After One Writer Finds Out She Has a Brain Tumor, She Confronts It Head On

“We have to talk,” the doctor in my local Brooklyn E.R. says, pulling up a chair up next to my bed. He’s holding CAT scans, presumably mine, slightly fanned like a messy hand of cards. I know as well as anyone that the phrase he’s just uttered is never followed by good news, but my thoughts skip around looking for options while my mouth says, “OK.”

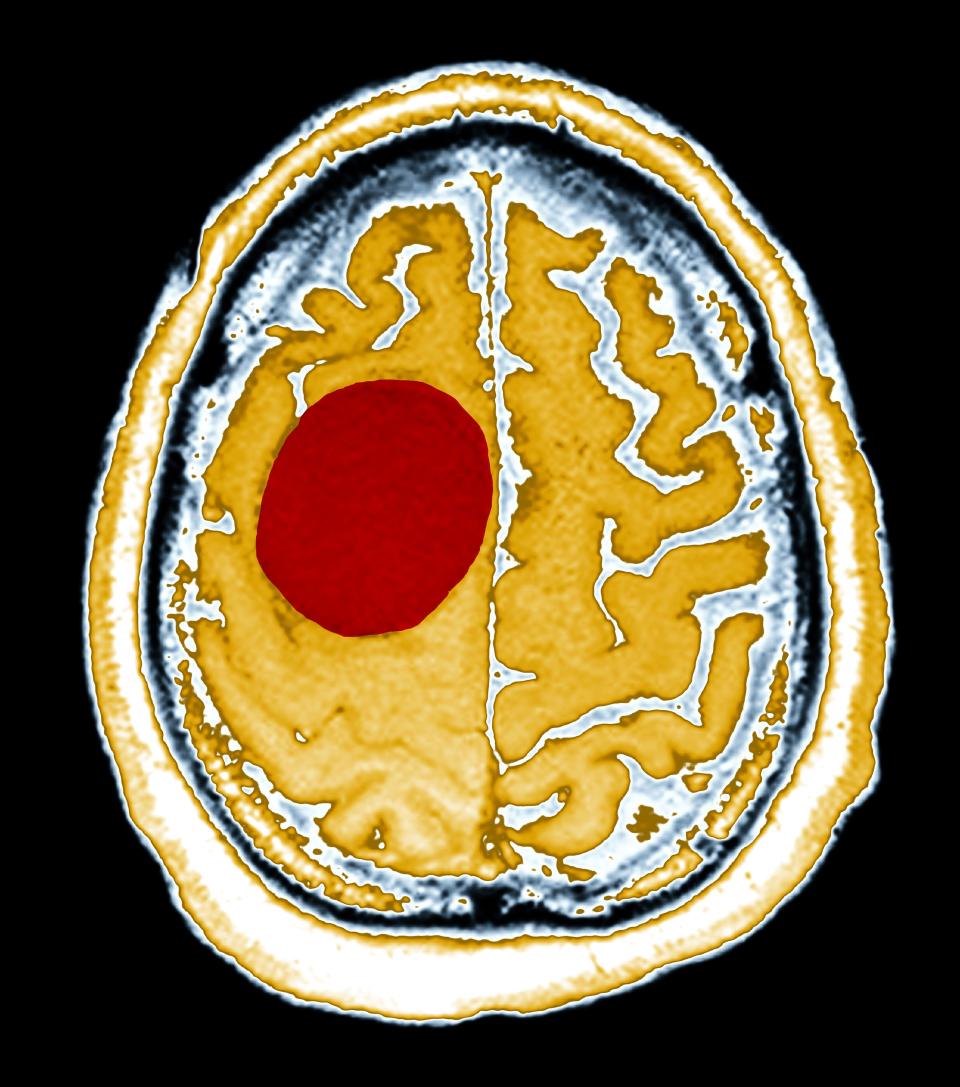

“There is a large mass growing in your brain,” he says. His expression is pained as he points to a sizable black blob at the upper right of one scan. “I’m 80 percent sure it’s something called a meningioma, which occurs in the outer layer of the brain, the meninges, and is benign. If it is that, it’s the best kind of brain tumor to have.” You really just said that? I think. “But it’s gotten so large it’s making your brain swell, which is why you have this headache.” The one I’ve had for a few days that woke me up sobbing at 3:00 a.m.

“I want to schedule an MRI to see it more clearly, and we’re going to add steroids to your drip, which should help with the pain.” This last part is very exciting because the morphine has only rounded out the sharpest edges of it.

“That sounds good,” I almost chirp. I have no points of reference for this. Can a mask of pleasant practicality offset the roiling inside?

My good friend Marie-Helene, who brought me here early this morning, offers to go get us iced coffees while I call my closest confidante, who is on vacation in Maine. When I hear her voice I collapse, mewling, “Kaaaatie.” “OK, OK,” she says firmly, gently, but when she hears meningioma she reminds me that her friend Chelsea had one in her 20s that she fully recovered from. She also says she’ll fly down for the surgery. I want to say, “Don’t trouble yourself,” but I can’t.

Handing me a paper bag with my coffee, Marie-Helene says, “I got you a cardamom bun. I figured since you won’t be going to India.” I hadn’t registered that fact. Two weeks from today, I have tickets to fly with my two children to Cochin, where I will introduce them to a place I have loved my entire adult life.

The trip was important for many reasons, but at its heart because it meant I was free from the separation and divorce that had wrapped its tentacles around me for five years. Love and commitment didn’t unravel so much as detonate. Then, after we filed our divorce agreement eight months earlier, I got two dream magazine assignments, one in India and the other in Uzbekistan. Suddenly absence and loss were replaced by freedom and possibility. Returning to India meant I was fine—even possibly wiser and stronger for what had come down the pike. Except now there is this.

After the MRI, the consulting neurosurgeon tells me that he is 98 percent sure the giant mass is a meningioma. Though slow-growing and benign, it must come out soon. Benign is not the same as benevolent. I’ll have to stay overnight and get a second CAT scan to make sure there are no “matching tumors” in my ovaries. I’ll skip those, I think.

The next morning, with my mom at my side, I am set to go meet a neurosurgeon in Manhattan who’s come highly recommended. On the phone he introduced himself simply by his first and last name, no “Dr.” preceding it, which I liked immediately for its assumption of an equal footing between us. In his waiting area, Chelsea—of the onetime meningioma—stands tall, smiling, with her bike helmet in hand. See? She’s fine. “Hi, head case,” she says, giving me a hug. She’s offered to take notes, which is good because my mom and I are frayed.

A computer screen in the surgeon’s office shows an MRI of my head with a vivid gray mass in it. My son will later liken it to the peach emoji, though Marie-Helene and I have dubbed it the “toxic mango,” as we try to make sense of its size and the fact that it has replaced my trip to India.

The awaited surgeon bounds in. With an easy smile and strong handshake, he is someone I might have known in college. He asks me about myself, my family, my symptoms. I’ve been relatively well, I say, traveling for work to India and Uzbekistan——

“Uzbekistan?! What were you doing there?”

“I was reporting an article and doing a surprising amount of dancing,” I say, happy not to be discussing the hijacker in my head. He laughs. I tell him it was hard for me to handwrite notes there—I thought it was the heat—that I’ve been unsteady going down subway stairs for a year or so and generally exhausted, which I assumed was a by-product of my divorce. He nods sympathetically.

He says the tumor is remarkably big—9 x 8 x 7 cm. This feature rather than its placement is what makes it a danger. The skull is a finite space. In a relatively good region—the posterior right parietal lobe, or “the silent brain,” as my surgeon calls it—it crosses over the top into the left hemisphere and may have affected my tactile and visual sense, as well as my understanding of space. Because the tumor has been growing for decades, the brain has mostly been able to adapt.

“Will we ever know how old it is?” I ask.

He looks at me thoughtfully. “Somewhere under the age of 47.” I think of the headaches I’ve had since I was twelve and the awful ones during both pregnancies (hormones are thought to feed meningiomas, which are twice as common in women as men and can often be misdiagnosed). To explain them, I decided I was someone overly prone to stress, but what if the headaches were not from a maladapted coping mechanism but the cause of it? Though far from the frontal lobe (language, memory, cognition, emotion), the tumor had stealthily taken over a third of my brain’s rightful space. How had it changed me over the decades?

Surgery will happen in six days, with steroids to manage the brain swelling in the interim. The surgeon—now my surgeon—asks me to bring in my children before then so he can reassure them “that their mother has another 52 good years ahead of her.” I am touched that he has thought of them and that he thinks I’ll live to see 100.

When I walk into my ex’s house, my thirteen-year-old son says, “Look what I got for India!”—a hard case for his camera. I tell him why we can’t go, in the mildest possible terms. “I can’t believe it,” he says, eyes tearing up, and hugs me. My ten-year-old daughter is outside playing with a friend. I call her in and blurt the news because I know it will be awful.

“You’re joking!” she says.

“No, I’m so sorry.” She bursts into tears and runs out of the house to the back. I follow her, but it’s clear it has to be processed in a stormy way. My ex is genuinely concerned, and I am polite.

That weekend, nausea is my near-constant companion, and ginger its only foil, candied, in cookies and gum all day long. We barbecue with my brother’s family, but I am in a state of disbelief. What else don’t I know about myself?

Monday morning, my son skips camp and my daughter throws up before attaching a rainbow unicorn horn to her head to go meet my surgeon. (She will wear it constantly for the next week; he asks her whether she might need surgery to remove it.) The children sit collapsed against me while my son asks about the size and nature of the tumor. My daughter asks who will cast my internet vote the day of the surgery for the landscaping competition Marie-Helene’s company is in. For one child, head-on questions and worry; for the other, magical thinking and aversion. I can relate to both.

As we leave, my surgeon pats me on the shoulder, as if he alone notices that I have completely wilted. A stranger four days ago, he is now at the center of my existence.

When we get home I crawl into bed, upset, and call my ex. Not my usual inclination, but I tell him our kids need him. He says of course he’ll take them before surgery, keep them, and bring them to see me. This is the first time he has made me feel better about anything in about a decade. Then he says, “I can only imagine how weird this week has been for you. It’s been weird for me. I thought, I don’t want to raise these children alone.” Filter, dude! You need a filter, my onetime love. I understand that he thought it, and I know his speaking it comes from a sense of residual closeness. We’ve always been honest with each other, and we shared so much. And yet he could have waited.

When Katie arrives the day before surgery, we lie on my bed and talk about my fear of dying. On the surface unfazed, she says it’s part of the process. We know the odds are very good: only a 1 to 2 percent chance of things going wrong—stroke, seizure, hemorrhage, problems with anesthesia. However, the tumor, in crossing the brain’s midline, abuts and has possibly invaded a major blood supply. Even if that’s not an issue, the thought of having my head cut open and the site of my very self exposed to the open air and other people is unnerving.

That evening in the garden, among the purple blooms of the butterfly bushes with my family and my closest friend, I am content. If this is the last night, it is a good one. Just before bed, I catch myself in the mirror and am surprised to find myself beautiful. This doesn’t look like a body that’s about to die, I think. But death doesn’t care a whit, does it?

In pre-op, I hold my surgeon’s hand too tightly. “What I want to tell you is,” I say, fresh from my insomniac hours, “I have people to love, children to raise, books to write, and I really want to swim the Croatian islands next summer.” How many versions has he heard of this plea? More subdued than before, he tells me everything will be all right.

I turn to Katie and Marie-Helene: “First of all, if I die give all my organs, everything away.” Dead but useful; good. “Also, whatever you do, don’t scatter my ashes in Marfa”—the West Texas town I have been a part of for 20 years that has become disconcertingly hip—“and please stay in my children’s lives.” I don’t want my ex raising them alone either. “Katie, if you can do something with my writing, OK. If not, that’s fine, too.” So fast and breathlessly, my whole life encapsulated.

As the anesthesiologist guides my bed away, he says, “You know where I wanted to go this summer? Split. Apparently it’s so beautiful that you stop for a morning coffee and stay three hours looking at the sea.”

Eight hours later, I hear the voices of my parents and two friends saying, “Hello, Daphne?”

I’m lying flat, my head aches, but I am so excited to be alive. Asked who the president is, I answer, “Trump, and I don’t want to talk about it,” satisfied that I know this much. But even with morphine, it feels like screws are being tightened at the base of my skull. When my surgeon arrives, he folds the bandage over, an easy fix. The tumor was completely removed, he tells me. I am free.

My parents are quieter than my giddy friends, and when my children arrive they are scared. I kiss each of their hands. “Don’t cry. I’m fine. I promise,” I say, and Marie-Helene delivers them back to their father.

An MRI in the morning shows the open space where the yellow-tan mass was. The squashed part of my brain might unfurl partially or fully. It depends on how long and how hard it’s been compacted. Neuroplasticity is now a word I find beautiful. When the surgical dressing comes off, my hair is still a fluffy, wavy bob, with just a long, thin C-shaped track marking the hatch. I can feel it but can’t bear to touch it. My friends and I joke about how if only there were hinges I could store things of value inside, maybe become a drug mule. When my children visit, they crawl into bed with me and eat cupcakes.

My parents whisk the children away to Milwaukee while I recover, and my close friends gather round. During the days, visitors drop by my sunny kitchen, bringing flowers, food, and news of the outside world. I drink in their company as ravenously as I eat their treats. Everything seems charmed, even in my utter weakness. Then, each afternoon, I sleep as deeply as an infant does. The synapses must realign. Spread out, brain. Spread.

If the days are celebratory, the nights are when I do my reckoning. At two or three, I wake up alert and alone. Before the operation, I avoided the internet. Now I can’t turn away. I read a Times article about meningiomas, straightforward until the Comments section, where angry readers write that they have never fully recovered. People contend with seizures, numbness, cognitive issues, migraines, dizziness, regrowth, and more surgery. Shaken, I quit out. I listen to a memoir by a British neurosurgeon called Do No Harm. I am riveted until I can’t bear it.

Six months later, after what seems like a longer recovery than I had anticipated, I am feeling mostly well again. The left side of my body does occasionally seem to go off-line—so that I have to instruct my left foot to now take a step after my right one. At the same time, someone who I know to be three feet from me seems to be at the end of a long corridor. Initially unsettling, these intermittent symptoms gradually fade away.

Clearly, the line between lucky and unlucky is very, very thin: the fact that at the outset I was still in New York; that I presented with a headache, not a grand mal seizure; that my tumor was a meningioma, not a glioblastoma, the kind that Beau Biden died of in 2015, born the same year I was. The events seem arbitrary, and yet I can’t help looking for meaning. I wait for some cosmic compensation. A minor superpower, please. But of course, the reward is ordinary life, and there is so much left to figure out—the stories I want to tell, the person I want to be, and in the meantime, what to make the kids for dinner.