One Writer Discovered By Accident That Her Family Perished in the Holocaust—And Set Off on a Quest to Learn the Truth

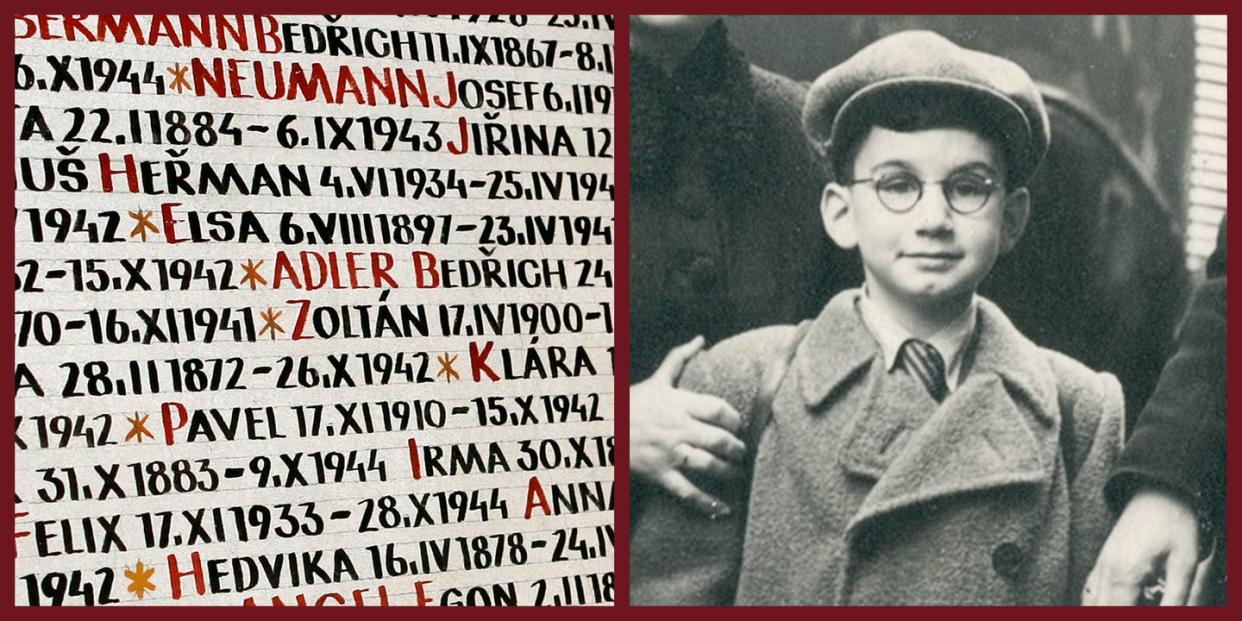

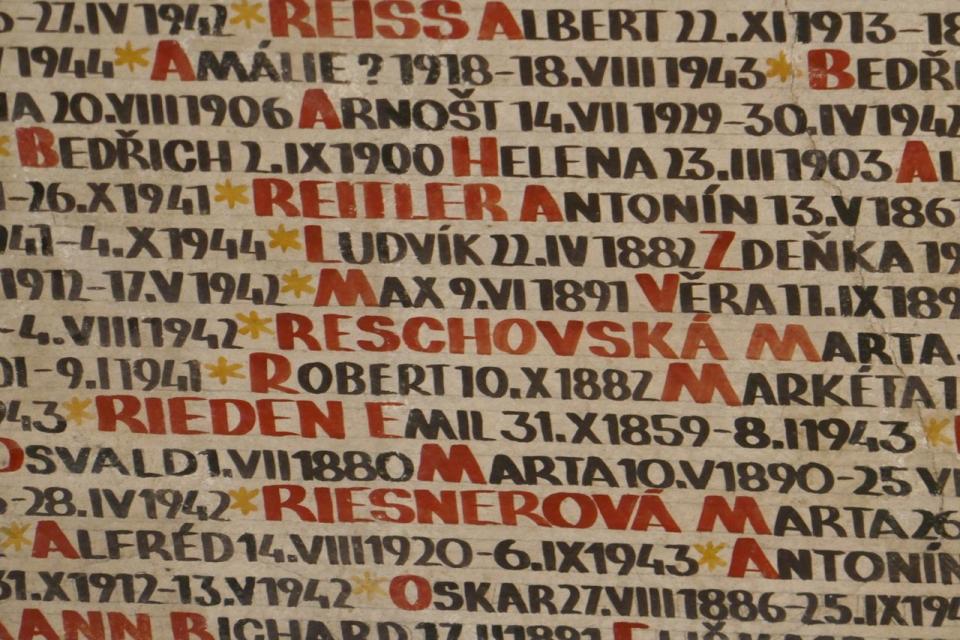

As I stare at the wall of Prague’s Pinkas Synagogue, I feel a blaze of heat flush through my body and my heart begins to pound and stutter. The etched letters are dancing in front of my eyes, the red now taking on the ghoulish taint of dried blood. My knees buckle and I grasp the railing in front of me, gripping it white-knuckle tight. An uncomfortable tingling is running up and down my spine. Retreating, I turn away and bend secretively over my phone for a frantic internet search.

And then everything changes.

It makes me sad and a little angry that I discovered the family I never knew from Google. I held my breath as I jabbed in the names I had just discovered on the wall—Emil Rieden, Berta Rieden, Felix Rieden, Ota Rieden—and then added "Holocaust" to my internet search. Could these really be my people on the wall of this memorial to Czechs murdered by the Nazis?

The answers came at one click. It was that easy.

Emil was my great-grandfather, Berta and Felix my great-aunt and great-uncle, and Ota... well, Ota (an innocent spelling error from the calligrapher who painted the names) should have read Otto, who was their brother, another great-uncle. All three were siblings of my grandpa, Dr. Rudolf Rieden; Emil was his father. And all, I later discovered, lived with my dad, Hanus Rieden, before he fled to England from Czechoslovakia in March 1939, only a week before Hitler’s troops arrived in Prague, part of an elaborate and desperate escape when he was aged just eight. He never saw them again.

How could I have been ignorant to their fate all this time? Why didn’t my father tell me? I turn back to the writing on the wall, now feeling ownership, but still incredulous. Next to each name, dates of birth and death are carefully painted. And as I push my brain to work out their ages, tears start to roll down my face.

I always knew our family was different.

For a start, while we lived in the heart of commuter-belt Surrey, on London’s outskirts, both our parents were only children and our grandparents lived in other countries—Mum’s parents 17,000 kilometres away, on the other side of the world in Australia; Dad’s trapped behind the Iron Curtain in Eastern Bloc Czechoslovakia. Our Australian grandparents, Flo and Roy, came over every few years in a big flourish.

But Rudolf and Helena were inaccessible, shadowy phantoms whom I imagined huddled under blankets, speaking in foreign whispers, always looking over their shoulders. We had one of their blankets—smart, camel-coloured with Rieden embroidered in bright-red chain stitch in the corner. I used it occasionally as an extra layer in winter. It was only decades later that I discovered this was one of the few remnants from home they were allowed to keep with them when they were imprisoned for three years in Theresienstadt concentration camp, north of Prague.

Rudolf died when I was barely a toddler, but Helena was constantly in my thoughts, rattling around my head. I was told she had come over to see us when I was almost three but then had to go back to Prague, beyond reach, again.

I knew that she and Grandpa had been through a really tough time in the war, and that they’d managed to smuggle Dad out to England before the Nazis deported them, which is why he was here with us and they were there, but he never went into details. I always thought it was strange that they didn’t come with him, and the answers I was given didn’t feel right somehow.

Evidently, like many Czech Jews, they thought the Nazi threat would be over in a matter of months and they would all soon be reunited. They were wrong. They ended up being stripped of the comfortable life they knew: Grandpa’s job with the government, their flat in Prague, holidays in the mountains. And, along with approximately 155,000 other Jews, they were sent on trains to Theresienstadt. Unlike most, they survived. How they managed this and what went on in that place was never discussed.

Nor was why they didn’t come back for Dad after liberation, something I never understood. He was their only son, serious-minded Hanus.

I thought if I could squeeze behind that Iron Curtain, reach Grandma and bring her over then we could sort it all out. I was told that Dad couldn’t go to his mother now because the Communists probably wouldn’t let him out again and he would never risk that—we were too precious to him. Whenever I brought it up he seemed genuinely fearful that his life might be snatched away.

As I grew older I would regularly berate my parents for not providing me with relatives. It became a family joke, one I trotted out like a bratty child. I had no idea that there had been relatives—so many—but they had all been murdered, 16 in total. It must have cut deep for Dad when I moaned about a lack of extended family. But still nothing was said.

When I pressed further, Mum did tell me that Dad’s wider family had been killed in the gas chambers, but no names were mentioned, no stories told.

Dad’s memories of Prague were about going to coffee houses with his mother; listening to classical music, eating bread dumplings and sauerkraut. He showed me a photo of him skiing in the mountains—a tiny boy in a woolly hat on wooden skis—and I was sure he said they had a family house somewhere in the countryside.

When I say I had no relatives it’s not entirely true; there were people, some we even called aunts and uncles. They called my father Hans or Hoss rather than John, the name we knew him by and it was an undiscussed fact that various strange Eastern Europeans were surrogate relatives to our nuclear family.

They were fellow Prague refugees—Annalisa, Theo and Klaus—all with strong accents. None of them discussed their past in any real detail; all were measured in what they revealed.

We knew they had been together in "The Mission" with Dad. This was a curious children’s home called The Barbican Mission to the Jews, where Dad was raised. The children had arrived there by a sort of religious kindertransport run by an evangelical preacher who had personally saved 68 Czech Jewish children from Hitler on the proviso he could convert them into Christians. Dad didn’t talk about this place much either.

But unlike Annalisa, Theo and Klaus, my father’s accent was almost imperceptible, and so I always assumed his story was very different from theirs and somehow less tortured.

I was wrong.

On the night before Dad died, in 2006, when we were all sitting around his bed with his favourite Mozart sonata playing, he looked straight at my eldest brother, his firstborn, and said in a clear voice: "The plane is in the hangar." He was hallucinating, morphine and cancer playing tricks on his brain. But what was he talking about?

Was this the plane that had taken him away from his parents and his homeland in 1939? I have a photograph of Dad, aged eight, climbing the stairs of the KLM (Royal Dutch Airlines) charter, a little cloth knapsack on his back. Was he going back to that pivotal moment when his life changed forever?

My investigations uncovered far more than I imagined. What I found was shocking, revelatory and deeply personal. It started to become a pilgrimage to remember my kin, to pay homage to their stories. I headed to Czechoslovakia and Poland to seek them out, to follow in their footsteps.

In my research I came across letters from my grandparents sent to Dad’s guardians in the Mission just after liberation and a locked box in the British National Archives with Dad’s name on it: John Rieden. It was locked in 2012 and was intended not to be opened until 2040. I had to lodge a Freedom of Information request to gain access to it, and in the 172 documents inside that box my father’s struggle was laid out.

This is an edited extract from The Writing on the Wall by Juliet Rieden, on sale now.

You Might Also Like