One Way to Reintroduce Wolves? Listen to the Voters.

This article originally appeared on Outside

When reintroducing wolves, where should you put them? A new study conducted by Colorado Parks and Wildlife suggests a simple solution: track the vote.

The plan: Reintroduce wolves in areas where voters support them.

Why wolves matter: Restoring wolf populations is a proven, cost-effective way to ensure deer and elk populations remain healthy, make forests more resilient to fire, capture carbon emissions, protect biodiversity.

What's the catch? Republican lawmakers often spread fear of big, bad wolves. By reintroducing the species only to areas that voted for them, this proposal seeks to ease locals' acceptance.

What's next with wolf reintroduction? Modeling wolf travel routes and destinations is essential to minimizing conflict, post-reintroduction. Should the initiative prove successful, it might make it easier to bring back wolves to more places.

Back during the November 2020 election, Coloradans voted on Proposition 114, which asked them whether they wanted wildlife officials to reintroduce wolves to the state's western mountains by 2024. It passed, but only by the slimmest of margins: 50.91 percent of votes were for the reintroduction, and 49.09 percent were against it.

That wolf reintroduction proved a controversial ballot measure is no surprise. The species has become a focal point of political divide in the wider culture war between Democratic and Republican politicians. Democrats acknowledge the science demonstrating wolves can bring ecosystems damaged by humans back to health, and create other ecological benefits, with only the slimmest amounts of livestock depredation. Republicans say wolves are a menace to livestock, pets, and humans, and they promote most plans that extirpate wolves from the landscape, sometimes by stoking fear and lying.

Given the controversy, why keep pushing for reintroduction? A recent paper published in BioScience found that wolves can help improve access to clean water, reduce the severity of wildfires, help forests capture more atmospheric carbon, and improve overall biodiversity and the population-wide health of the ungulate species they prey on. And wolves provide those benefits naturally, without human involvement.

But don't wolves kill livestock and hurt rancher's bottom lines? In Idaho, where wolves were reintroduced in 1995, the species is responsible for an average of 113 livestock deaths per year. That represents 0.004 percent of the state's total population of cattle and sheep. By comparison, the state loses about 40,000 heads of cattle each year to non-predator causes, like bad weather.

In Idaho, the state government recently ordered that $590,000 be spent hiring contractors to kill wolves and reduce their statewide population by 90 percent. That number will pale in comparison to the money and man hours federal and state agencies, researchers, and advocates have spent working to restore the species over the last 28 years, and to the ecological harm it will reap across Idaho's mountains.

As Idaho funds the killing of its wolves, how does Colorado Parks and Wildlife hope to find success with its own reintroduction? By reintroducing wolves only in districts that voted yes on Prop 114.

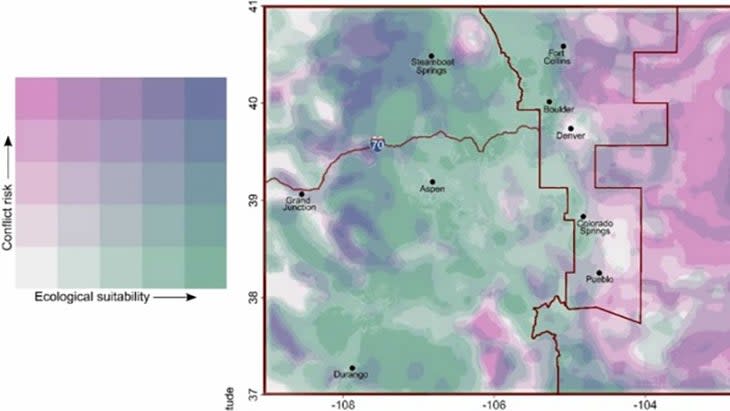

Mark Ditmer, the lead author on Colorado's wolf study, tells Outside that the research provides an unprecedented level of data on wolf tolerance. His approach in modeling areas suitable for wolf reintroduction could then be incredibly simple. He mapped out areas capable of naturally supporting wolf populations, then cross referenced them with voting results.

The result is a small swath of the Rocky Mountains running from north of Vail, south of Telluride, west to Montrose, and east to the outskirts of Boulder. Book a ski trip to Colorado in a few years, and you might also get an opportunity to see wolves in the wild.

Ditmer notes that votes for or against the reintroduction typically tracked along party lines, but in areas where elk hunting is particularly popular--around Steamboat Springs, for instance--political affiliation was less of a predictor. While wolves cannot be scientifically proven to reduce hunting opportunities, and can be shown to improve the health of elk populations, hunters often blame wolves for an unsuccessful season.

The plan is still just a proposal, and officials have not finalized exactly where wolves will be released.

Plus, reintroduction sites are only part of the equation. Voters may be able to track tolerance for the initial release, but wolves can travel up to 30 miles per day, and while dispersing to find mates, can travel over 1,000 miles. They will easily cross boundaries between voting districts and even states.

Ditmer acknowledges that, and says he's already working on a followup report, analyzing likely routes and destinations for wolf travel, with the goal of giving state and federal agencies the tools they need to plan conflict avoidance measures.

It's way too early to judge Colorado's wolf introduction as a success or failure. But one thing it is giving us is a new method for modeling tolerance. As the need for wild wolves increases with the converging disasters of climate change, biodiversity loss, and mega-fires, planning reintroductions according to voter preference could prove a valuable tool.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.