It’s Past Time to Get Rid of Fat Suits (the Same Way We Did Blackface)

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

There’s no doubt about it—the representation of marginalized people onscreen has vastly improved over the past decade. These days, we get to have Quinta Brunson pulling at our heartstrings as an earnest and overworked public school teacher, Michelle Yeoh kicking ass as a multiverse-bending superhero, and Billy Porter as the genderless fairy godmother of our dreams. Which is why it’s such a disappointment that in one arena, there’s been a marked lack of progress: body diversity.

With a few rare exceptions, the most visible depictions of fat bodies on television and film position them as slovenly, incompetent, or objects of mockery and pity. Often, those depictions don’t even include actual fat people. Instead, they use thinner actors in fat suits to perform roles that further the idea that fat bodies are to be ridiculed.

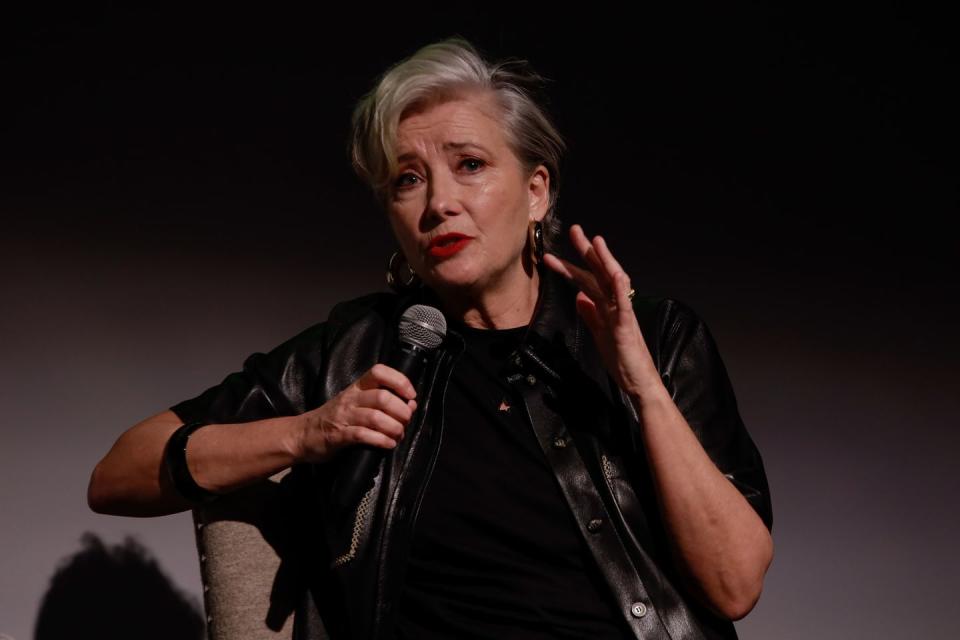

At the end of 2022, there were two major films in which characters don fat suits. Both star well-loved actors: Brendan Fraser in The Whale and Emma Thompson in Matilda the Musical. In the first, Brenan plays a 600-pound man who is largely confined to his couch—a role that may earn him a Golden Globe on Tuesday night. In the second, Thompson plays Matilda’s domineering villain, Miss Trunchbull. Both associate fatness with misery and disgust, casting bigger bodies as a moral failing.

Frankly, after years of these tired depictions—from Courteney Cox on Friends to Max Greenfield on New Girl—it’s time to say it: Actors who wear fat suits on film should be subject to the same scrutiny and condemnation as those who have or continue to appear in blackface. And while it may seem like a stretch to compare the two, there is overlap in their social functions: to mock and diminish people who are already marginalized to begin with. It begs the question: Why do we continue to heap acclaim on actors wearing fat suits when we know that stories about any group of people should include buy-in from them?

Anti-Blackness and anti-fat bias are, of course, not the same. And there are meaningful differences between the practice of putting on a fat suit and using skin-darkening makeup that mean they cannot be seen as equal. But it is helpful to understand how both are used to further ostracize people for simply existing.

First, a bit of history: Professor Alyssa Lopez, a scholar of early 20th century African American history, says blackface was used in early films by both Black and white actors. For white actors, it allowed stories to include depictions of interracial intimacy and closeness—such as a Mammy tending to a white child—without needing white actors to interact with Black ones.

But with Black actors, blackface was used to perform “authenticity” for white audiences who believed that the darker a character was, the funnier they were. Lopez says that part of the process is erasing the talent of Black performers. “There’s a diminishing of Black actors beyond the comedic. A disbelief that Black professionals actually existed or that they can only be funny,” she says. “It’s saying, ‘We know what Blackness is. We don’t need authenticity. I don’t need to involve you or pay you.’”

It’s the same attitude actor Guy Branum has encountered as a fat performer in Hollywood. The practice of using fat suits presupposes that there are no capable fat actors like him who can fill these roles. “It’s something that cannot be disproven until people are given the opportunity to prove it,” he says. “I would have loved the opportunity to audition to play Baron Harkonnen in Dune. What a great role.”

But on The Whale—a mostly tragic tale where Brendan’s character is plagued by struggles that the film suggests are of his own making—Guy demurs. “I wouldn’t want to be part of it, because it wouldn’t be the same movie if you had an actual extremely fat gay person there. Because then we would have had to ask questions about his humanity.”

Guy also observed that in the case of both blackface and fat suits, Blackness and fatness are treated as things one can simply put on or take off at will. It’s a scenario that lends itself to indulging in offensive caricature. “There’s something so strange about seeing somebody spend six hours in makeup to look like me, for a role that I would never be considered for,” he says.

And in both cases, the truth of a marginalized group’s experience is ignored in favor of narratives dreamt up by a socially and politically dominant group. Fat suits allow thin people to create fictions about fat people’s lives for the benefit of other thin people. Then those same stories are used as a justification to discriminate against them.

Confoundingly, fat suits are also a way to reward thin people for attempting to empathize with fat people, according to Aubrey Gordon, cohost of the podcast Maintenance Phase and author of the new book You Just Need to Lose Weight: And 19 Other Myths About Fat People, both of which debunk fatphobic stereotypes. Where a fat person is rejected for their body, a thin person is met with acclaim for gesturing at the experience of fatness.

“It’s a reassurance,” she says. “You did this, and we’re rewarding your effort because we know you’re really hot.”

Gordon noted that for the actors who wear them, fat suits have graduated from being a tool of comedy à la Shallow Hall or The Nutty Professor to an indicator of prestige, as in American Crime Story: Impeachment, in which Sarah Paulson wore a fat suit to play Linda Tripp. Gordon says this shift is “less about mobilizing laughs and more about mobilizing pity.”

“The point of these stories is making thin people feel like their bodies are accomplishments—making them feel like they can judge fat people but still feel like they understand us and feel okay about laughing at fat people’s expense,” she says. “It’s reinforcing the one main narrative we have about fat people and fat bodies, which is, ‘You did it to yourself. I can pity that or laugh at it, but I’m not going to empathize with it. I’m not going to hear you out or listen to your stories.’”

In The Whale, Brendan’s Charlie is in mourning the death of his lover. He spends his days teaching a creative writing class remotely with his camera off and sparring with his hostile daughter. The film’s opening scene depicts Charlie masturbating so furiously that he nearly has a heart attack. And throughout the film, despite the many times he is shown eating, at no point does he enjoy food or savor his meals. Instead, he swallows them so quickly that he neglects to chew, and in one scene, he nearly chokes. Charlie has no existence outside of his fatness.

“He never gets to have pleasure. He never gets to have charm,” Guy points out. “This doesn’t imagine a life for Charlie that is any more than the sense that he’s disgusting and sad. It doesn’t even contemplate that this man who is a professor—who thinks about art all the time—has no art or beauty in his life.” Even when stories about fat people suggest interiority, they lean hardest on reductive tropes.

But as terrible as The Whale is, Emma Thompson isn’t off the hook either. To Gordon, her turn in Matilda is especially disappointing given her work in the awards contender Good Luck to You, Leo Grande. On the press tour for that film—in which she appears naked—Emma spoke candidly about baring her body onscreen in her 60s and accepting her body for what it was.

But her role in Matilda undermines that enlightened worldview. Miss Trunchbull is a former Olympian, an imposing woman who is rough and cruel. As with many stories aimed at children, the story reduces virtue to simple binaries. Thin people are good, and fat people are bad. But Miss Trunchbull is also portrayed as masculine and rough. Her fatness negates her femininity. Her body is used to support the argument that she is evil.

“Within days of that [Leo Grande] interview, we got the first press photos of her in a fat suit as Miss Trunchbull, who is a famously abusive character—famously a fat monster,” Gordon says. It was a clear message that fat bodies were not included in Thompson’s vision of body positivity.

Meanwhile, Brendan, who retreated from Hollywood 20 years ago after he said he was assaulted, has received near-universal praise for his comeback role in The Whale. And while Brendan no longer cuts the same figure as he did in his days playing Tarzan, he is nowhere near as large as his character. The “transformation” is a tried-and-true Oscar pathway. Unfortunately, as much as we all root for him, it’s a pity that this is the role in which he makes his return.

According to Gordon, as a culture, we are slowly approaching a clumsy “transitional stage” around anti-fat bias. But, as these recent works show, we’re not quite there yet.

The evolution of how blackface is regarded in entertainment is a useful case study: Into the 2000s, blackface was still considered edgy and acceptable in comedy. But in the summer of 2020, many television shows like Community, 30 Rock and The Office took the added step of removing episodes containing blackface from streaming. It took a political flashpoint to get the message across, but it did happen.

We know, undeniably, that pervasive depictions of fat people as victims of their own ill-discipline trickle out into the real world and influence the way others see and treat them. We may not be able to solve anti-fatness overnight, but we can stop the flow of harmful media portrayals by doing away with this offensive and unnecessary practice. And we need the artists and creators who continue to propagate those narratives to be held accountable.

Fat actors deserve to work and embody roles that reflect the experiences of their lives, and fat people deserve to see themselves onscreen. So from now on, Hollywood needs to commit to the bit.

Go big, or go home.

You Might Also Like