The original media moguls: how the D'Oyly Cartes transformed Victorian London

When I was growing up in the Sixties, the name of D’Oyly Carte generally provoked in my elders a patronising smirk. The eponymous opera company, still touring the provinces with traditional stagings of works of Gilbert and Sullivan, was on its last legs, perceived as a fusty Victorian relic for which the triumph of The Beatles and Carnaby Street was sounding a death knell.

Half a century later, however, G&S has proved surprisingly resilient, with updated productions such as Jonathan Miller’s of The Mikado and Mike Leigh’s masterly film Topsy-Turvy opening its joys up to new audiences – but the crucial role of the D’Oyly Carte dynasty and its creation and stewardship of the Savoy Theatre and hotel group has rather been written out of the story.

So a new book by Olivia Williams is to be welcomed as a reminder that “at their height”, the D’Oyly Cartes ranked as “the greatest impresarios and hoteliers in the world” – as dynamic, innovative and powerful in their way as any of today’s media dynasties.

Yet compared with the Murdochs or Maxwells, they were unbesmirched by scandal, innocent of ruthless corporate behaviour or internal strife. This was a matter of chance as much as anything else – two wild cards who might have proved disruptive died too young to have any impact, leaving the post-war years to be dominated by a dutiful and conservative woman without issue. Whether their solid unity and consistency of purpose was altogether to the good is another question.

Founder of the family fortunes was Richard D’Oyly Carte, born plain Richard Cart in Soho in 1844. As the genteel son of a vicar’s daughter and a flute player who turned his hand to instrument manufacture, he could have been a character created by Dickens. D’Oyly, the middle name by which he was commonly known, was his mother’s proud link to a defunct Norman barony. D’Oyly enjoyed a progressive education and won a place at University College London, but from an early age he was stage-struck and determined to make his name in showbusiness.

Having launched himself as an actors’ agent, he took out a lease on a rickety old theatre off the Strand called the Opéra Comique. Here Gilbert and Sullivan’s early collaborations such as HMS Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance were presented to huge popular acclaim that was duplicated on tour and in the USA. D’Oyly became sole producer and manager of the brand, on a three-way profit split, and big money was swiftly made. As Olivia Williams puts it, they made “an uneasy, combustible trio”, and shrewdly realistic D’Oyly had a hard job keeping both gouty, harrumphing Gilbert and lazy, hedonistic Sullivan in check. But behind D’Oyly was the bulwark of the remarkable Helen Lenoir, who began as his financially savvy backroom girl and eventually became his second wife.

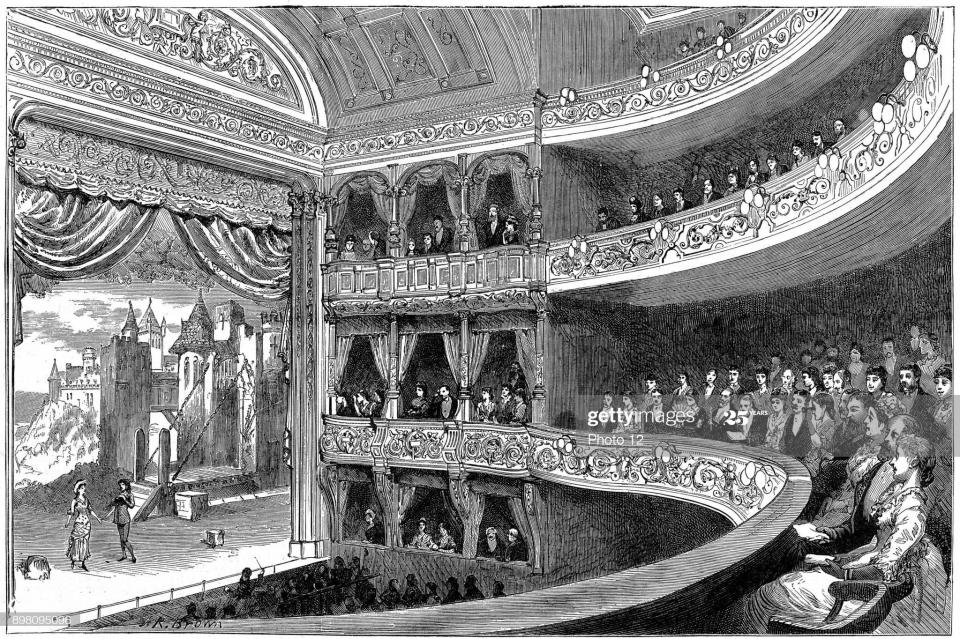

To showcase the partnership D’Oyly built the Savoy Theatre, which abutted the Thames Embankment and was one of Victorian London’s biggest regeneration projects and engineering miracles. This scheme made valuable real estate out of a dank marshy slum and became the hub of D’Oyly’s expanding empire. Devoid of a stinky gallery and rowdy pit, the Savoy Theatre, opened in 1881, was cleverly designed to appeal to the Pooterish suburban classes, and audiences flocked to a succession of beautifully staged G&S operettas in its plushly comfortable auditorium.

On the tide of international success for what came to be known as “the Savoy Operas”, D’Oyly embarked on the even more ambitious construction of the Savoy Hotel next door. If the theatre was aimed at middling types, the hotel was pitched at the luxury market, specifically the influx of visiting Americans. With its lifts, electric light, bathrooms, floor service and Frenchified restaurants, it was the last word in the glamour of modernity and remained the London hotel of choice for Hollywood stars and Greek shipping magnates for more than a century. Shortly before he died in 1901, D’Oyly went on to add the Palace Theatre, Simpson’s in the Strand and Claridge’s, as well as several foreign acquisitions, to his portfolio.

D’Oyly had two sons. Lucas, the elder, was potentially a disaster – thought to be the original of P G Wodehouse’s foppish twerp Psmith, he was dangerously mixed up with Oscar Wilde and a lover of Lord Alfred Douglas. But he died young from tuberculosis and succession passed to his sober brother Rupert, a meticulous and reserved man of impeccable respectability who handled his inheritance with aplomb and steered the Savoy Hotel elegantly into the age of jazz and cocktails.

Along with his stepmother Helen, Rupert kept the opera company under rigorous control. Given G&S’s unfailing popularity in the colonies and the USA, money continued to pour in until copyright expired in 1961, not least from recordings, but the insistence on preserving the letter of Gilbert’s stage directions meant that a spirit of tired routine began to infect performances.

Rupert had two children with his wife, the aristocratic Dorothy Gathorne-Hardy. Michael was the great hope – a clever and energetic Bright Young Thing whose passion for fast cars tragically proved fatal on a Swiss mountain road. His sister Bridget thus became the heir to the dynasty, a strait-laced, shy woman described by Williams as “a cross between Miss Marple and the Queen”.

Although helpless at one level (she smoked 80 cigarettes daily and “could not boil and egg or sew a button”), she proved a dogged defender of status quo and, with the help of her consigliere Hugh Wontner, resisted hostile bids for the Savoy group from the likes of Conrad Hilton and Charles Forte.

What she could not stop was the opera company’s decline. Denied support from the Arts Council on the grounds of its inertia, the company haemorrhaged resources, and in 1982 it expired. Various attempts at revival have been fruitless, but a charitable trust with capital of £60 million – 10 times bigger than the foundation established by today’s nearest equivalent to D’Oyly, Cameron Mackintosh – preserves the honour of the D’Oyly Carte name and distributes grants to musical causes.

The last of the line, Bridget died in 1985 – not surprisingly given her consumption of cigarettes, from lung cancer. One wonders ruefully what she would think of the Savoy’s current owner, Prince Alwaleed bin Talal, but she would surely be consoled by knowing that her grandfather’s babies, The Mikado, Iolanthe and The Pirates of Penzance, remain as much loved as ever.

Olivia Williams’s The Secret Life of the Savoy and the D’Oyly Carte Family is published by Headline at £20 on September 3