The pandemic changed American education overnight. Some changes are here to stay.

Many thought we'd be out of pandemic education by fall 2021.

We're not.

Schools and parents are still burdened by COVID-19 cases, contact tracing and quarantines. Remote learning has returned in some cases. In others, kids are back to sitting at home without work. Unlike last year, most classrooms are open, but they operate amid shifting health recommendations and frequent fights over masks.

When will school be normal again? Many educators, parents and students look past the health hurdles and say: Never.

"Normal shouldn't be what we used to have, because what we used to have was inadequate," said Paul Reville, a professor at Harvard University who directs the Education Redesign Lab.

Disadvantaged students suffered the most in schools plagued by inertia and caution, Reville said. Wealthier students were more likely to have support outside school, including resources to buy reliable internet and participate in enriching activities that aided their educational and social growth.

The pandemic worsened inequities. Still, Reville said, schools of all kinds have seen "some terrific adaptations during the pandemic that previously we'd been unwilling to embrace."

Experts said some of the 2020-spurred jolts to the system will stick permanently, thrusting education into a more personalized, modernized, responsive space that sets up more students for success through high school and beyond.

More tech-driven classes

Why do most classrooms look the same as they did a century ago, with desks and rows and a teacher lecturing? That observation has been repeated for years, and it took a pandemic to finally change it. Almost every kid got a tablet or a laptop, plus an internet connection – though shortages continue for lower-income students and many who live in rural areas.

Though some schools jettisoned virtual learning in favor of in-person instruction this year, others blended aspects of virtual learning with traditional instruction. Confident in the ability of teachers and students to pivot quickly to remote learning at home, some districts ended snow days and kept kids learning even in the face of natural disasters, such as hurricanes and fires, that would shutter buildings.

Other districts, aiming to meet the needs of students who thrived virtually, created options for students to continue learning online this year.

In Florida, Miami-Dade County Public Schools launched Miami-Dade Virtual School for parents who wanted their children to continue learning remotely, but with more structure, oversight and live instruction than the district's previous online option.

"If anything that we’ve learned over the past year and a half, it's that flexibility needs to be part of our toolbox," Superintendent Alberto Carvalho told USA TODAY in June.

Virtual learning needs major improvements, experts said. On average nationwide last year, students who learned online lost more ground in math and reading compared with kids who spent more time learning in person. Fifty-five percent of parents with school-age kids said online or distance learning caused their child to fall behind, according to a national USA TODAY/Ipsos poll.

Chris Dede, a Harvard professor who studies how learning happens alongside technology, said online school works better for some students and subjects than others. Research must catch up with what styles of online instruction work best and how much time to spend on live teaching versus independent or remote group work.

"Ideally, all teachers will continue to teach in a blended manner, and going online won't be dictated only by necessity," Dede said.

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

Blowing up traditional school schedules

More schools are changing long-held schedules to better accommodate students and promote more steady academic attention. Michigan, for example, allowed schools to adopt a year-round program this year.

Public schools in Des Moines, Iowa, added learning time over lunch to make up for lost hours of in-person instruction. More school districts in Wisconsin requested state approval to start early this school year. In the upper Midwest, schools historically don't start until after Labor Day, because of summer tourism.

Some schools experiment with entirely new schedules to help students juggle education and work responsibilities.

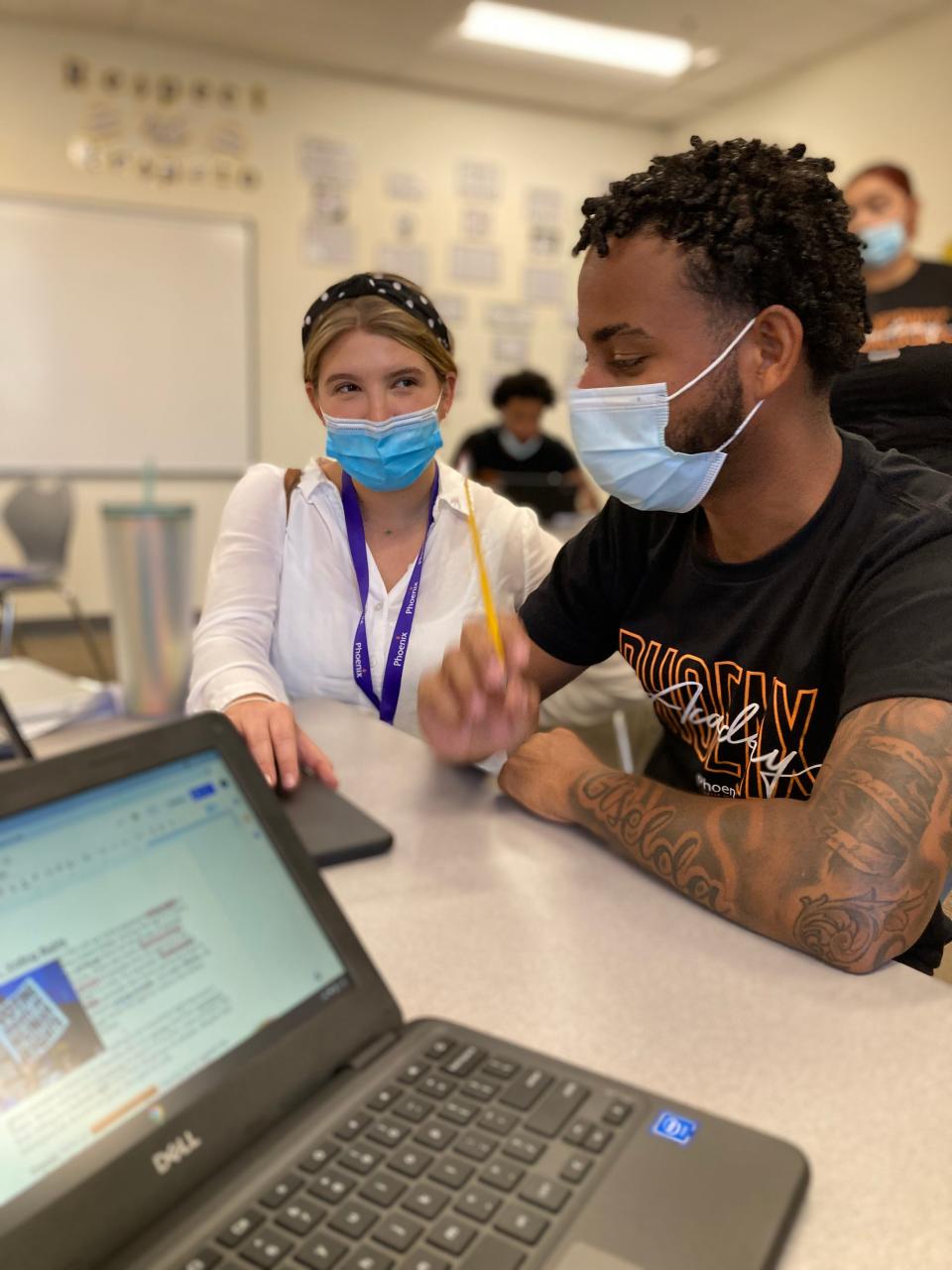

In Massachusetts, Phoenix Charter Academy Network is designed to help disadvantaged youth complete their high school studies. Some students are parents themselves, and about half live in unstable housing, CEO Beth Anderson said.

Many students disengaged during virtual learning last year because they took on full-time jobs or had to juggle family needs, Anderson said. This year, Phoenix Charter Academy Lawrence allows students to attend from either 8 a.m. to approximately 2 p.m., or from noon to approximately 6 p.m. Others may come a few days a week, or even Saturday, in addition to completing work online.

“The pandemic allowed us an opening to do things differently," Anderson said. "We often went from 9 a.m. to 4 or 5 p.m., and we realized we needed to do something different with the schedule. We had to figure out how to build schools around kids."

Stay connected: Subscribe to Coronavirus Watch, your daily update on all things COVID-19 in the USA.

More online-learning pods, micro- and home-schools

Historically, about 90% of children attend public schools. The pandemic compelled many parents to try less traditional options – and some are sticking with them.

About 13% of parents nationwide have a child in private school – religious, non-religious or an online program, according to a USA TODAY/Ipsos poll conducted this summer. Six percent have children in charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately managed. Four percent said their child was in a nontraditional program.

Parents have told researchers they want schooling options that are more personalized and less bureaucratic, said Robin Lake, director of the Center on Reinventing Public Education, a research group at the University of Washington.

Many parents of color who chose online schooling "pods" or home-schooling wanted an experience focused on racial affirmation, Lake said.

"A lot of them said they had wanted to try this for a long time, but they were scared," Lake said. "Would that kind of education hurt their kids' college applications? Could they manage their time?"

Embark Education, a Denver middle school that teaches academics through the operation of a bike shop and cafe, launched in 2019 and has grown to its full capacity: 30 students.

On an afternoon in August, about 10 of the microschool's students wrote fractions and math formulas to figure out an order of burgers, buns and condiments. In another room, students learned the science and proportions of ingredients necessary to make a latte. Kids themselves decide when to schedule their hours assisting at the cafe or bike shop.

"We all like the more personalized learning and attention we get from teachers," said Olive Randall, 12.

Schools finally connect with parents

Teachers and principals have long struggled to develop relationships with parents, particularly those challenged by poverty. Virtual learning finally provided a consistent link between home and school.

Many parents found themselves listening to their child's teacher every day, which helped them understand what teachers were asking of their children.

Connecticut's Hartford Public Schools adopted Zearn, an online math program designed to bring parents into the process of learning.

“We're moving beyond encouraging parents to ask, ‘Did you do your homework?’ And urging them to ask more specifically, ‘How did you solve that problem? How can you justify your solution?’” said Mario Carullo, Hartford's director of math instruction.

"Teachers spent a lot more time explaining how students are learning math to parents," Carullo said. "That’s what’s unusual."

Prioritizing students' social and mental health needs

Almost two years of pandemic living – and dying – has thrust the issue of students' mental health to the forefront of schooling concerns.

More than 1 in 4 parents – 28% – said their child's biggest struggle during the pandemic has been mental health; 37% said making and maintaining friendships was their child's biggest struggle, according to the USA TODAY/Ipsos poll.

Nearly all teachers said social and emotional learning helps students manage emotional distress and reduces behavior problems, according to a survey by McGraw-Hill, a textbook company.

More than half of those teachers said their school began implementing a social and emotional learning plan. In general, those plans help students develop a healthy sense of self, manage emotions, reduce loneliness, gain empathy and maintain supportive relationships.

Education Secretary Miguel Cardona said the habits schools and teachers are developing to address mental health needs have staying power. The best habits require a fundamental shift in how the school day operates, he said.

"Does (the school day) look different?" Cardona asked in an interview with USA TODAY. Students, he said, need to know: "Are there activities that engage me with my peers, where I can talk and learn communication skills and express whether I'm feeling upset about something or be able to develop coping strategies?"

Less focus on testing

The pandemic meant a pause on required standardized tests, which are usually administered in person. Teachers have long complained that testing reduces actual learning time.

"We've been dangerously out of balance when it comes to our emphasis on test scores over and above physical health and mental health," Andrew Ho, a Harvard professor and director of the National Council on Measurement in Education, said in a Harvard education webinar in September.

Federal law requires states to administer yearly exams in key subjects in grades three through eight and once in high school, but states were given more flexibility this spring to administer those exams.

In Florida, officials proposed an assessment and accountability regime that would reduce the amount of time spent on testing. Gov. Ron DeSantis said the state will move toward using online, adaptive tests issued three times a year to measure student progress and hold schools accountable.

More tutoring and mentoring programs

High-dosage, personalized tutoring programs boost test scores in reading and math, especially for low-income students, according to a Danish study posted on the ResearchGate website. As a result, they've been touted as a way to help students make up pandemic-related academic losses. Students who lost the most ground are disproportionately children of color and low-income kids.

It'll take more time to measure the results of those programs once they're rolled out on a larger scale. Schools have sought outside help in the form of mentorship to help students progress academically, emotionally and professionally.

Green Dot Public Schools, a network serving 14,000 students in Los Angeles, Memphis, Tennessee, and Beaumont, Texas, matches students with mentors around the country. The commitment to match every student was made during the pandemic.

"The need to support our students in building social capital will exist long after the pandemic ends," said Theo Ossei-Anto, Green Dot's director of mentorship.

Richer out-of-school activities

During remote and hybrid schooling, millions of students spent less time in formal class each day. That exacerbated the experience gap between wealthy kids and not-so-wealthy kids, which contributes to achievement differences, according to research by Engage2learn, an educational services company.

As schools struggled to serve students' needs, community-based organizations, nonprofits and private groups filled the gaps. One technology company, Reconstruction, launched in September 2020 to offer an "unapologetically Black education" to students at home, through virtual lessons taught by experts vetted by the company.

Classes are $10 each, targeted to specific grade levels (plus adults) and focus on everything from cooking Black cuisine to reading Black authors to using applied mathematics to explore Black liberation, wealth and innovation.

"Families say they love the content, because their child isn't getting it in school. They love the tutor, and they love being in conversations with kids around the country," said Reconstruction CEO Kaya Henderson, former chancellor of District of Columbia Public Schools.

Many Black students don’t have options for out-of-school time activities that are culturally relevant, Henderson said. Hosting classes online allows children from different parts of the country to converse with each other, and it allows Reconstruction to hire professionals with expertise in specific subjects, no matter where they live.

"When kids see themselves represented in the curriculum," Henderson said, "they are more engaged."

Contact Erin Richards at (414) 207-3145 or erin.richards@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @emrichards.

Early childhood education coverage at USA TODAY is made possible in part by a grant from Save the Children. Save the Children does not provide editorial input.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Pandemic changes to school and education will be permanent