This Paralympian Defined Her Own Future. It Includes Podiums for Others Like Her.

This article originally appeared on Outside

Scout Bassett learned an important lesson from an early age: you have to create your own luck.

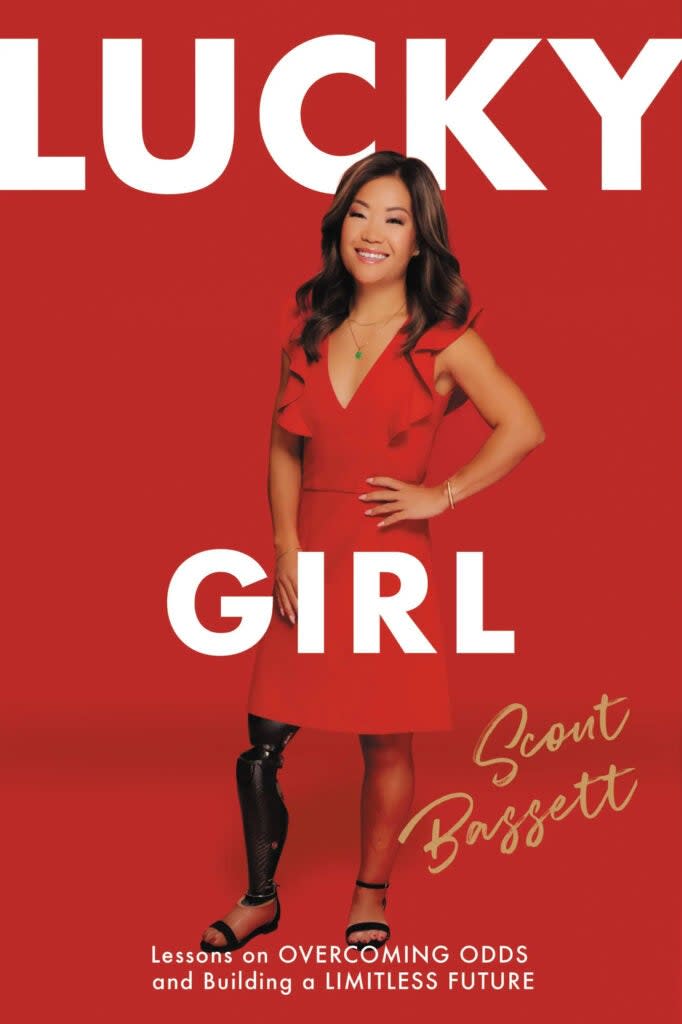

Born as Zhu Fuzhi ("Lucky Girl" in Chinese), Bassett had to endure years of life's cruel irony in her name. As an infant, she survived a fire that resulted in the loss of her leg, as well as the early abandonment by her biological parents.

Part autobiography, part self-help, part social critique, Bassett's new book Lucky Girl, Lessons on Overcoming Odds and Building a Limitless Future offers a candid view of her life, athletic career, and the seemingly insurmountable obstacles facing athletes with disabilities, especially female athletes. Bassett's intention of this book was to help "position ourselves to be overcomers--to be champions...to have the fortitude, the grit, the strength, and the mental toughness to do just that."

Surviving Trauma from Childhood to Adulthood

The book tells Bassett's personal journey from a poverty-stricken Chinese orphanage, to a small northern Michigan town, to the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), to the Rio de Janeiro 2016 Paralympics, and to the heart-breaking miss of making the 2021 Tokyo Paralympics team.

Bassett takes a straightforward narrative writing approach to the story of her childhood. Her earliest memory was tainted with hardship and abuse in the orphanage: living on a bowl of rice every day, sleeping in a narrow cot with another orphan, surviving abusive disciplinary acts such as waterboarding. The children never went outside; Bassett never even saw a housecat until after her adoption--or any animal for that matter.

Following her return to China as a Paralympian after the Rio Games in 2016, Bassett was thrown back into her childhood trauma. The experience of seeing that the orphanage had not changed much--the same rice for the children, the same permeating urine smell in the building--left Bassett with panic attacks long after her return to Los Angeles.

Discovering Belonging Through Running

Being adopted into a conservative Christian family in northern Michigan was her first salvage, though it didn't solve her problems of feeling like the other. Bassett never knew what a school was, let alone being the only Chinese student in a majority-white school and the only student of disability.

"Growing up and being ethnically Chinese, disabled, and adopted, I can't remember a time when I didn't feel like an other. This dynamic was most obvious at school, with my peers, and the sports teams I was on."

Even after arriving at UCLA, she felt she wasn't fully accepted by some Asian American students. "By the time I got to college, I hadn't spoken Chinese in over a decade...I was raised by a white family...For my roommate, I was too culturally white to be Asian," she writes. "Not white enough to be white, mind you...But not Asian enough to be Asian."

RELATED: Des Linden in Her Masters' Era: "I'm Glad I'm 40"

When Bassett discovered running at age 14, it was an indescribable sense of freedom which enabled her to overcome a mindset of victimhood and otherness. "Running was really that transformative for me," she says. "I grew in confidence; I grew in self-belief. I held my head just a little bit higher."

Eventually, through running, Bassett realized that "Being an other is a lonely place to be," and shared a bit of advice: "Don't allow your otherness to lead you to embrace a victim mentality...If you're reading this right now and you feel like an 'other,' here's what I'd say to you: Do not hide. Please, don't hide. Don't mask who you are...Your path is not going to look like everybody else's, but aren't you glad?"

Betting on Yourself While Navigating Loneliness

Arriving at UCLA in 2007 started a new chapter for Bassett. Not only was she more exposed to people of all ethnic groups and religious backgrounds--including more Asian Americans and the LGBTQ community--she was inspired to pursue Paralympics once a female coach asked her.

Then came more obstacles: a lack of training facilities and lack of coaches who are willing to work with Para athletes. Bassett was undeterred. She started training herself by watching YouTube videos and showing up before dawn to train on the track.

After graduation from college, Bassett went against everyone's advice and quit her job at a medical device company. She lived in her car and on people's couches to minimize her expenses so she could train full-time. In two years, she competed in the U.S. Championships but came in last. This only made her focus more and double down on her efforts.

The toughest part of Bassett's pursuit was not the demanding physical training, but the prevalent sense of loneliness when choosing a path less-traveled. "The obvious truth is that loneliness is a natural byproduct of life in an orphanage. But what I've learned since is that loneliness is a natural byproduct of life...period...I've felt lonely on varying levels during almost every season of my life since."

Even being on the cover of Self magazine and having an American Girl Doll made out of her own image couldn't cure the everlasting loneliness. Bassett accepted the frequent loneliness and used it to fuel her training. "Sometimes, that might be to remain isolated so you can grind out a skill, learning, or development," she writes.

As Steve Magness writes in Do Hard Things: Why We Get Resilience Wrong and the Surprising Science of Real Toughness, "When we explore instead of avoid, we are able to integrate the experience into our story. We are able to make meaning out of struggle, out of suffering. Meaning is the glue that holds our mind together, allowing us to both respond and recover."

When Bassett found meaning in speaking for others who often feel lonely because of their "otherness," she realized that "training, mentoring, and advocacy have been my answer to loneliness--which now doesn't feel like loneliness at all."

This mindset has enabled Bassett to go from finishing last place at the 2012 London U.S. Paralympic track and field trials to competing as a Paralympian at the 2016 Rio Paralympics. After the setback of missing out on the Tokyo Paralympics, she then staged a strong comeback of winning the 100-meter at the 2022 US Nationals.

Building a Legacy on and off the Track

Bassett is unafraid to offer a critical look at the overall lack of systematic support for athletes with disabilities: lack of coaching support, lack of media coverage, and fewer Paralympic events to compete in. It goes all the way to the governing body: Only 4 out of 15 governing positions at the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) are held by women.

But perhaps the biggest hurdles of all are the limited options for Para athletes to continue developing and competing beyond high school. This is one of the intentions Bassett had set up her Scout Bassett Fund, to create a pipeline of Para athletes with adequate financial support. "I'm not talking about a few thousand dollars," she writes. We've had a partner give a very generous donation that will allow us to give five-figure grants to these girls."

Christine Yu has also discussed the profoundly inadequate funding in women's sports in her book, Up To Speed: The Groundbreaking Science of Women Athletes. "On the whole, these institutions (NCAA, etc.) prioritize men's sports over women's sports." But on the Para athlete level, systemic support remains nascent. As recently as January 2014, the board of directors of the Eastern College Athletic Conference approved the implementation of championship sport opportunities for student-athletes with disabilities.

RELATED: Can Women Outperform Men in Sports? That's the Wrong Question to Ask.

Bassett credits track running star Allyson Felix as one of her inspirations with advocacy. "Alyson has been a great role model for me as I've gotten older in my career. She is the person who helped me to see I'm so much more than just an athlete...I'm more than my wins. I'm more than my losses. And Allyson set that example for me to follow,” she says.

In creating her Scout Bassett Fund, Bassett hopes to also create other advocates like Allyson Felix and herself--whole champions on and off the track.

"The main idea behind the Scout Bassett Fund is to allow these young women to train their way into Paralympic contention. But it's also to give these young women a megaphone--to give them a chance to build their own platforms so they can join their voices with mine to fight for equality and to fight for better representation of disabled females on and off the track."

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.