And nobody was writing about it anymore. So, I went to all these American newspapers and …. said I want to go to Spain and write about the resistance to the last fascist government. And everybody said great! Nobody was doing anything to resist except the Basques. I went there, and it’s one of the most beautiful places on earth. It’s a fascinating culture, and so I just became completely taken with it. Really great salt cod dishes — better than anywhere else.

CNN: Onions are part of just about every cuisine. Are there differences you’ve observed about onions from the different places you’ve lived in?

Kurlansky: There are differences, and there are some things that are true everywhere. Everybody who makes a stew starts with onions. There’s an Andalusian thing that making a stew without onions is “like trying to sing a song without a tambourine.” And then there are curious local things everywhere. The elaborate Hungarian-stuffed onions. And the Basques use onions instead of rice as filler to make blood sausages. Blood and onions is a Basque thing, but it’s also a Catalan thing. And a Hungarian thing, and it’s also in some French cuisine. It’s something that keeps turning up.

CNN: Your recipes are fascinating to read, but not exactly designed for the modern kitchen. Did you make any of them?

Kurlansky: All I’m saying is this is an interesting recipe. I’m not guaranteeing that this will be a great dish. There’s a Peruvian one called encebollada, which is one of my favorite onion dishes (and literally means “onioned).” And if you look at the recipe, you’ll notice that it’s almost the exact recipe for ceviche — but with onions instead of fish. It was like poor people’s ceviche.

CNN: I could see how the texture of the marinated onions could come out fish-like.

Kurlansky: I like to make a bunch of it and keep it in the refrigerator and just put a spoonful on different dishes. It brightens the plate, and it’s this great condiment. Onions and lime are two of the strongest flavors, so you put them together and have them duke it out. But it’s nice the way the red pigment from the red onions gets released by the acid from the limes and turns the whole thing this bright fuchsia color. It brightens up anything, both visually and taste wise.

With encebollada, there’s this whole controversy whether to sprinkle cilantro over the top or not. And of course, cilantro just seals it as ceviche, right? But a little bright green on top of the bright fuchsia is really just perfect.

CNN: Do you have a favorite onion?

Kurlansky: For raw onions I like red. For cooking … I get whatever kind of sweet onions are available. For certain kind of things, you want stronger onions. And for certain cuisines. Onions in India are quite strong because it’s a hot climate. So, if you want to make Indian food that tastes anything like what it tastes in India, you have to come up with strong onions.

CNN: Let’s talk about crying while cutting onions. A number of methods to prevent it are quite creative — like lighting a match or biting on the handle of a wooden spoon.

Kurlansky: Most of them don’t work. The simplest solution, which is almost never suggested, is just to wear glasses. It’s not 100%, but it does help. And you can get onion goggles.

CNN: You do need to cover your nose up, too.

Kurlansky: You do! The nose leads to the eyes. Which is why wearing glasses doesn’t totally work. Another thing that has some science to it is to chop onions under running water. It doesn’t entirely work, but the reason it somewhat helps is because what happens when you chop into an onion is the onion fights back by releasing this sulfuric gas, which is drawn to water. When it hits the water in your eyes, it turns into sulfuric acid, and that’s why it stings. But if you have another water source, it will divert some of that gas.

Susan Puckett is the former food editor of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and author of “Eat Drink Delta: A Hungry Traveler’s Journey Through the Soul of the South.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com