Paul McCartney Photographs 1963-64: Eyes of the Storm review: Macca’s remarkable snaps capture the buzz of Beatlemania

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

For the National Portrait Gallery’s first major exhibition since reopening, it’s hard to imagine a more bang-on-target choice than this. Here we have 250 unseen photographs from Paul McCartney’s personal archive, chronicling the height of Beatlemania – and the vast majority taken by the ex-Beatle himself. Not only is it a guaranteed draw, at a time when public galleries need funds like never before, but it’s hard – the royals aside – to find a more unifying embodiment of British identity than The Beatles. They were forward-looking and turned the class system on its head (or so we’re endlessly told), but they were also in love with the British past – with music hall and Alice in Wonderland. Wherever you stand in the so-called culture wars, you’ll find something to hang on to in The Beatles.

Captured here is the great Beatlemania moment of 1963-64, with its multitudes of screaming teenagers, when the entire world seemed to stop what it was doing to watch the four Liverpool lads’ televised progress through the world’s airports and stadia. It’s a vital cultural episode that never loses its fascination.

That said, this is hardly uncharted territory. Many great snappers had access to the Fab Four’s limos, hotel rooms and backstage areas. And there’s A Hard Day’s Night, Richard Lester’s still amazing film, which turned the whole thing into instant modern mythology even as it was happening. If, like very many, you’ve lapped up every TV documentary, book and magazine article on this subject and have entire sequences from A Hard Day’s Night burned into your consciousness – and are still, of course, planning to see the show – you may wonder what new insights can possibly be revealed.

Indeed, the advance intelligence that McCartney is a pretty good photographer by any standard won’t come as a surprise. He was always the most surprising Beatle. Where John was the moody troubled “genius”, George the mystical muso and Ringo the slightly grumpy ordinary bloke, McCartney was the cheerful, garrulous mop top with hidden – or actually not so hidden – depths. While the others retreated to mansions in the stockbroker belt at the height of their fame, Paul lodged with the family of his girlfriend Jane Asher in the posh part of London’s West End and got into experimental music and far-out literature. He was the Renaissance Man of the group, or, as the pop artist Peter Blake once put it to me, its “intellectual dandy”.

The exhibition’s first images give us a candid look at life on the road as the Beatlemania phenomena builds rapidly around them. McCartney’s newly acquired Pentax camera – lightweight and easy to use – captures the various band members relaxing backstage, their support bands, such as Peter Jay & the Jaywalkers – anyone remember them? – tuning up. There are friendly portraits of Cilla Black, Dora Bryan, the Liverpool actress who had a comedy hit with “All I Want for Christmas is a Beatle”, and quite a few of Harrison’s parents, who look a friendly couple. This is good, fresh, everyday photography, though not so remarkable. Quite a few of the early images are slightly out of focus as McCartney gets used to the camera, and the large number of appearances from McCartney himself attest to the fact that many of these photographs were taken by members of the band’s entourage – and they’re pretty good too.

These early images provide only slight new insights into a time and place that will be familiar territory for most gallery-goers. Shots of band members coming on and off stage could pass, at a glance, for stills from A Hard Day’s Night. Indeed, the closer you feel to the developing Beatlemania moment, the harder it is to imagine why it seemed so world-changing at the time. A bunch of very ordinary lads wrote some good songs, took them on the road, got massively mobbed and made a lot of money. This basic cash-cow template has been followed by so many subsequent acts, from The Monkees to One Direction, it’s hard to imagine that this could have felt like Day One in the birth of a new Britain, even a new world.

But a section on the Four’s appearance on the BBC TV panel show Juke Box Jury gives a great flavour of why it felt exactly like that. The entire country seemed to come to a standstill to hear the band’s sardonic pronouncements on the latest pop releases – which we hear on audio. McCartney’s rapid-fire snaps capture the preparations for an event when the band’s deadpan piss-taking of the records, the programme and themselves – all in flat Scouse accents – achieved the character of pop performance art, and was seen by millions.

But it’s in a section on the band’s first visit to Paris that McCartney’s photography and the show itself move up a gear. A great deal of the rock’n’roll lifestyle is simply hanging around or waiting to be shunted between hotels, airports and venues, and documenting this otherwise empty time becomes a real project for McCartney as he becomes more expert with his camera, exploring “angles, composition and light” as he recalls in the wall text. The shots of massed photographers, slightly surly looking crowds along the Paris pavements and of billboards bearing their names, all in lustrous early Sixties black and white, bring to mind French New Wave films of the time. Indeed, the idea of the lens of the subject – McCartney and his bandmates – looking back at the massed lenses of the paparazzi feels like a clever-clever conceit from some Jean-Luc Godard film. But it’s good old Macca, the lovable Scouse mop top, who’s very consciously pursuing it here.

The images in this vein just get better as the band reach New York. “Photographers, Central Park, New York” (Feb 1964), with two snappers’ lenses shoved right up to the car window, is a real classic.

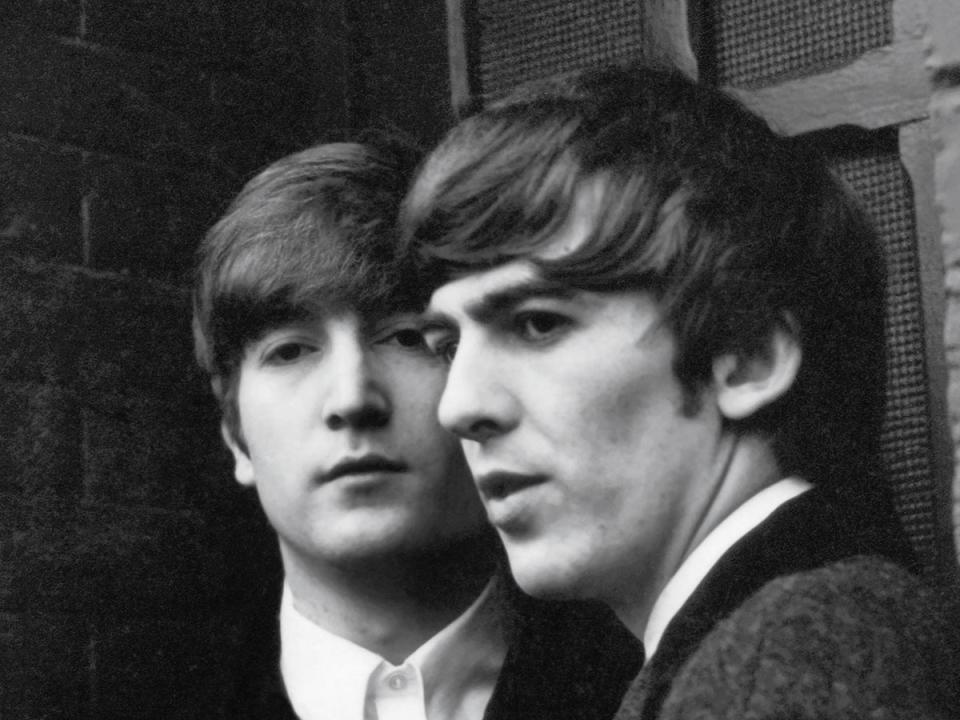

McCartney’s portraiture improves rapidly, too, with practice. A soulful shot of Harrison deep in thought, “George Harrison on a Paris street” (1964), is one of the best pictures ever taken of a Beatle – and there’s plenty of competition. But the most revealing pictures here are, in many ways, some of the least noticeable: candid snaps of McCartney’s creative collaborator, alter ego and nemesis John Lennon. Lennon is at once the group’s great individualist and the one who reveals himself least in photographs. His slightly flat features give little away. Yet McCartney’s searching lens manages to capture nanoseconds of haunted vulnerability, as Lennon, miles away behind his glasses, shows a tendency to move his fingers, childlike, towards his mouth. As McCartney says, “We were a tight-knit group, so only one of us would have been able to get these kinds of photographs.” Considering they were taken over the course of barely a year, these images are a remarkable achievement.

National Portrait Gallery, from 28 June to 1 October