Palm Springs history: Modernism celebrated in new Architecture and Design Center exhibit

Modernism madness has just abated in town, but if still hungry for more, a trip to the Palm Springs Art Museum’s Architecture and Design Center to see its spectacular new exhibit “Albert Frey, Inventive Modernist” is in order, and will sate even the most voracious appetite.

Brad Dunning has curated an absolutely spectacular retrospective of the life and work of Frey, a now world-renowned architect, who chose to spend his life in the tiny desert town of Palm Springs instead of glamorous Europe or sophisticated New York.

Writing in 2014, Dunning noted, “Long before it was fashionable, Frey employed industrial materials in residential and commercial settings. He reached for longevity with his vocabulary of architectural materials.Frey aspired to maintenance-free buildings that didn’t need to be painted inside or out. He used concrete block, fiberglass, asbestos siding, and aluminum windows. He eschewed gypsum board and often clad his interiors in ceruse wood paneling. His buildings resisted earthquakes, rotting, and warping. His goal was timelessness both in materials and style, and he created a simple look that resists the winds of fickle fashion and is constructed in almost indestructible materials.”

Frey was basically creating, along with some other ingenious colleagues, what would come to be called “Desert Modernism,” and therefore the reason for the perennial fun and craziness that has descended on Palm Springs for a week or so each February for the past 19 years.

Such an exhibition is long overdue, and Dunning has masterfully put on display all the quintessential elements of Frey’s work, making his thoughts and processes intelligible and accessible.

Dunning has carefully traced Frey’s early development in Switzerland, work for the arguably the most famous architect in the world Le Corbusier in Paris, and then his move to New York. All documented lavishly in photographs, early architectural drawings, renderings, furniture and fine architectural models, these early periods are fascinating.

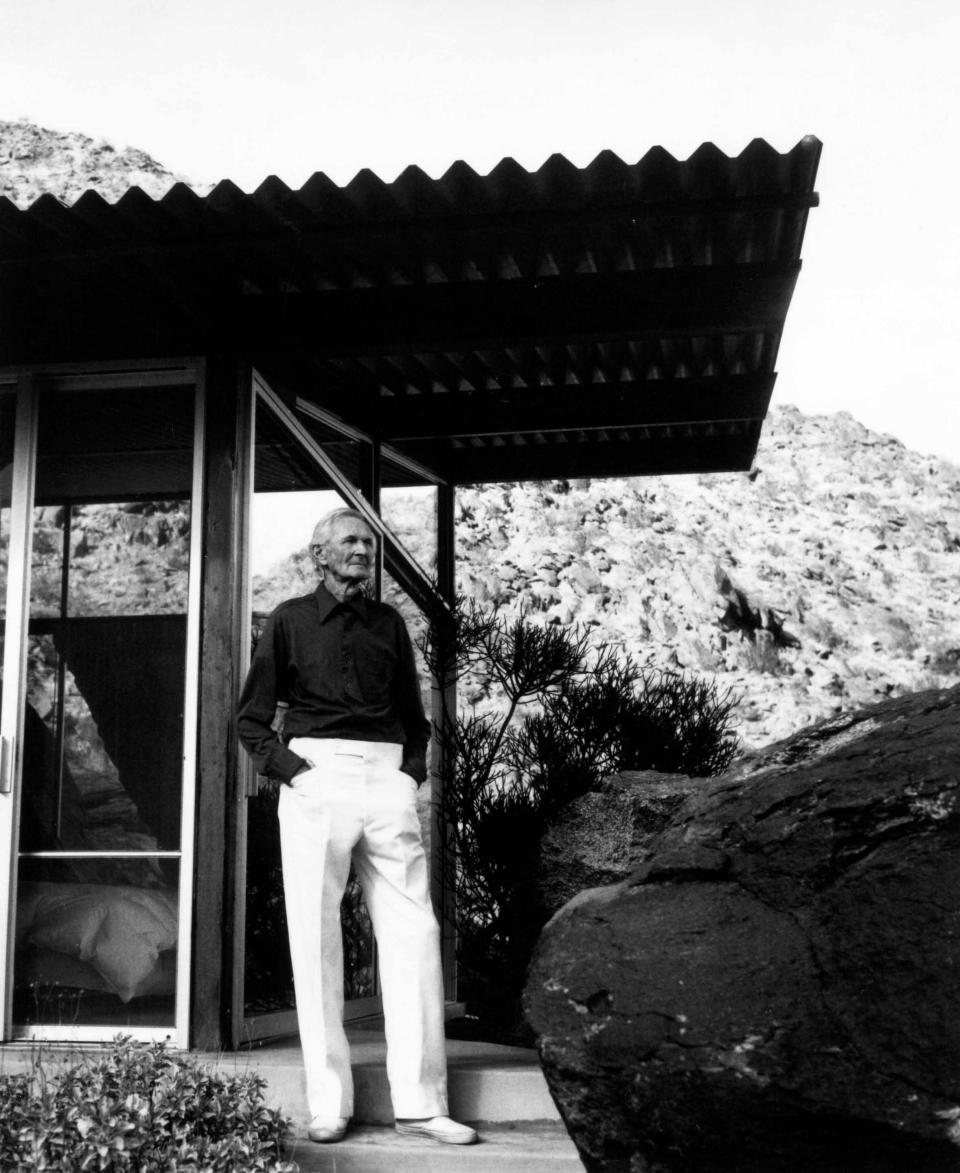

Remarkably, after all those places, Frey chose the desert as his home, and adapting to its particular conditions as his life’s work. He would likely have been much more famous in his lifetime had he accepted the prestigious jobs offered him in New York. But the desert captured him, and it proved more important than fame or money.

A prefabricated house designed with A. Lawrence Kocher called the Aluminaire was built and shown in the 1931 exhibition of the Allied Arts and Building Products Exhibition in New York. Constructed in less than 10 days of lightweight steel and aluminum, the Aluminaire would have cost only $3,200 if it had been mass produced in large quantities at that time. Using easily accessible building materials that would require little to no maintenance was a revolutionary idea.

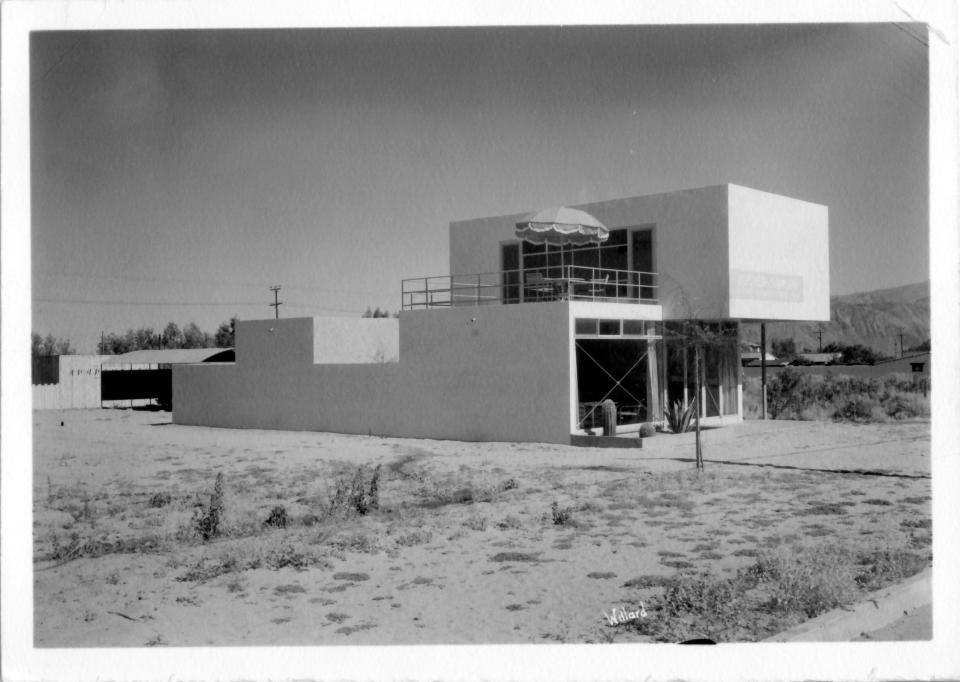

Frey arrived in Palm Springs in 1934 by sheer luck and happenstance. After working with Kocher on the Aluminaire, Frey was casting about for other jobs. Kocher suggested he go to the California desert to design a medical office building for his physician brother, J.J. Kocher.

Frey and Kocher designed a sleek, modernist, two-story “box” at 766 N. Palm Canyon Drive, with walls that could be slid into place to divide the space into various examining and waiting rooms and an interior atrium with a spiral staircase to bring in the outdoor light. The Kocher-Samson Building, as it is known, was the first modernist structure in the city, and is still stands.

Frey went back to New York to work on the Museum of Modern Art, contributing the now-iconic curtain wall of windows and the perforated rooftop patio cover. He had subsequent job offers to stay, but the faraway desert held more allure.

Returning to Palm Springs, Frey became immersed in the small community and began to work in earnest. For Frey, modern architecture represented a way of living, seamlessly adapted to its surroundings.

In partnership or collaboration with architects John Porter Clark, Robson Chambers and E. Stewart Williams, Frey completed dozens of residential, commercial and public commissions. He designed the Tramway Gas Station that greets visitors to town with its soaring roof. He was involved in the design of the Palm Springs City Hall, the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway Valley Station, the Bel Vista subdivision and dozens of houses, schools and commercial buildings. His own two homes would become iconic, with Frey II still extant.

Jeri Vogelsang writing in 2014 noted, “Frey’s typical desert buildings are low-lying, flat-roofed structures featuring horizontal bands of windows shaded by overhangs, and covered walkways and carports for essential shade. Guided by the belief that architecture should blend with and not dominate the natural surroundings, Frey attempted to satisfy the desert dweller’s aesthetic, physical and spiritual needs. His deceptively simple designs reconcile climatic, economic and environmental concerns.”

Frey looking back on a 60-year career in 1990 wrote, “In my youth, out of necessity, I had to produce a desired result with the least material and effort. Since then I found this principle to be a stimulating challenge to create, with aesthetic possibilities and gratifying the intellect. Today, realizing that resources are limited and with populations increasing drastically, conspicuous consumption is against the common good.”

Frey’s principles of good design provided a harmonious living experience within a community. He is responsible for pioneering an architecture adapted to harsh conditions with inventive design, now understood as its own distinct school of Desert Modernism.

Dunning illustrates the evolution of this architecture in glorious detail. The exhibition’s companion book belongs in every architect’s, architectural historian’s and architecture aficionado’s library and on everyone else’s coffee table. Fortunately, the exhibit is up until early June allowing for leisurely, un-crazed enjoyment of it. Palm Springs Art Museum’s Architecture and Design Center at 300 S. Palm Canyon Drive is open Friday through Monday 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

And as if finally following its architect to the desert, the Aluminaire House, Frey’s very first project in the United States, is now permanently home in Palm Springs as well. Resurrected after decades of being assembled and disassembled in temporary sites, it is proudly standing at the end of Tahquitz Canyon Way next to the museum and just down the road from Frey’s second home.

Tracy Conrad is president of the Palm Springs Historical Society. The Thanks for the Memories column appears Sundays in The Desert Sun. Write to her at pshstracy@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Palm Springs history: Modernism, Aluminaire House and Albert Frey