An Oprah Daily Exclusive, “Seen & Unseen” Chronicles Pivotal Moments in America's Racial History

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

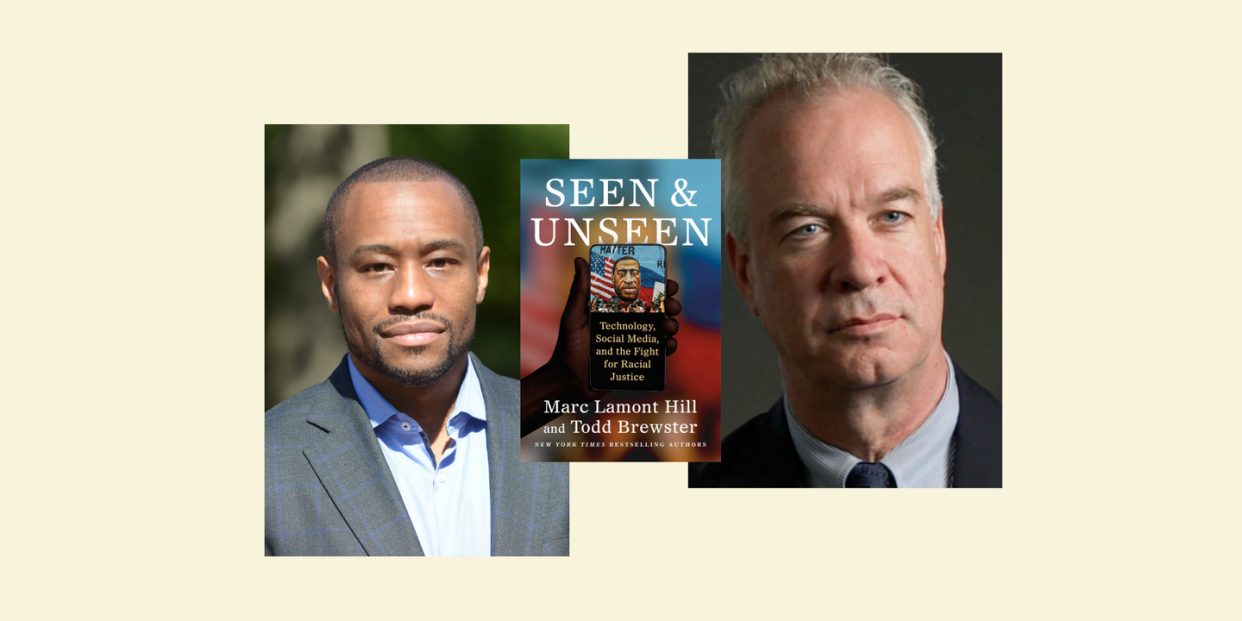

Zora Neale Hurston once said, “If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.” Decades later, on May 25, 2020, Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd on a Minneapolis street by forcing his knee on Floyd’s neck and cutting off circulation for just over nine minutes. What followed was a summer of protests from city to city around the nation and in many other parts of the world. Black people were silent no more, joined by those from other ethnicities and cultures. The question Marc Lamont Hill and Todd Brewster pose in their new book, Seen & Unseen (Atria Books, May 3, 2022) is, Why now?

Hill is the author of several other important works of nonfiction, including 2020’s We Still Here. He is also a political commentator who regularly appears on CNN, Fox News, and BET. A Philadelphia native, Hill is the Steve Charles Chair in Media, Cities, and Solutions at Temple University and owns Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee & Books in his hometown.

Brewster is a journalist and historian who worked as a senior producer at ABC News and was an editor at Time and Life. He coauthored three books with Peter Jennings and is the author of Lincoln’s Gamble and a founding director of West Point’s Center for Oral History. The Indiana native was inducted into the Indiana Journalism Hall of Fame in 2000.

From the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, pictorial and video evidence emerged of lynchings and protests. Those images were broadcast throughout the nation and across the globe, revealing both the racial violence and the social pushback against it that was happening in states like Alabama, Mississippi, and others. Hill and Brewster explore the later impact of smartphone recordings and social media in galvanizing protest movements. Silence is no longer an option. —Wadzanai Mhute

Chapter 1

It’s a simple question: why? Why, after so much writing and analysis on the prevalence of police violence directed at people of color—so much data, so many first-person accounts, and, finally, so much cell phone and surveillance video—did it take the video of the deadly violence used on George Floyd to trigger a broad response of sympathy and outrage about racial injustice? Why not the many instances that came before Floyd, why not the many, including the April 4 killing of Patrick Lyoya, a 24-year-old immigrant from the Congo, after a traffic stop in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and the mass shooting by an 18-year-old white supremacist at a grocery store in Buffalo, New York, that have happened this year?

The accounts of others who in recent years met the same or a similar fate as Floyd feels numerous, even if we recite only some of the names of those who became widely known—Breonna Taylor, Oscar Grant, Kathryn Johnston, Trayvon Martin, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner, Rekia Boyd, Alton Sterling, Mya Hall, Walter Scott, Renisha McBride, Michael Brown, Ahmaud Arbery, Rayshard Brooks, Philando Castile. All these victims shared one thing: our knowledge of them and their fates was enhanced through modern media tools that became available to us only recently—through cell phone and surveillance video, Twitter alerts and Facebook groups, and the sharing and replaying of footage, zoomed in to analyze every movement, zoomed out to determine context, dissected and repurposed, shown in courtrooms and on YouTube, and spliced to form memes.

It is clichéd to say that our age speaks through pictures, both real and imagined, more than ideas: a border wall; a rogue immigrant caravan; a roaming young Black man in a hoodie; a man with a knee in the neck of another man as he gasps, “I can’t breathe.” In the past, a photograph was an object, something to be held or framed or thumbtacked onto a bulletin board or published in a book. Think, for instance, of how our mind’s eye charts the story of the civil rights movement with images of Bull Connor’s Birmingham firehoses, John Lewis marching bravely across the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and 15-year-old Elizabeth Eckford walking fearlessly to Little Rock High School while being taunted by a crowd of white students.

But “pictures” of our time, millions of them, are regarded differently. Passed through our obligatory devices, they form something more like a persistent conversation, a parlor argument rendered through flash cards, one vivid image replaced by the next vivid image until the exchange drifts off like a text stream finally gone unanswered. That is, until, in a persistent rhythm, another exchange begins. Maybe a TikTok of men singing sea chanteys or customers brawling at a Walmart over the few remaining pieces of sale merchandise. There are so many “pictures” we can hardly keep up with them.

In the late 19th century, long before pictures became a prevalent form of discourse, Black journalist Ida B. Wells boldly published investigations of American lynchings. She did so because, otherwise, the dead “had no requiem, save the night wind, no memorial service to bemoan their sad and horrible fate.” Absent the effort of the chronicler, they were like the dead bodies of Union soldiers, left to decay in “an unknown and unhonored spot.” By exposing lynching for what it was—not the crazed violence of a fevered few but a festive ritual central to white Southerners’ conceptions of white superiority—Wells helped to initiate the modern movement for civil rights. But, finally, it was pictures of the lynchings, some of the same pictures that had been taken for sport by the white supremacists who reveled in the spectacle of death, that shamed the nation and put an end to the practice. And decades later it was a picture of 14-year-old Emmet Till’s mangled face that forced the nation to reckon with the brutal consequences of racism. The boy’s mother, Mamie Till Bradley, made sure of that when she demanded that his casket be left open for the funeral for “the world to see what they did to my baby.”

Those pictures had staying power. In our image-obsessed society, how is that Floyd and, sometimes it seems, Floyd alone, stood out in this cacophony, commanding not just our attention, but the world’s?

The answer to that question may well lie in the way that his death happened, the nature of the recording that showed it to the world, and the symbolic chords that it struck with American history. Like each of those other recorded incidents, Floyd’s comes with a story. In fact, a deceptively simple one. A man walks into a convenience store and passes a counterfeit bill. The store clerk calls the police, the officers confront the man, and he resists arrest. But, in fact, few people know those details. The “story” that is known the world over is the one that begins when officer Derek Chauvin applies his knee to Floyd’s neck and ends nine minutes and 29 seconds later when, still under the pressure of that knee, Floyd expires.

One reason for all that attention was that Floyd’s story resonated, deeply. It resonated with many whites because the cruelty inflicted on him was so undeniable, so elemental (“Momma! Momma! I’m through”), and so protracted that it could be neither ignored nor dismissed. A shooting is an instant; a lynching is a performance, and Floyd’s death was a modern-day lynching committed in a country with a history of lynching. His fate resonated with many Black Americans for the same reasons that it did for white Americans, but also because to Black Americans it was so familiar. Indeed, to them the power of the video was in its very ordinariness. They could see themselves in his suffering; or an uncle, or a sister, or even a long-departed ancestor. For George Floyd was, in a sense, the Black American “everyman.” And the video? It was nothing less than then a rendering of the whole sorry relationship between Black and white in America and, even more, the whole perverse relationship between the powerful and the powerless throughout the world.

Long before Minneapolis, the life story of George Floyd contained reminders of America’s long history with race: slavery, white rape, broken families, poverty, discrimination, caricature, drug abuse, prison. Born in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in 1973, Floyd was 2 when his parents separated, and he moved with his mother and four siblings to Houston’s Third Ward, a once thriving neighborhood that went into decay with white flight and the expansion of the highway system, allowing the white commuters in the new suburbs the opportunity to get into and out of the city with ease. Absent a monied class to attract investment, the social cohesion of the new urban Black neighborhoods was disrupted by the highways, and with that, the city’s old neighborhoods, including the Third Ward, went into a rapid decline.

Floyd grew up in Houston’s Cuney Homes, a public housing project made up of two-story brick-faced units (nicknamed “The Bricks”) that was built by the Houston Public Housing Authority back in the days of the New Deal. It was named for Norris Wright Cuney, a mixed-race politician who had been born into slavery, the product of his enslaved mother and the white master who had raped her. As a freedman, Cuney emerged during Reconstruction as a prominent voice in the Texas Republican Party; that is, until the “Lily-White Movement,” established to lure white voters back from the Democrats, ousted the “Black and Tans” from Republican ranks.

George Floyd graduated from the segregation-era Yates High School (formerly Yates Colored High School), which was named for yet another courageous post–Civil War Black leader, the Baptist minister and former slave Jack Yates. Yates was instrumental in the establishment of Emancipation Park, a patch of land in the Third Ward celebrating the end of slavery. But like so many achievements during Reconstruction, this one was spat upon when, in 1892, the road next to it was named for Dick Dowling, a Confederate general known as the “hero” of the Battle of Sabine Pass for successfully pushing back an attempt by the Union army to invade and annex part of Texas. In 1905, the city added a marble statue of Dowling, the first piece of public art in the history of Houston, in front of City Hall.

After high school, Floyd’s young life, like that of so many Black men, became animated by dreams of success in professional sports or rap music. But he failed at both and fell into a life that followed a sad yet common trajectory, one that moved to a rhythm of drugs, petty crime, prison, the church, and then drugs again.

Of course, the real challenge is whether the outrage that the video created will lead to a better future, and on that score, America’s track record, even when inspired by powerful visual media, is disappointing.

In May 1963, then Attorney General Robert Kennedy asked the writer James Baldwin to assemble a group of Black leaders to meet Kennedy and discuss the turbulent state of race relations in the country. It was shortly after the bombing at a Birmingham church that had taken the lives of three young girls, an attack carried out by the Ku Klux Klan and with the cooperation of the Birmingham police. The streets of Birmingham had erupted in violence afterwards, and, in scenes well documented by photojournalists, the police had used brutal tactics to suppress the protesters. The photos had humbled the nation. Kennedy aimed to steer the administration of his older brother in response.

Among those whom Baldwin chose for the get together was the playwright Lorraine Hansberry, whose most famous work is A Raisin in the Sun. The meeting did not go well. Kennedy appeared more interested in getting beyond Birmingham than in facing its awful truths. According to Baldwin himself, Hansberry’s departure from the meeting was exceptionally chilling. After expressing her disappointment in Kennedy, she made reference to the images coming out of Alabama when she professed to be “very worried about the state of the civilization which produced that photograph of the white cop standing on that Negro woman’s neck in Birmingham.” Then, she smiled, before saying goodbye, Baldwin remembered, and he was “glad that she was not smiling at me.”

Nearly 60 years later, it was a different kind of “photograph” that caused concern about the “state of the civilization.” But the message was the same: get your knee off of our neck.

Excerpted from Seen Unseen: Technology, Social Media, and the Fight for Racial Justice, by Marc Lamont Hill and Todd Brewster. Copyright © 2022. Available from Atria Books, an imprint of Simon and Schuster.

You Might Also Like