The Only Son of a Ladies Man

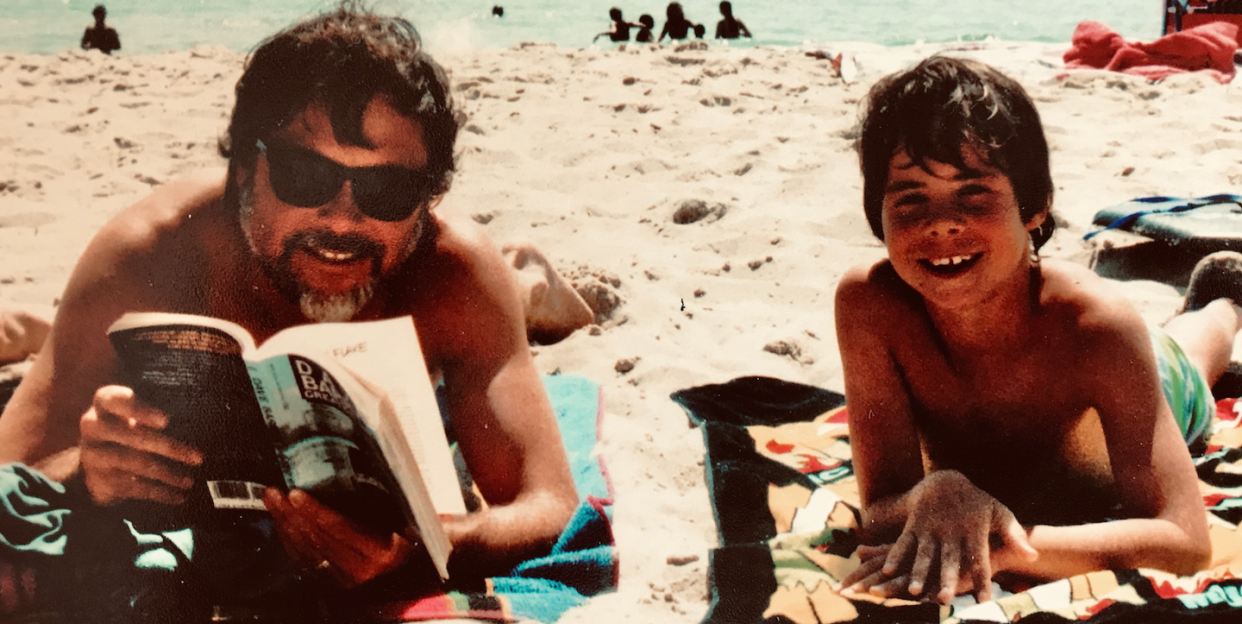

It wasn’t until a decade after his death that I learned my father was a womanizer. I was sitting on a beach in Florida with my mother. She stared out at the waves and said, “Your father cheated on me. That’s why we got divorced.”

This discovery of one family secret led to another: My father spent years conning my wealthy, former stepmother (picture Dirty John, without the violence). And another: my father had girlfriends, mistresses who he’d visit with when he was traveling on business. He’d even had the stones to drag me to lunch with Susan, his girlfriend of the moment, when I was four. (I promptly returned home and began raving about her to my mother: Susan is funny! That was probably the day Dad stopped trusting me.)

Robert Bly, an expert on the male psyche, and author of 1990 bestseller Iron John, used to say in many of his lectures that psychic “food” is passed from the father’s body into the son’s as they spend time together. This cellular level transfer is made up of mannerisms, beliefs, and behaviors the son inherits—essentially a program on how to be a man in the world. And since I watched my dad chase girls, I became a ladies man, too: a tailored suit wearing, champagne swilling fashion journalist in New York City. But behind the cool clothes, behind the reputation as a suave heartbreaker, I held onto a well-guarded secret: I was terrified of women.

All men grow up a little afraid of women. That’s how it works in a culture where the majority of our fathers aren’t present emotionally, or present at all. We cling to women for comfort and safety. Sam Keen, author of Fire in the Belly: On Being a Man, writes that since the industrial revolution, a son is more likely to have remained a “mama’s boy” than to have identified with any powerful, male authority.

The fact that we’re a culture of men dependent on women isn’t inherently a problem, though. The problem is that we deny it. “Most men spend their life defending against, and reacting to this unconscious bondage to women,” writes Keen. “We say things like: Real men don’t depend on women. We stand tall and alone.” But any straight guy knows this is bullshit. The endless, anxious struggle most of us are engaged in to find the “right” partner is proof of our denial. So are the typical stalemate dynamics and high divorce rates of male-female marriages in this country and others. And when we deny something so vehemently it gets pushed deep into the unconscious, into what Carl Jung called our shadow.

We’re seeing the disastrous effects of the shadow masculine right now. Gender relations seem, on the whole, stalled. Men are harming women and have been for a long time—that we know. But it isn’t because masculinity is inherently toxic. In fact, what I’ve discovered working with hundreds of men as a therapist and life coach is that guys desperately seek connection, love, and conviviality with their female partners, lovers, and friends. They just have a lot of conditioning to unwind. Conditioning that starts, like mine did, at a young age.

With my dad off working and gallivanting, I spent most of my childhood around the women in my family. There was my mother (sweet and sad), my stepmother (cool and critical), and my grandmother (a real charmer before the scotch came out). With all three of them, I felt inadequate. As much as I read the room, as much as I shifted my behavior to accommodate their moods, I could never seem to cheer my mom up, or measure up to my stepmother’s lofty standards. My grandmother buried the deepest dagger when she told me, drunk at a family Thanksgiving, “You’re a terrible son.”

Convinced I’d failed as a son, and as a man, I hid a lot in my room. It was there I discovered another kind of woman: models in magazines, actresses on television, porn stars on the internet. These experiences only exacerbated my limited, and archetypal, understanding of women: they were either Madonnas or whores, goddesses or bitches. They had both the power to save me, or destroy me. Either way, they seemed insurmountable.

When I was 22, something happened that made me fear women more than ever. My father died by suicide. The previous year, I had watched him spiral out after his latest divorce, transforming from a titan into a person I didn’t recognize: a weak, vulnerable man crumbling without a woman by his side. Then, one morning, he was gone. After his death, the project to turn myself into a ladies man happened unconsciously. All of us want to be attractive, but my dad’s death made me believe on some level that my life depended on it. If I couldn’t get and keep a woman, I’d end up like him.

Luckily, a few things happened in my mid-twenties that shifted my woeful fortunes with women. First, I got sober and lost twenty pounds of post-college beer weight. Then I moved to the East Village, bought a leather jacket, and grew a beard, like my dad’s, that made me look just a little bit dangerous. Miraculously, I started attracting women. Lots of them. And by the time I was scoring gigs writing for magazines like Esquire—which gave me instant access to parties, photo shoots and runway shows full of some of the most beautiful women in the world—I was like a drunk let loose in a distillery. I slept with as many women as I could in those years: downtown hipsters, models, Olympic medalists. Give someone a little power and you’ll see who they truly are, right? I was a cad. Just like my old man.

One summer, I met and fell in love with Amy. She was the epitome of the women I chased during my ladies man years: tall, freckled and Celine skinny. And with her by my side my ego surged. We spent a blissful year together tearing around the city, or shacking up in my studio, having sex, and ordering Seamless. But then she started to move on, and I panicked. It was like a sensor in my body that went off: SOS. The woman is leaving. You’ve seen this before. You know how this ends. Suicidal and desperate—just like my dad had been a decade before—I did the only thing I could think of: I called my mother.

Mom had entered recovery for her own codependency and love addiction in her mid-30s, and spent three decades as a social worker. I went to visit her in Florida, told her about how I was suffering and desperate over Amy, and she put a book in my hands: The Flying Boy: Healing the Wounded Man, by a Texas therapist named John Lee.

“This helped me after your father left,” she said.

Lee’s story of recovering from an epic breakup floored me. I’d never heard another guy admit to feeling powerless over women before. Full stop. And it took me about three seconds to realize I felt the same way. All my life I’d been told my dignity as a man depended on my ability to dominate women, but in reality, they controlled me.

I knew my womanizing had been an attempt to regain a sense of power when I felt none at all, and when my mother told me about my father’s philandering that day on the beach, something clicked. I started to see that my mysterious father and I shared an Achilles heel. And that any study of my own relationship with women surely included the man I’d been trying to forget for close to a decade. So I hopped in the car and drove to my hometown in Maine determined to unearth the truth.

The process of learning our father’s secrets is a key piece in any man’s journey. But for most, it’s not an easy process. Our father may be distant, distracted, or unwilling to speak. He may be shy, drunk, defensive, or dead. Maybe we never knew him at all. My old colleague Michael Hainey’s memoir, After Visiting Friends, proved to me in the earliest days of my search that hunting down my dead father’s secrets could be possible. I’d just have to summon every scrap of journalistic chutzpah I had.

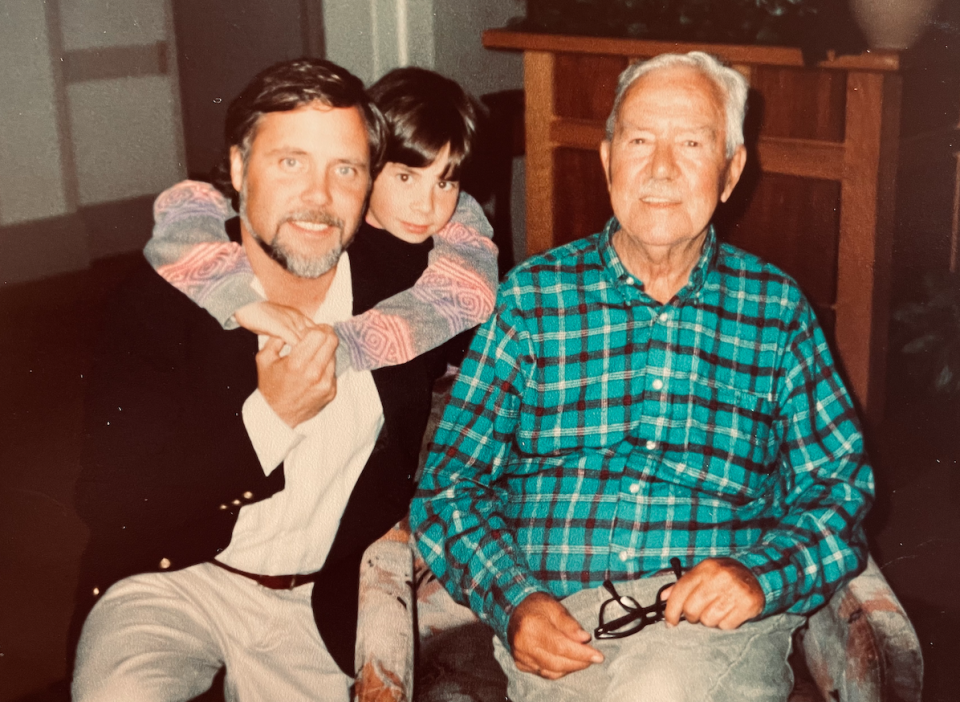

During the summer of 2016, my Brooklyn apartment became my war room: the walls plastered in Post-It notes, the floors covered in boxes of old photos and letters of my dad’s. I wore his watch, I listened to his records, I made phone calls or visits to everyone who’d ever known him: colleagues, roommates, doctors, trusted friends, wives and former lovers.

As I did, a picture of a man and his relationships came together: Like me, my dad had grown up with an absent father—a charismatic alcoholic. Like me, he had found solace in his mother, and learned to see himself through the eyes of women, to make himself attractive to them, to use their desire and approval as a way of feeling okay about himself.

Discovering these parallels was initially a chilling experience. A Mac Demarco song I was listening to at the time put it perfectly: Uh oh, looks like I’m seeing more of my old man in me. But as the process went on, I came to see our shared experience as a gift. It was as if my father had laid out a roadmap with many of man’s potential pitfalls double circled in red ink. By studying his mistakes, perhaps I could avoid them in my own life.

I knew dismantling my suave, "ladies man" exterior was the beginning—a process that started in men’s groups, where it was safe to talk openly about my fears and inadequacies as a man, and my struggles with women. When I did, I was shocked to find out other guys tussled with the same fear, anger, and imposter syndromes that I did. This discovery led me to start a life coaching practice for men: I wanted to give the gift to other men that my father’s wayward life had given to me. As I began to see myself and my worth through the eyes of other men, my self confidence shifted. I started to feel more confident, more whole.

Coming clean with the women in my life was much scarier, though. I felt so angry, hurt, and betrayed by both my mother and stepmother, and sharing this with them was nothing less than harrowing. I thought they might never speak to me again. Instead, they offered me friendship, support, and the space I needed to process.

As a part of my twelve step programs, I also reached out to many of the women I’d dated and slept with to make amends. These were some of the hardest conversations. To hear the pain I’d caused these women was difficult, but, with time, I forgave myself, knowing that I was acting from pain. In fact, if there’s one thing I learned through my many Come to Jesuses with women, it’s that every human being brings their deepest fears to an intimate relationship. And the real heroics come not through denying those fears, but by being willing to accept them, and work through them together.

Amy was the hardest to let go of—it took years, and even required a visit to John Lee’s living room in Texas to get me to go through with it. (“We have to face the things we’re most afraid of,” he told me.) When we finally said Goodbye, it unearthed some of the deepest grief. I spent many days and nights crying for Amy and for all the other women whose desire and approval had soothed my oldest pains around my dad’s absence and my own feelings of never being good enough.

As I healed, the great affairs disappeared. Some days, the reprieve from my never-ending chase for romance feels like freedom. On others, loneliness surfaces, and I wonder if I’ll ever find the partnership I know is out there for me. In the meantime, I’m learning—for the first time—to experience healthy bonds with women: relationships built on trust, intimacy, and mutual respect, not on old fears or power dynamics. I’m learning to be myself, which is the scariest thing of all.

I miss my dad a lot, especially this time of year. I miss his laugh. And his hugs. And the way we’d watch the U.S. Open together on Father’s Day Sundays. For a long time, the belief I would succumb to his fate haunted me. And it’s taken me nearly as long to understand that isn’t going to be the case. I am safe. I am strong. I am my own man. Surrounded by my family, my clients, and friends who love me for who I am—not a persona I created—I realize for the first time something that my dad never could: We are never alone.

You Might Also Like