Oversensitive and overreactive: what is nervous system dysregulation and how can it be resolved?

Lately, everyone seems to be talking about what happens when the nervous system becomes “dysregulated” – including a cascading array of ailments both physical and psychological. Google searches for “nervous system dysregulation” have increased, and quick, easy tips for calming one’s nervous system circulate widely on social media; influencers claim to have healed physical and mental health conditions via nervous system regulation.

The concept of nervous system regulation may sound perplexing; not least of all because it’s often brought up in the same breath as myriad alternative, even faddish-seeming therapies, like hypnosis and cold plunges. Skeptics may wonder: what does the nervous system have to do with our painful emotional experiences? And can nervous system-related hacks help with our most stubborn, mysterious health problems?

What is the nervous system?

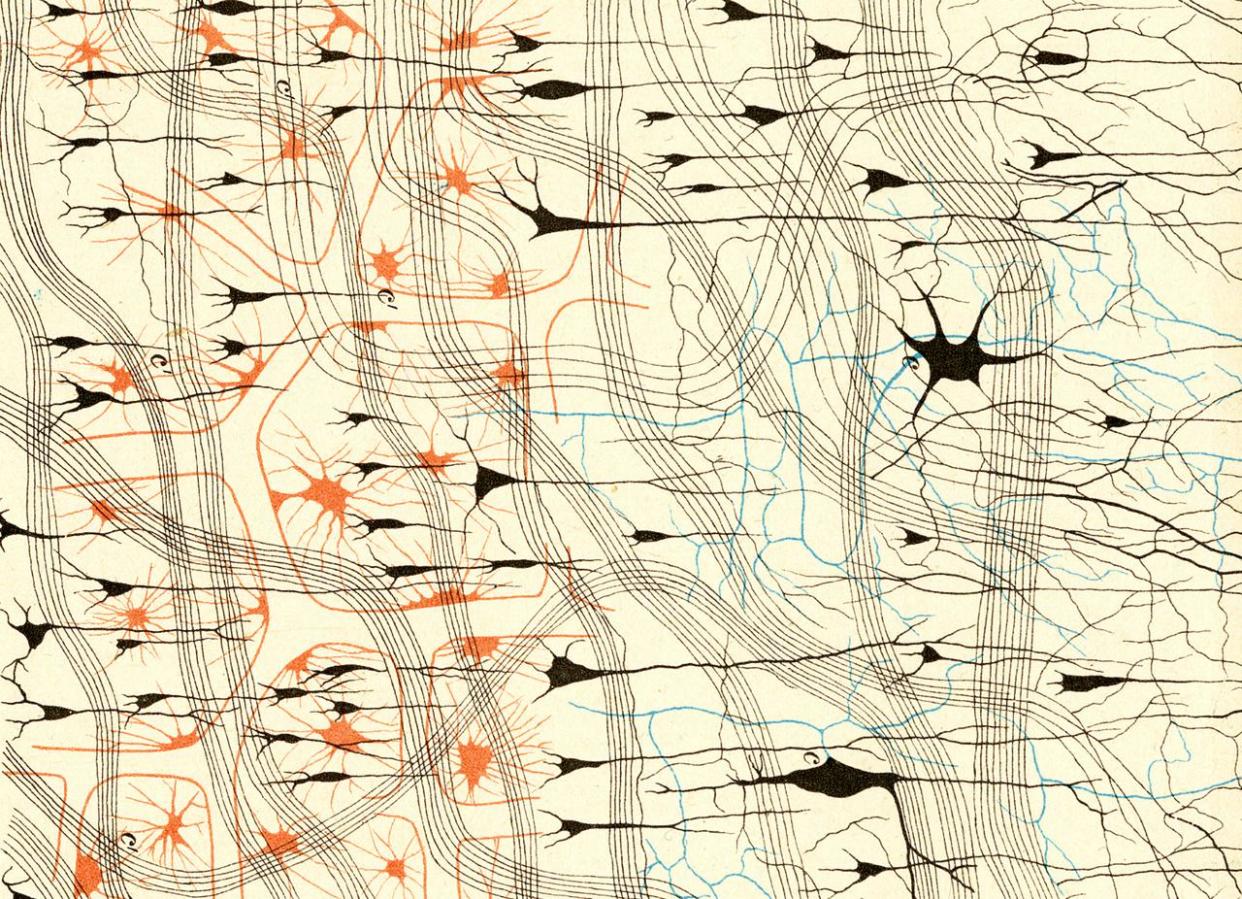

The nervous system is commonly described as the control center of the body, a network of nerves influencing many non-conscious physiological functions, including speech, mobility, organ processes and emotions.

Related: Can these 1,800-year-old-wellness tips help you live better?

It is intricate and not entirely understood even by experts. But a basic way to think about the nervous system is that it reacts to “any kind of environmental, social, psychological changes and structures that might impact us”, explains Dr Judy Ho, a neuropsychologist and Pepperdine University associate professor. It works in tandem with other systems, like the endocrine system, which regulates the release of hormones, to respond to events both mentally and physiologically, such as by making us sweat and tense up when threatened, says Ho.

The sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system are major subdivisions, responsible for sensations of danger and safety. The sympathetic nervous system gears us up for a “fight-or-flight” response to stressors, mobilizing the body’s resources to face potential threats. The parasympathetic nervous system is the body’s built-in mechanism for rest and relaxation, helping us recuperate and maintain a state of calm.

Currently, a core talking point about nervous system dysregulation is that it makes us oversensitive and overreactive to perceived threats, even if there is no rational danger – for example, when joining a meeting for work or setting a boundary with a roommate.

What is a dysregulated nervous system and how does it present?

“Nervous system dysregulation” signifies a state of imbalance between the sympathetic and parasympathetic systems. This can manifest physiologically – as it does in under 7% of the population – often as pain, fatigue, seizures, bladder and stomach issues, and partial paralysis. Medical professionals call these ailments “functional” or “somatoform” illnesses, meaning they are not linked to any perceivable disease and are instead attributed to the highly complex mechanisms of the nervous system.

According to Ho, dysregulation most often presents as emotional symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, a pervasive sense of depletion, irritability, overreactions like tantrums, underreactions like shutting down and difficulty shifting out of negative emotional states.

What causes nervous system dysregulation?

For decades, neuroscientists, psychologists and physicians including Bessel van der Kolk, Stephen Porges and Gabor Maté have theorized about the mind-body connection and ways that trauma and social experiences can affect nervous system regulation and thereby, mental and physical health.

Much of the contemporary, evolving conversation around nervous system dysregulation is based on a mix of theory, observation and research on the role the nervous system plays in social interactions, behavioral responses and memory formation.

Nervous system dysregulation can be exacerbated by immediate conflict, like an argument with your partner or the trauma of physical abuse. It can also stem from prolonged stress, such as an ongoing pandemic or a toxic work environment. Maté has linked it to childhood, when we develop personality styles in response to challenging emotional and relational circumstances, such as learning to take on other people’s problems in families where our parents overrelied on us for support, or suppressing our emotions to keep the peace in households full of explosive personalities.

Maté’s definition of trauma includes both “big ‘T’” and “little ‘t’ trauma”; the latter includes stressful but not cataclysmic experiences, that nonetheless prompt us to default to coping mechanisms, such as shutting down or desperately seeking approval, rooted in old fears of being physically or emotionally hurt. The theory of the mind-body connection posits that these difficulties can result in an imbalance manifesting as physical and psychological issues above and beyond what we may expect.

What should I do if I think my nervous system is dysregulated?

According to Dr Andrew Howard, a neuropsychiatrist and psychiatry professor at the University of British Columbia, people experiencing acute psychological or physical symptoms should see a non-mental health physician first to rule out disease. Then, the patient may benefit from talk therapy to identify the source of the body’s perceived threat.

Howard says it’s important to think about the mind and body as connected. Some people with stomach pain, for example, “can’t believe it’s their nervous system doing it”, says Howard. “But most physicians and psychologists can understand that connection.”

After these preliminary steps, however, there are few conventional paths.

“More often than not, we are encouraging people to see healers that are not physicians,” says Howard, who describes these issues as being “at the borderline of medicine”. If the issue is psychological or social, “physicians don’t always have an answer to the root cause of their problem”, he says.

A key part of addressing a dysregulated nervous system is to identify the source of unresolved stress. This source may be obvious to us, or, in keeping with Maté’s concept of “little ‘t’ trauma”, it may be linked to something we have been consciously or unconsciously dismissing as insignificant.

Related: What is lymphatic drainage massage and why do celebrities love it?

What are the treatments for a dysregulated nervous system?

Alternative therapies that practitioners commonly recommend for nervous system regulation tend to emphasize exploring the mind-body connection. For instance, “somatic experiencing”, developed by psychotherapist Dr Peter A Levine, focuses on helping people pay attention to the internal sensations of their bodies instead of the cognitive ones. This might involve tactics like noticing physical stress or tension and visualizing it dripping away from your body.

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, or EMDR, is a psychotherapy treatment some practitioners believe can alleviate the distress associated with traumatic memories. It involves a therapist using physical or auditory stimulation to help process negative memories and reduce their impact.

Diane Song, a California-based holistic coach pursuing a PhD in humanistic psychology, uses breathwork training to work with people who feel dysregulated. Song says she tries to foster autonomy in her clients: “Some clients will come to me and be like, ‘OK, I want you to tell me what to do.’” In response, she asks instead, “What does your body feel like doing?”

Bear in mind that in the wild west of alternative therapy treatments, practitioners may lack training or veer into their own highly subjective modalities that may or may not be safe or helpful. Talk to your doctor before attempting any alternative intervention, and be cautious of treatments that sound extreme or over-promise results.

Are DIY nervous system regulation tips useful?

Quick, easy tips for regulating your nervous system abound online. They often involve practices like yoga, taking deep breaths, cold showers or trying to stimulate the vagus nerve – which is located in the neck and associated with the parasympathetic nervous system – by singing, humming or gently tapping on areas of the body.

These are all harmless regulating practices anyone can do on their own. While they can be useful, some experts take issue with their hype. Jonathan Jarry, McGill University science communicator and podcast host, points out that tactics like breathwork and meditation work “through a very simple concept: relaxation”.

“Taking a moment to yourself to pause a stressful situation and focus on your breathing can, indeed, temporarily help with feeling unwell. The vagus nerve trappings are just scientific dressing, meant to transform common sense into a cutting-edge, all-natural body hack,” he writes.

Overall, regulating the nervous system is not only about helping us calm down in the moment, but also conditioning our bodies to react to stress more appropriately on an ongoing basis.

Once I regulate my nervous system, will everything be OK?

Holistic healing involves a sense of improvisation and discovery, and is not a “one pill fix”, says Song. When it comes to nervous system regulation and the idea of resolving trauma, there isn’t a widely applicable system that will work for everyone. Nor is it likely that life will be perfect if we just find the right somatic treatment or calming tactic for stressful situations, says Song. Rather, the aim of regulation is to develop a better understanding of how our bodies tell us they need care. “A lot of people say [regulation] comes from self-love,” says Song. “But I like to say ‘self-respect.’”