Paulina Porizkova Takes an Unfiltered Look at Anxiety in Her New Book

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

I readied myself for the forty-five-minute subway ride from Manhattan out to Brooklyn. I was fifty-three, and I was about to pose for a nude photo shoot for Sports Illustrated. At home, to prepare for the expedition, I filled my spray bottle with water and packed my paper fanfor when I needed to wet my face and get air moving over it. I checked that my bottle of antianxiety medication was in my bag, just in case. Just knowing it’s there helps me, even though it takes an hour to kick in if I take it. I dressed in layers, ready to shed down to a cotton tank if needed, even in the middle of winter. All the layers have to be easy to remove, cardigans or zip-ups. Nothing over the head. I packed tissues, a doggy bag in case I (or anybody else on the subway) threw up, and a Ziploc bag full of ice.

I thought of all possible scenarios. The train stopping, the lights going out, the conductor announcing something ominous over the PA system. This being New York City, the PA system on the train is always totally unintelligible, and I would have no idea what the driver just said. It could be that we were stopped temporarily, or it could be that we were all going to die. We could be stuck in the car in the middle of summer— the doors won’t open and the air conditioner goes out and we’re trapped for hours, trying to claw open the windows as we slowly cook. In winter, the rails on the Manhattan Bridge could freeze over and the train could skid off the tracks and careen into the river. I’ve taken classes on what to do if a terrorist sets off a bomb or throws an explosive in the train (don’t try to run—get down on the ground), as well as classes on what to do if someone attacks you with a knife or gun. I’m prepared for anything.

Finally, I headed out the door and started walking to the nearest subway station.

This is my routine—my preparation—every time I leave the house to go on the subway.

Contrast this with the preparation I needed to take the nude photos once I got to the photographer’s studio: I took my clothes off.

I’m often told that I’m a brave person for modeling nude, for standing in front of a photographer with no clothes, for daring to show the world my apparently shocking over-fifty-year-old body. I realize that for some people that would take a lot of courage. But that is not what takes courage for me; that is not where I need to muster all my strength and be brave. For me, bravery is leaving the house.

I have suffered from an anxiety disorder for most of my life—ever since I was taken away from Babi, my grandmother who raised me, and the world I knew. I had my first panic attack at the age of ten, in the middle of the night at my father’s house. I was sleeping in a little rollaway cot at the foot of his bed, my four-year-old brother in a separate cot next to me. I woke up feeling sure that I was about to die. My heart was slamming so hard against my chest I thought I could see it pulsating through my rib cage. The air had suddenly become too thick for me to breathe. It was like trying to suck in oxygen through a straw. My whole body shook. My father and his new girlfriend were sleeping in their big bed. I barely knew them. I had lived in Sweden a year at this point, but I longed for my grandmother. She was back in Czechoslovakia, unable to leave while I was unable to return. My father and his girlfriend were two strangers to me; I wasn’t sure that they liked me or wanted me to be there. Waking them up to tell them I was dying was a scarier prospect than just carrying on with death.

I rolled out of the cot and crawled to the bathroom. The toilet was in its own little room with a bright yellow light overhead. It felt like there was a huge, jagged rock inside me that expanded with every breath, squishing aside my lungs and heart and other organs with every gasp. The cold tile floor hurt my knees. My heart kept punching my ribs so hard it was as though it were trying to escape. I sat on the floor, rested my head on the toilet seat, and waited to die.

Clearly, I survived my first panic attack. But they kept happening. My mom was studying to be a nurse, so I used her medical textbooks to diagnose myself with a heart arrhythmia.

But I didn’t dare mention this diagnosis to anyone, especially not my parents, who already seemed to find me undesirable. If they found out about my heart condition, they might abandon me again. It was like I was walking on a very narrow ledge, and any gust of wind would take me down—on one side was sudden cardiac arrest, on the other, abandonment.

I was diagnosed with anxiety in my early twenties. I was delighted to know that I didn’t have a heart arrhythmia and that I was not going to die. Well, at least not from a heart arrhythmia. But it turns out there are a million and one other ways to die. People with anxiety tend to fall into two categories: the ones who fear they are going crazy, and people who fear they will die. I’m the latter.

Anxiety is not easily defeated. Once I lost the fear that my heart was going to take me down, I began to obsessively think about all the other possibilities. Plane crashes. House fires. A burglary gone wrong. Scaffolding collapsing on me as I walked underneath it on the sidewalk. Tsunamis. A giant icicle spearing me through the top of my head. Being stuck in the middle of the ocean on a boat that had run out of gas in a storm. What I began to notice was that the situations I most feared were all ones where I wasn’t in control. Where I was at the mercy of nature, of chance, of other people’s bad decisions. It’s the same sense of helplessness that I feel every time I walk into a packed elevator, get stuck in a traffic jam, or see the doors of a crowded subway car slide shut.

I’ve been told that posing naked at an age when you should be invisible is brave. American women are taught that removing your clothing is like removing your protective suit of armor. Revealing your flaws is incomprehensible in a culture that thrives on imagined perfection.

My true vulnerability lives in the things no one can ever see. The symptoms of severe anxiety are internal.

I have had all kinds of therapy, but ultimately, I have accepted that I am a person with anxiety, just as I am a person with blue eyes, a person who likes to read. I’ve learned to cope with my anxiety attacks through breathing techniques. And carrying ice. And the spray bottle. And all the rest. I’ve created a safety system for myself. This coping system does not eliminate the panic attacks, but it does mitigate them. It arms me for the battle. It allows me to live in the world and do the things I want to do, even though I know it will hurt, even though I know it will be a struggle every single time.

Learning not to panic when I can’t breathe. Learning to stay when I want to run. Learning to look when I want to avert my eyes. This constant war with myself has, in fact, made me who I am: brave enough to leave the safety of a marriage, brave enough to rebuild myself and my life, and brave enough to talk about it.

No one is born with courage. It is built over the course of a lifetime. It’s not just the moments that have made your heart break, or race, or bleed that have made you brave. It’s your response to those moments. It’s your willingness to confront your pain and fear. I built my courage one subway ride at a time. You build your courage your own way, by confronting your pain and fear, whether or not anyone else can see or understand them.

Being courageous hurts. It’s a painful process. But if you can accept this—if you can overcome your reluctance to engage in something difficult and scary—you will come out braver than you were yesterday. You can be the hero of your own life.

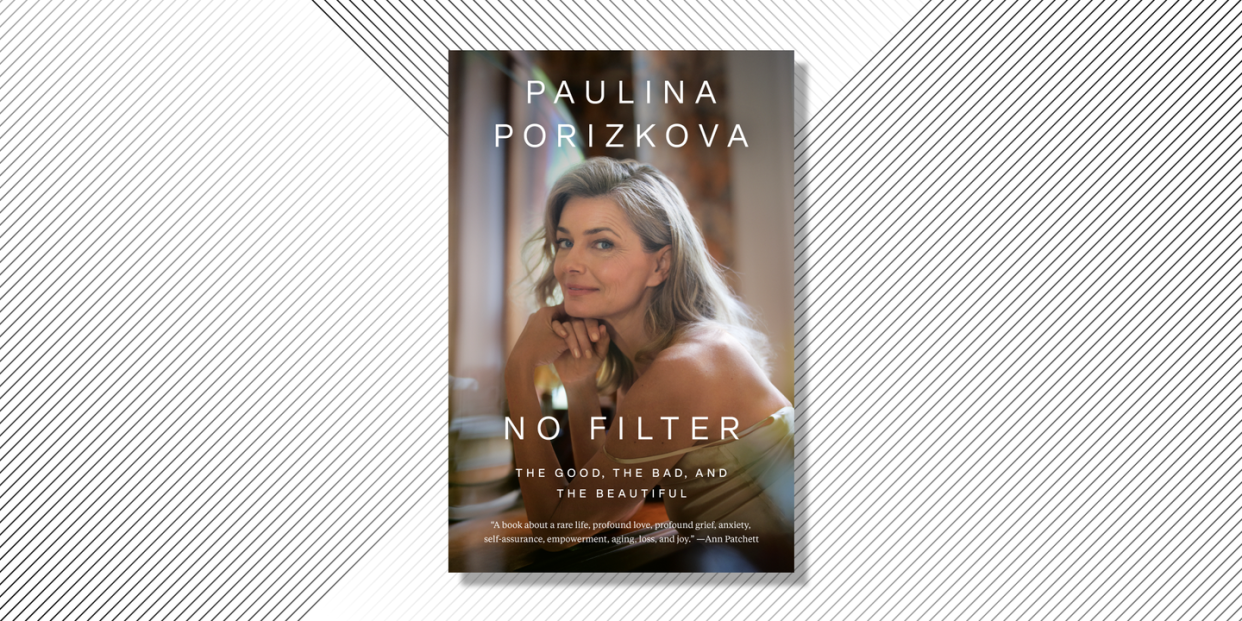

From NO FILTER by Paulina Porizkova, to be published on November 15, 2022 by The Open Field, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Paulina Porizkova.

You Might Also Like