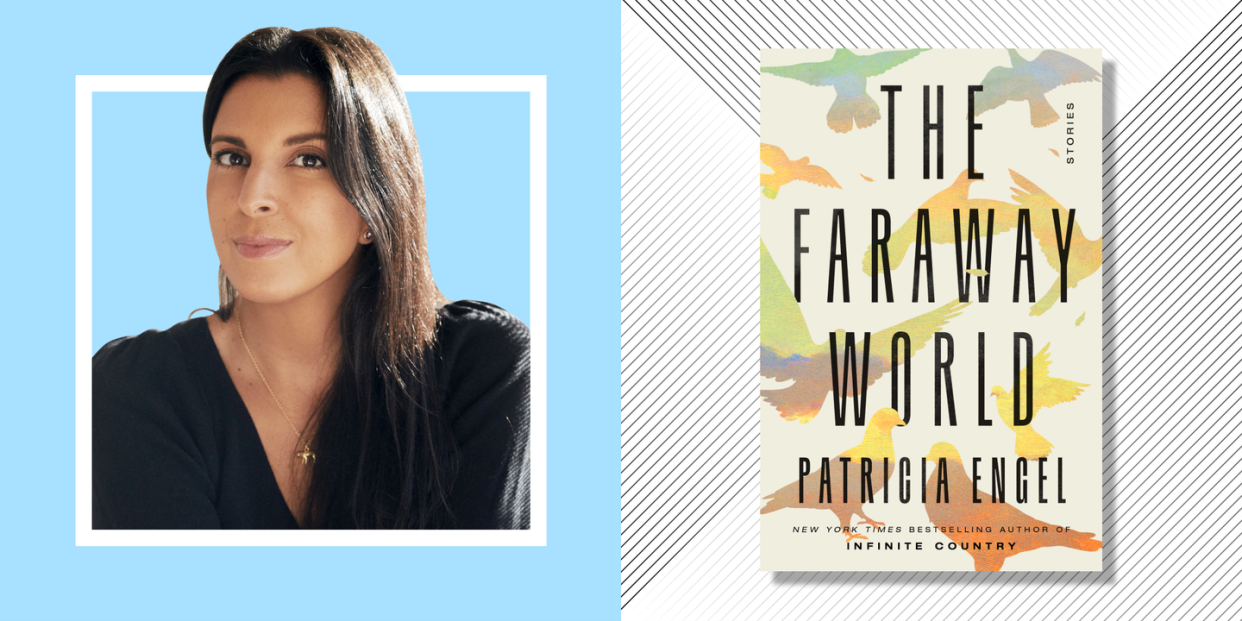

Patricia Engel's Short Story “Libélula,” from Her Collection “The Faraway World”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

The first time we met you asked me to tea. It was at an Italian bakery not far from where you lived. You ordered for me. A cappuccino and a chocolate pastry. You didn’t want me to see your home yet. You confessed that later, months after you’d offered me the job to clean and supplement care for the baby you planned to have, though you said you would also hire a nanny. You complimented my sweater and my nails. You asked if I painted them myself, and when I told you I did, you said you’d pay me extra to do yours too.

We were the same age, but you spoke as if much older, as if I were a child and you were my educator. You explained the neighborhood. When you showed me around your apartment a few days later, you presented your park view as if it were a blue blood family crest. Your husband was traveling. I would not meet him for several more weeks, but he participated in our conversations when you told me he liked his boxers ironed, his collars pinned, his shoes sorted according to hue. You’d met in infancy, you said. Your families were old friends. You came to this country together for university and were permitted to live together with the understanding that you’d marry after graduation and you both complied.

In another life, I might have also been your maid back in Colombia. You might have inherited me from your mother, who employed my mother, or I might have arrived at your door referred by one of my friends who was employed by one of yours. I also came to this country with a man who pledged to marry me. In the end I was the one who escaped vows and he returned to Medellín because this country did not deliver on its promises. I didn’t say any of this when you hired me. You only knew I’d been employed as a housekeeper for years by a Swiss family on the west side who’d relocated to Dubai. You wanted someone to work full-time, the way it was when you were growing up. Not a once-a-week cleaner as was common around here. You wanted a woman to be there when you woke up, to serve your breakfast on the dining room table and disappear in the evening when your husband returned from work and you would wait for him at the same table in an outfit you modeled for me earlier, asking if it was obvious you’d gained a few pounds. You wanted a ghost, a shadow to move about your home anticipating your every need. A double as loyal as an imaginary friend to accompany you, potentially until your death when I’d be retired and returned to my relatives. This proposal did not offend me because I was raised as you were, but on the other side of such an arrangement, and, as you assured me when you offered me the position, I would be well compensated.

You did not work and felt no shame about it. You were too busy to have a job, you said; you barely had enough time to get the sleep you needed with all your errands and appointments. You’d studied finance, but your husband managed your money and his secretary called sometimes to go over charges on the credit card statements. You gave me cash and a pushcart for grocery shopping. You liked for me to go to the market every day as if we lived in Europe, you said, or back home where the produce was fresh and not waxed and lifeless as it is here. I cooked for you though you complained my recipes were too simple. Beans, you said, were peasant food. You bought me cookbooks. You positioned me in front of the television to watch instructional programs of famous chefs. I was not a very good student and rotated the same few dishes I’d mastered every week. But I did your manicures and pedicures, massaged your shoulders, and brushed your hair as you told me your husband was a reluctant lover, that his mother secretly despised you and you secretly despised her; that if you didn’t have a baby soon you feared he would leave you and you’d have nowhere to go but back to Colombia and you would rather die than return to your family without a husband or a child to show for your time abroad. I listened with the devotion of a nun and so you let me stay.

I came to this country at twenty-three. The same year you married. My boyfriend was already here, working as a doorman in Long Island City. We rented an efficiency near St. Michael’s Cemetery, and I found a job cleaning tables and counters in a cafeteria. When things turned bad with him, I went to live with a friend on Lamont Avenue. She was the one who told me about La Palmera, the dollar club on Roosevelt. Everyone does it at some point, she said. Harmless, fast cash. All I needed to do was wear party clothes and high heels and sit along the wall with the other women until a man asked me to dance. Two dollars a song. Forty dollars if he could commit to a whole hour. The men were mostly day laborers, rough-handed, often still in their work clothes. They would ask me to dance, and it was like in the old days you hear older people describe when everyone was well- mannered, when a dance and holding hands had nothing to do with sex. This is how it was until one of those men became aggressive or obsessive with one of the ladies, which happened from time to time, confusing payment with romance.

There were security guards who looked out for us. The truth is I had no bad experiences there. It was a safe place for me, dark and full of lonely strangers who felt moved by human touch and conversation over cheap beer and watered-down cocktails. These men spoke of wives and children they left in their countries, wondering if there would ever be enough money to bring them over or to justify the end of their American experiment and go back home themselves. Sometimes the men didn’t pay, so I started collecting my cash before going to the dance floor the way a prostitute would do, though I did not see dancing for dollars as prostitution. Still, it was nothing I would ever tell anyone, even my mother, and especially you. But I came to see time as the measure of a song on a scale of money, and in my future jobs, I’d see my tasks as a series of tunes, the washing of dishes, the folding of laundry, the making of the beds equivalent to a set of salsa or bachata.

I ran into a friend at El Mundo supermarket who told me about a studio share available in Manhattan. The apartment belonged to a woman who worked as a live-in nanny and used it only on weekends when the family didn’t want her around. I could sleep in the bed all week, and take the sofa on Saturdays and Sundays. She was the one who set me up with the family that led me to you. When I told you I lived up on 177th Street, you made it sound like Canada. You could not believe I took two trains and a bus to reach you all before you woke up each morning. You hated the subway. The bus was even worse. You could tolerate taxis if your life depended on it, but your preferred mode of transportation was a chauffeured car from the service your husband’s company supplied without end. When you had the first miscarriage, you preferred to wait for the driver instead of taking one of the dozen yellow cabs that passed in front of the building. You folded into yourself. I held you by the elbow so you wouldn’t spill to the ground. I’d helped you pad your underwear for the bleeding. You whimpered in pain. Your husband said he would meet you at the doctor but it was two hours of you splayed on the table releasing tissue before he arrived. You asked me to stay with you. You held my hand and your eyes found mine when they weren’t pressed shut. The doctor came in between other patients. Better to be here than in the hospital, he said. If you were lucky, your body would complete the process naturally and you wouldn’t need surgery. When he stepped out you repeated his words. If you’re lucky. I hated him for you, and your husband even more when he did show up, for the way he kept turning from you, checking his phone, groaning as if his body were expelling a life and not yours.

When we took you home, you asked that I remain in your room with you and not your husband, who did not protest. You begged me to stay the night. You would pay me extra, you said, and I told you there was no need. I stroked your forehead as you fell into the kind of sleep I know was not restful. You were in another dimension, one I recognized from the time I lost a pregnancy, though for me it was a relief more than a sorrow because the man I was with at the time did not want to be a father, but the ache was just as morbid, the void, undeniable. In the morning your husband found me sleeping on his half of the bed. I stood up, embarrassed, but he did not look my way; to him I was as invisible as ever, his wife’s little doll, I presume. He kissed your brow and apologized for having to go to work. You did not respond. Your eyes said you loathed him. We both did. That morning, the room cast in gray light, we were the same.

Your new home was a narrow brownstone with a designated servant’s quarters behind the kitchen. You told me I would have my own bathroom and private entrance. You didn’t expect I’d hesitate to leave my current living situation uptown for your address on the southeast end of Central Park. You did not know I was in love at the time with a man who lived a few doors down from the apartment I shared with the other woman. He lived with his wife and her mother and his mother in the sort of communal misery that can only flourish when you have a family you so love. I was careless and forlorn in the way that the men who paid for dances with me were, so eager for a soft touch, for eyes that did not judge. To him, I was just another solitary woman in the neighborhood. We slept together many times at my place. He was quick and generally took me from behind, then went home to his family. I did not know how to stop desiring him, so when you proposed that I come live with you and that you would increase my pay accordingly, I agreed.

You were hopeful you would get pregnant again, even as months passed without a sign. You changed doctors many times. You gave blood and took pills and started diets to help your fertility. Women came to the house to massage and push pins into you, to teach you poses and hypnotize you into motherhood. You kept a thermometer and a calendar by the bed where you marked certain days with a purple pen. And then you were pregnant. You showed me the pale line on a plastic stick, and for the rest of the day urinated on several more and displayed them on the counter to show your husband when he came home. Over dinner you asked him why he didn’t seem happy. He wanted to be cautious, he said. He was afraid you’d both end up disappointed like last time. I was in the kitchen cleaning when you met me by the counter with a wet-eyed stare. My bedroom was two flights below yours, but the house was old and I heard your fights through the vents, how you pleaded for some emotion and how he called you irrational, demanding, and depressing to look at. The next day, the pink streak on the sticks was gone. The phantasm of a pregnancy departed, and you moved about the house stiffly. You stood at the doorway to the room you’d outfitted with a crib because one of the experts you hired told you it was the way to manifest your desired outcome. I put my hand on your shoulder, and you turned into me so that we were embracing in a way I did not expect and never would have initiated because I know such intimacy cannot be tolerated in a workplace, even among those employers who claim their domestics are like family. But you held me, and I felt the absence of your mother and your sisters and my mother and my sisters, and when you finally pulled away you apologized as if you’d done something terrible and went to your room.

That night I was in bed watching the television you gave me as I did most nights. You had all the premium Spanish channels, so I could keep up with telenovelas and programs my mother was watching back home and we could text each other about it during the day. I remember we were watching a true-crime series about a group of rich teenagers who murder a lower-class schoolmate. It was representative of all our country’s injustices and inequalities, my mother said. I preferred these shows to ones with romantic plotlines that only made my body feel hungrier and more abandoned. That night’s episode was to be of the courtroom trial. I was looking forward to the prosecutor’s opening remarks. But then the door opened and your husband showed his face, put his finger to his lips, and stepped through. I pulled the blanket over my breasts, which hung braless in a T-shirt, and since I was in my own room, I didn’t bother wearing pants, but your husband could not know this. I asked if something was wrong. I thought he would talk about you, ask if we could plan a special surprise to cheer you up. Maybe he had an idea to take you on vacation or on one of his work trips like you were always begging him to do. He watched me, and I noticed he was growing hard, as if by the wind, and I didn’t know what to say or do, and I have no way to explain what happened next; I can merely tell you the facts, which are that he came to my bed without speaking, pulled the blanket off me and saw only my underwear separating my skin from the sheets and quickly shoved his hand under the fabric and into me. When I said your name, he answered that you were asleep, so sure that I would not resist beyond worrying you might discover us. The next morning, I served you breakfast at the dining room table with a fresh rose in a bud vase beside your water glass, the way you required, and you could intuit no difference in me and I remembered the ways you did not see me at all, left your clothes strewn about your bedroom, towels tossed to the tile, your long hair filling every drain, with no consciousness for the energy it took to bend for you over and over, to expunge your filth. In your mind you were perfect, and I helped offer that notion to those who entered your home, to those who heard you talk about all the care you put into your household upkeep. When a magazine came to photograph your home, you did not show them my room and told me to leave the house for the afternoon. Americans don’t understand how we are about employing houseworkers, you said. They think everything is exploitation. Then you wanted my opinion. You like working here, don’t you? We treat you well, don’t we? I nodded. Of course, I said. You didn’t insist that I call you señora or doña. You said I could call you by your first name and when you took me around the city on your shopping excursions, you referred to me as your friend to salespeople and waiters when we stopped for lunch, even as you criticized my table manners or corrected the way I spoke, mocking my idioms. You gave me clothes you no longer wanted even if they still fit you and were like new. In fact, on many nights when your husband came to my room after you were sleeping, I was wearing a nightgown that had once been yours.

You never thought me beautiful, and why should you? I am not. When my boyfriend was unfaithful I learned the other woman doesn’t need to be prettier, she only needs to be different. You noticed your husband leaving your room some nights and mentioned it to me. You thought he was going to the den to watch television or to play computer games since he knew the screen light bothered you. You were deep into your fertility treatments and cried most afternoons and iced your face to depuff before dinner. You went through many cycles that produced no good embryos. You were one of five children. Your parents, each one of eight. You didn’t know what you did to be cursed with unwilling ovaries and a bully uterus. You asked me to go with you to see a brujo uptown who wore a robe and sat on a golden throne and said you would have four pregnancies. When you replied that you’d already miscarried four times, he added nothing more.

On the way home we stopped in a church and you asked a priest sweeping the altar for a blessing, and he gave me one too. We dipped into the park before crossing the avenue to the house. The weather was calm and bright, and the city was curiously quiet. We lay on the grass like schoolgirls, and I thought of the years before I understood I would have to work every day in a home and that meant I’d never really have a home of my own. How strange the grass felt in this city, so different from the grass and earth I felt under me in my youth. I asked if when you came to this country for university you knew that you’d stay here forever. You said you never thought so far ahead but you are a citizen now, so that must mean you are an official immigrant. Not me, I said. That word never seemed to fit even though I’d already married for papers and divorced and was as much a citizen as you were. I thought of myself as a satellite sent into orbit and when I’d return to my base on Earth was yet to be determined, though inevitable. Till then I’d float in diaspora, circling my planet until I went home or went dead in outer space.

Sundays I typically went to see old friends in Jackson Heights. You encouraged me to socialize with the other housekeepers and nannies of our neighborhood so I wouldn’t have to go so far for camaraderie, but then I overheard your mother warn you on a video call that it’s not good for maids to talk to other maids because they start comparing notes and next thing you know, you have to give your maid a raise three times a year. I knew I was already overpaid compared to other women who worked in the area. You did not deduct for my room or for providing food. I finally paid off my marriage debt and sent most of my salary to my mother, who was able to move into a new apartment. She wanted me to come home for a month at Christmas now that I could afford a ticket, but you said you would die without me, and besides, you needed someone to watch the house while you went skiing, so I postponed. You were filling out paperwork for adoption. You had an idea that you could adopt from Colombia and maybe it was your fate. Your husband did not want to parent someone else’s child. It would be your child, you said. I heard it through the vent. I heard it again over breakfast and at dinner. Still, you worked for months on those forms. When your husband came to my room he wanted only to please me. I pretended he was not your husband and this was not your house and I was not your maid or empleada or muchacha or mujer de servicio as you would call me if we were in our own country. Perhaps your husband thrust his virginity upon one such woman in his childhood home. At night I thought of none of those things. It was the only way to forget the songs in my head, the infinite loop waiting for something to change in my life of waged companionship and knowing it would not.

I left you because I could not stand to see your dejected face or the way I would make it worse. If I think hard, the moments when I saw you content are few. The day when we lay together in the grass and you marveled at a dragonfly that landed on your finger, said it reminded you of the ones floating around the grounds of your family’s country house as a girl, that afternoon choosing you over all the human bodies in the park, proclaiming it a spirit marker, an omen of good things to come, and I did not dare tell you that in the barrio of my youth, a libélula touching your skin meant exactly the opposite. Or when I saw you dress for dinner each night with hope that somehow your outfit would draw your husband’s soul closer to yours. If you saw me like this, it would destroy you, and I am not a destroyer, so I had to leave you. I waited until you were out with a friend for lunch. The friend you often got drunk with in the middle of the day or at night when your husband was in a different time zone. The European diplomat’s wife. You envied the lifestyle her husband’s career afforded. The wide embassy town house, the staff of six. You smoked marijuana and did cocaine with only her, you said, because it didn’t feel as trashy. I loved handing you off to her because it relieved me of caring for you for a few hours. This day, when you said goodbye and gave me instructions for what to make for dinner, I wished you well and hoped I would never see you again.

When you came home, instead of calling for me to guide your drunken steps up the stairs, to prepare you a hangover preventative, or to ask me to lie to your husband about why you were feeling tired and ill, you would find the house empty. There would be no dinner waiting for you and your husband. You both might search the house, taking inventory of your valuables. The only things in my bag were my clothes, none that you gave me but what I brought with me when I moved into your lives, some money I saved, my marriage and divorce papers and my passports.

I rented a room in Corona from a woman I knew from La Palmera who still danced by the song. She told me I could come too, make some cash like I used to, letting men press their cheeks to mine, but I showed her the soft curve beneath my navel. It’s okay, she said. You don’t have to drink. Just tell the bartenders to fill your cocktails with juice instead of liquor. Ladies do it all the time, and some dance till their third trimester. I still hadn’t figured out where I would land. An American baby, my friend cooed. She didn’t ask who the father was. I never would have told her. I’ve seen enough news programs to know disadvantaged mothers can have their children taken away for putting on a diaper crooked. I had a vision of you mothering the life inside me. And still I did not panic, even as I considered a future where you and I might run into each other in the park or on the avenues we once walked together, me carrying your packages, and you would see the child in my arms, notice a resemblance, do some math, and understand the origin of my motherhood. I would have something that could never be yours.

When my mother asked, I told her the truth that my employer’s husband got me pregnant and she let out a revolted sigh but acknowledged that sometimes these things are unavoidable, and such bastardry is so traditional in our hemisphere that it’s secured a role in all the classic telenovelas. I found work in a restaurant and back at El Mundo I was introduced to a friend’s cousin who manages a flower supply. He asked me to ice cream, to a movie, to pizza, and taught me the scientific names for a dozen species of Colombian magnolias before I admitted I had a baby due in a few months and he said he would still like to see me. He was raised in Sincelejo. He has memories of his father hitting a man with his car on a country road and not stopping, even as the children saw in the rearview mirror that the man had been killed. The trauma made him righteous and repentant. I will be your child’s father, he said.

And then you are before me, not in the way I envisioned but close. We are at JFK at the gate waiting for our flight to Medellín to depart. I am with my husband and son. You are with your husband and daughter. I will never know how your child came to be yours, and you will never know how mine came to be mine. Your husband doesn’t even know it, shining ignorance in the way he shakes my husband’s hand and congratulates us on our handsome family as if we are old friends, as if the past was swept away by your new maid’s broom. My husband welcomes his good wishes, believing my son’s father some dishonorable vanished lover.

You hug me, and I feel you warm against my neck. I have missed you, you say. You forgive me, you add, and I wonder for what, since I have not said I am sorry. Early in my employment I tried to quit after you yelled at me for using the wrong liquid on your wood floors. I was already standing at the elevator holding a bag with my few things but you followed me saying everyone makes mistakes and convinced me to stay. I later heard you on the phone with your sister, laughing about how I’d made a show in trying to leave as if I weren’t replaceable, as if there weren’t ten other women who could do my job for cheaper and with less of an ego. She’s so humble yet so prideful, you’d said. And still I loved you. And you loved me. In an incomplete way, of course. Love’s imposter twin that still feels real because it has become constant, ordinary, routine. Love doesn’t need to be exquisite for it to be true. I learned this with my husband, who is faithful and never punishes me with indifference.

You give me your parents’ address in Medellín and say to call so we can get together during our vacations. You’d love to have us over for lunch and show me where you grew up. You could even send their driver to pick us up. We watch your family board ahead of everyone, and when it’s our turn, we edge through the aisle and see you in your first-class seats, so focused on managing your champagne flutes and the child on your lap that you don’t notice us pass. They seem like nice people, my husband says when we take our own seats behind the wing. We don’t need to call or see them, I say. He doesn’t ask why. At the luggage claim, your baby is crying, and I am surprised you haven’t brought a nanny with you the way you always declared you would to travel. Your baby seems too heavy or your arms too weak. Your husband takes her, holds her close, and she is soothed. Your bags are the first to appear on the conveyor, adorned with priority tags. You wave to us as you make your way to customs and disappear.

I will think of you often for reasons I can’t explain. When my son is five, already in school, I will take the train to Manhattan and sit on a bench along the park across the avenue from your house, impatient for proof that you still live there. I will wait for hours until you emerge with your daughter on one hand, your purse in the other, wondering if I will catch your gaze, but you only look ahead, and then you are gone and I never look for you again.

The Faraway World: Stories

amazon.com

amazon.comYears later, a vision comes to me as real to me as my own breath: you and I sitting on that plane approaching our shared birth city, my awareness of you so close that I smell your perfume. I recall how a similar jet crashed into the mountains surrounding our valley just a few months earlier, killing everyone on board, the tragedy of the year. I imagine the passengers’ fear. I read somewhere that panic comes from lack of preparation. That’s why on airplanes they give emergency instructions every time as if it’s the first, remind where the escape routes are, and why when you enter a new space you should always locate the exits so a fire doesn’t catch you by surprise. Forget instincts, the article said. Survival requires practice and a plan. I close my eyes and see us spiral through the clouds with our families, the rabid rippling Andes biting the side of our plane, leaving no survivors. You and I swallowed and returned to the soil and rock that made us, erasing time and the lives we made in the other world, as if we’d never once dared to wander so far away.

Copyright © 2023 by Patricia Engel. From the forthcoming book The Faraway World, by Patricia Engel, to be published by Avid Reader Press, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

You Might Also Like