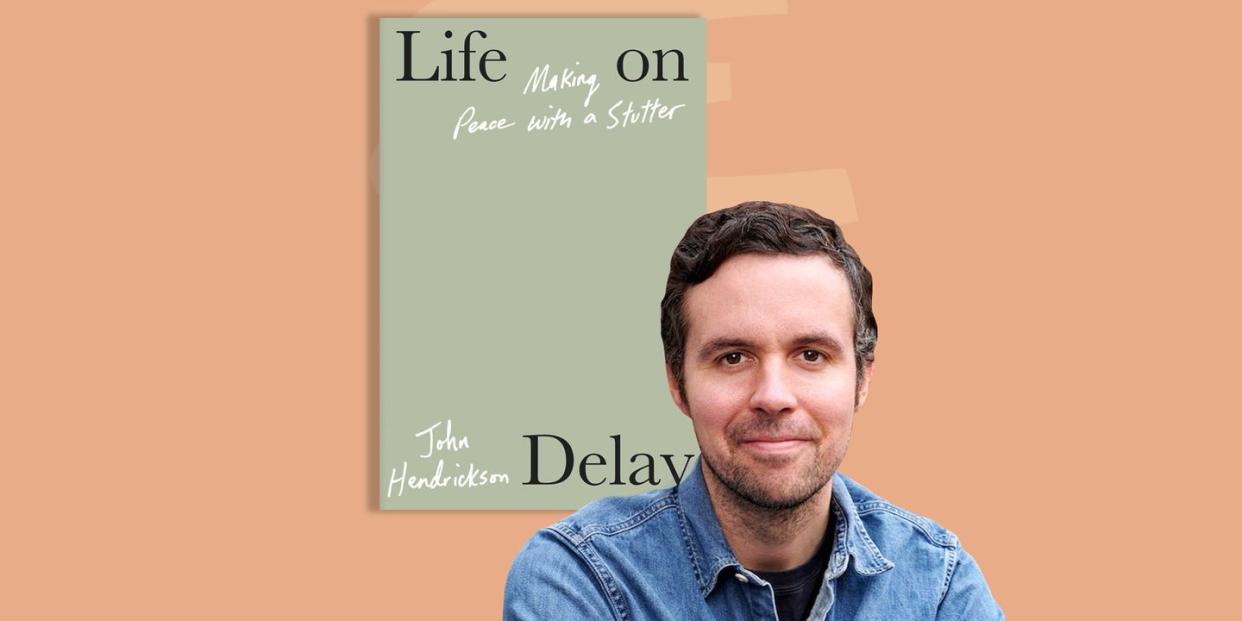

How John Hendrickson Writes What's Real

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

The first pages of John Hendrickson’s memoir, Life On Delay: Making Peace with a Stutter, set a scene: he’s in MSNBC’s green room, following publication of a story for The Atlantic that would ultimately change his life. “As I listened to the recording of our interview, I remembered how I used to respond when people asked me about my stutter. I’d shut down. I’d try to change the subject,” Hendrickson (a former Esquire editor) wrote then. The interviewee was then-presidential candidate Joe Biden, and in the hours following publication of the piece, “Joe Biden’s Stutter, and Mine,” personal stories poured into Hendrickson’s inbox.

Life on Delay is the opposite of “shut down, change the subject”—it’s personal, investigative, and brimming with curiosity and empathy. Grounded in Hendrickson’s personal story, the book interweaves research, telling us it’s only since the turn of the millennium that stuttering has been understood as a neurological disorder, with reporting, where Hendrickson interviews stutterers around the world, including many who sent him messages in 2019, and people he’s known throughout his life, including his kindergarten teacher. As a chronically ill person, Hendrickson’s examination of shame, time, and selfhood hit me in the gut; as a lover of memoirs, the book’s insight into relationships, with others and ourselves, nudged me toward reflection on what it means to understand all the parts of who we are.

Hendrickson and I are speaking via phone—he dreads phone calls; I tell him there’s a 50-50 chance I’ll disrupt our conversation thanks to my stomach issues—the week before Life on Delay publishes." “It's an indescribable feeling,” he says of holding finished copies. “It’s a moment I'll cherish for the rest of my life.” This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Esquire: Did you always know that this was going to be the book you’d write—and if not, when did it click for you that this story was a book?

John Hendrickson: Prior to the fall of 2019, when I first wrote about Joe Biden's lifelong journey with stuttering, I had never written anything about the topic of stuttering, or about my stutter, for public consumption. I never talked about it. So no, this is not a book I always thought I would write. But writing that article changed my life. It began to open up this part of me. After it was published, I received dozens, and then hundreds, and then over 1,000 messages and emails and letters from other people who stutter, sharing their own life stories—that made me think that there was something here.

I wanted to ask about this outpouring of messages. I’m thinking especially of Hunter, a 32-year-old attorney featured in the book; you describe his initial email as life-changing. What was the process for deciding which stories would be part of the final copy?

When I would receive these emails and letters and messages, I read and responded to every one, but it took me a long time. In the summer of 2020, when I signed the book contract and began working on the research and reporting and interviewing part of this book, I went back to some of those emails I had starred, and I reached out to these people again, even though in some cases, we had been regularly corresponding that whole time.

Life on Delay: Making Peace with a Stutter

amazon.com

$29.00

amazon.comIn the case of Hunter, what jumped out at me was the fact that we were the same age. He lived in Denver, and I lived in Denver for a couple years after college. He was a lawyer and I was immediately interested in that—I'm like, wow, what must it be like to be a lawyer who stutters? We just had this rapport. We had long interviews over many months remotely. Then I went and visited him in person, and got time with him and his family, in the summer of 2021. During the course of our time knowing each other, Hunter was diagnosed with colon cancer, and our conversations were about everything—they were about being people who stutter, they were about his cancer journey. Hunter died before it [this book] went to press. It was actually the anniversary of his death last week. I kept in touch with his widow, who is just an amazing person and is raising their young daughter. This whole last period of my book project, when I've had moments of peak anxiety, peak insecurity, peak self-doubt, and negative self- talk, I've prayed to Hunter and I've asked him for help. I've just sort of tried to commune with him mentally. I can feel him there. I can feel us in conversation still. I only knew him for a few years, but he made a profound impact on my life.

There’s a line in the book about Hunter wanting people to think of him as Hunter during his illness, which is also how he lived his life as a stutterer. Something I thought came through is that this isn’t a book that’s about “overcoming” a disability, or other faux-inspirational, problematic narratives, or about reducing stuttering. It feels like so much of it is about understanding all parts of who you are.

That was absolutely my goal. This is an adult book. It's aimed at adults, and there are adult themes, but in a lot of ways, I was writing this book for my teenage self, for my early college self. I was just trying to create the work that would have helped me back then, and being a moody, angsty teenager, the last thing I wanted to read was an inspirational, Hallmark movie thing. What I find resonates is just being real and trying to convey the totality of daily life, which is good, bad, happy, sad, and everything in between. It's never just one of those emotions; it’s frequently all of those emotions at the same time. Maybe one pulls ahead for a couple hours and then another emotion pulls ahead the next couple hours. I wanted to just write a book that felt real and true.

I loved the sections of the book about young adulthood, because I think about that time in my own life, and the shame I felt. There’s a line in the book that says: “Guilt is, ‘I made a mistake.’ Shame is, ‘I am a mistake,’” which I think totally captures that sensation. How did it feel to try to put that feeling down on the page?

That quote came from a friend who stutters, and the moment he said it, I wrote it down, put it in quotation marks, and I'm like, this is absolutely going in this book, because it felt like a perfect distillation of something I had been searching for my entire life. The subtitle of this book is “making peace with a stutter,” because that was really my north star. To me, there's a difference between curing something and making peace with something.

To me, making peace with shame is knowing it may be there in some capacity for the rest of your life, and just acknowledging its existence, being okay with it, not running from it, not hiding from it, and learning how to keep living a good life even if the kernel of that is always with you. I think those lessons came when I went to psychotherapy around the age of 30. That broke me out of this antiquated mindset of you're either happy or you're sad. You're either on track or you're fucked up. I’ve just been trying to let my mind fully understand that you can be a lot of things at the same time, and that's okay.

You write about depression and OCD, two things that impact my life, as well as substance abuse. I appreciated how you explored how many layers there can be to someone’s experience.

What I found in my conversations with other people who stutter, these issues kept coming up—all the issues you just named, but also difficulty in securing employment, dating difficulty, many, many myriad issues. These are all issues for a number of people; you don't have to be a person who stutters, you don't have to have a disability. But it was important to me to acknowledge those layers of being a disabled person. Because just to get back to the first thing we talked about, the only thing you typically see and hear is an inspirational story of overcoming impossible odds. You don't as often hear about the daily layers of life. I think that's just a more realistic portrait.

Relatedly, I wanted to ask about the ableism in our structures and systems, from work, to school, to even dating, all of which have scenes in your book. How did you think about all of this while writing and reporting?

When I wrote my Atlantic article in 2019, that was really the first time I'd ever dug deep into the topic of stuttering, research, interviews, and otherwise. In the course of that process, I learned that stuttering is a neurological disorder with a genetic component, and that it's considered a disability. I had never known any of that for my whole life. It was always just my problem, my thing, and part of that is due to the evolving nature and understanding of it. It's wildly misunderstood. In the past 20 years or so, we've learned so much more about it. When I was a kid, my generation, the millennial generation and the generations above us, we all received a pretty antiquated form of therapy that was all focused on perfect fluency, talking perfectly smooth. It was an unrealistic goal. Now kids are more likely to receive a therapy that's just trying to help them manage the existence of their stutter, build up their confidence to talk and maintain eye contact and work through a block or repetition or prolongation, as opposed to running from it and hiding from it. So I don't blame anyone. I don't blame any old therapist. But I'm so thankful that kids today are growing up in a world where we have a more nuanced understanding of this disorder.

This reminds me a little bit of what you wrote: that prior to the Biden story, you didn’t know there was a stuttering community.

It never dawned on me to Google “stuttering support group” or “conventions for people who stutter” or anything like that. Obviously, I knew there were other people out there in the world who stuttered, but because I never talked about it, and because I never sought out these communities, I just sort of ignorantly assumed they didn't exist. Meeting so many folks within these communities has been a life-changing experience. They’ve taught me many, many things and have become good friends. I'm just so grateful that I have now integrated this into my life.

Another thing that came through strongly in this book was the focus on relationships. There are elements of getting to know new parts of ourselves, or relearning parts of ourselves, in different relationships, communities, or familial contexts. What was the process of writing about those relationships like?

My brother and my parents have been so incredibly supportive and generous with this entire project. They are my rock. They are my biggest champions. They've shown me such profound love with this journey I have been on ever since writing that article. One manifestation of that was when I asked them, “Can I interview you for this book? Can we sit down and just talk about life, the good, the bad and everything in between? ” And all three of them said, “Yes, we'll do whatever you need.” It was just so completely selfless of them and I don't know if I'll ever be able to repay that. But they just love me that much. They also believe in this project and they believe it can help other people and other families. I'm in awe of them.

It changed every single relationship in my life for the better, and it fostered new relationships with total strangers that continue to this day. There are people who I met over an email, who I then went on to talk with for many hours across many months, who I then went on to get to know in person, who I am planning to see in person in a couple weeks when I'm on my book tour. To think all that just came out of thin air is just amazing. I'm so grateful for it.

Something else that came through for me was a sense of time–you state that your stutter can feel like a waste of time, you note that people saying “take your time” is loaded, and we’re moving with you through time in the book. How does time feel to you right now?

One chapter in the book is a profile of JJJJJerome Ellis, who's a multidisciplinary artist, poet, musician— there's no way that you could ever describe JJJJJerome as just one occupation. Many people came to know JJJJJerome through an episode of This American Life that focused on rules meant to be broken, in which JJJJJerome’s disfluency broke a time limit at this public reading event. It was very, very cool—it was almost like an act of protest. JJJJJerome says this to me in the book, but it's not about stuttering, it's about time—the way the world has set these time parameters of everything from how long it takes a person to say hello when they pick up the phone to how long it takes them to place an order at a restaurant. Being out of sync with those established time norms is really hard. That is absolutely something that I explore in the book.

My sense of time is completely messed up. That's partly because I began scribbling down those little notes in a moleskin in late February 2020, and two or three weeks after that, the world stopped. The whole time that I was crafting this book coincided with the core pandemic years in which everybody's sense of time messed up. But I am so grateful to be at this point of getting ready to publish this book just about three years after I scribbled down those ideas.

What surprised you the most during the reporting and research process?

When I reached out to people from my past, such as my kindergarten teacher, my second grade teacher, my sixth grade girlfriend—these are people whom I hadn't been in touch with in 20, 25, 30 years. I had no idea if they would remember me. I had no idea if they would remember my stutter or have anything to say about it at all. I really just went out on a limb with that question, and said hey, remember me? Remember this thing that we never talked about? Can we talk about it now? I was just so completely floored when they were like, absolutely. I would love to talk to you. They had these extremely vivid memories and anecdotes that I remembered, but in some cases, things I had momentarily forgotten. When they began to tell me a story, then it would come immediately flooding back, as if someone turned the lights on in a room. Those conversations were just such a cool, fun part of this book, and it's such a weird excuse to reconnect with someone who you lost touch with decades ago. I've kept in touch with them ever since.

Early in the book, you describe repetition, prolongation, and blocking, and note that it's helpful to think of stuttering as an umbrella term to describe a variety of hindrances in the course of saying a sentence. What was your process of breaking down how these elements sound in writing?

That was a difficult writing decision. I wanted to visually represent it, but I also was cognizant of not constantly bringing the reader out of the story. When you see words or sentences that look quote-unquote weird, it takes your mind out of the book. So I tried to find some happy medium of displaying my own disfluency visually, but not displaying every single moment of disfluency that ever occurred in these interviews and in the conversations. It was a careful choice with every page, every chapter of okay, should this be a visual stutter, or not? I tried to be authentic to the experience but I also wanted to keep things readable.

Is there anything we haven't talked about in this conversation that you think it's important for people to know about this book?

You don't have to be a person who stutters to get something out of this book, and you don't have to have a disability to get something out of this book. Those are the prisms through which I'm trying to write about life, and that may sound really cheesy and really broad, but that's the truth. This book is not preachy; it’s not a medical science book. And it's not even self- help. It's just about confronting the tension between things we can change and things we can't change, and in a way, it's about auditing those two categories. Sometimes we think we know what we can change and sometimes we're wrong. It's just about unpacking all of that.

You Might Also Like