One man tackles the entirety of classical poetry – and triumphs

The heart of the reviewer can sink upon receiving a doorstop titled something like The Penguin Book of Greek and Latin Lyric Verse, and weighing in at a thousand pages, including the translator’s preface, notes on meter, biographies of poets, notes to the poems, as well as an afterword by a Very Important Classicist. Clearly this has been a labour of love – Christopher Childers spent over a decade on this tome (“a sort of personal odyssey, it has detained me for 10 years now”) – or maybe even a love of labour. That anyone would even attempt to sit down and translate a significant chunk of all Greek or Latin lyric poetry, and cram both the Greek and Latin poems into one volume is, let’s face it, a little daft. But it is an inspired and enlightening lunacy. It is rare to be able to say, as a reviewer, here is a work of staggering ambition, exceptional accomplishment, and surprisingly pleasant reading, but here we are.

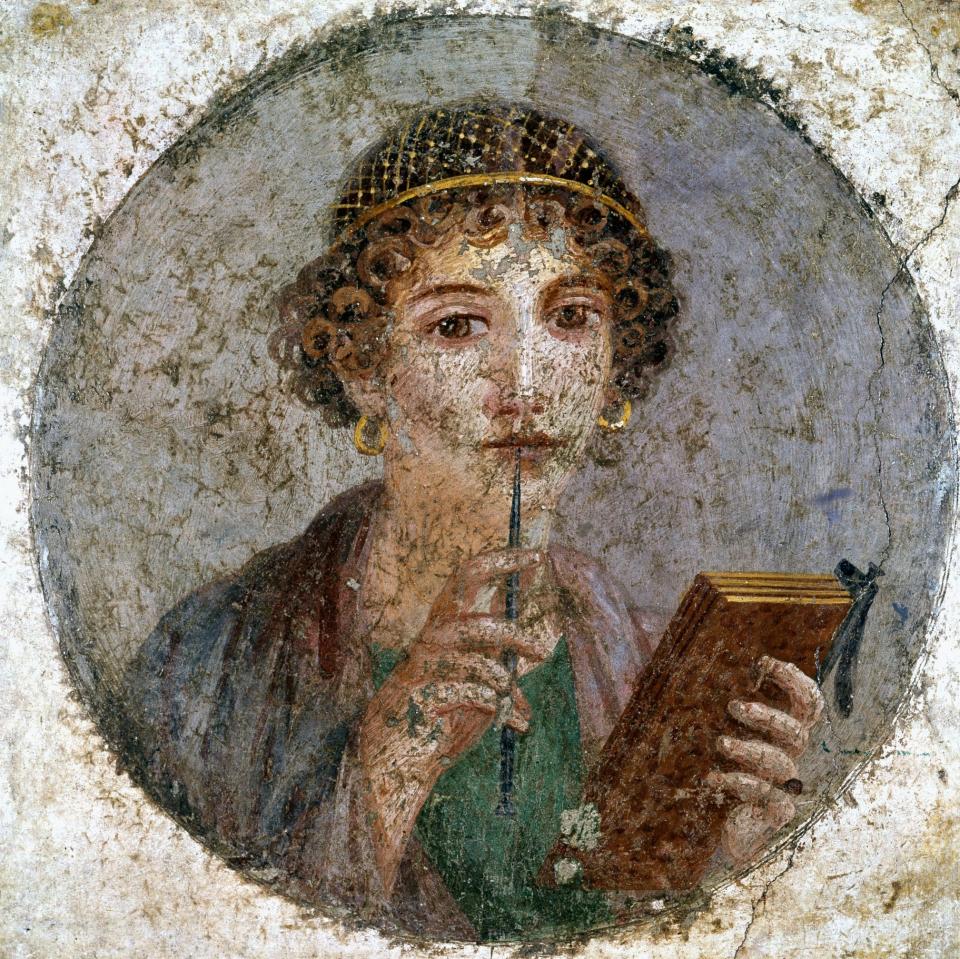

What is lyric poetry? It’s hard to define except by negatives, and, as Glen W Most points out in his afterword, does not mean quite the same thing to us as it did to the ancients, for whom it was narrower in technical approach and broader in occasion. It is not epic poetry, not didactic poetry, not drama. It is associated with the first person (singular or plural), and subjectivity, but even the most private Greek lyric was intended not to be read silently on the page, but to be heard, to the accompaniment of the eponymous lyre, in company – often the fancy upper-class drinking parties known as symposia. As such, ancient lyric poets had more in common with the contemporary singer-songwriter (and writer of “lyrics”) than the lyric poets of the Romantic era. Nearly everything that passes for poetry in the modern or contemporary world is, for all intents and purposes, lyric. Few now are the poems that explicate, for instance, crop rotation, the motions of constellations, or poisonous snake bites. For the didactic DIY, a Youtube video does the trick. For long narrative we tend to look to novels, for drama to movies or bingeable Netflix series; none tends to be written in verse.

The risk of a single translator rendering many poets might be a homogenising flatness, but Childers retunes his instrument for different effects, adding a string, slapping on a capo, going electric or harmonic. Perhaps most originally, Childers aims to get us to perceive connections across not only centuries and poets but languages. Different metrical patterns are associated with different subgenres or “vibes”, and Childers is programmatic in his rendering of said patterns. Elegiac couplets (a dactylic hexameter followed by an elegiac pentameter), for instance, a meter associated with “inscriptions and epitaphs,” “love elegy” and “Greek and Latin epigram,” are always translated into rhymed iambic pentameter. Sapphics, associated with hymns and prayers, are translated into quatrains with an ABAB rhyme scheme.

Childers consistently, and sometimes brilliantly, turns out translations that also work as English poems. Even in cases where a poem already exists in a famous translation (eg Callimachus-cum-Corey’s “They told me, Heraclitus, they told me you were dead”), Childers manages to both produce a solid new translation, and wisely wink at the famous version:

When I heard, Heraclitus, you were dead,

I thought of all the suns we’d talked to bed

Those nights, and the tears came. Dear guest, I know

That you were ashes long and long ago,

And yet your nightingales are singing still:

Death kills all things, but them he cannot kill.

Childers isn’t afraid of wild register swings. There are swear words, occasional baby-talk (“widdle”), some retro slang (“payola”), well-deployed foreign words and phrases (“capisce?” “froufrou canapés”), pop-culture references (“our Mr Big”), and a sprinkling of ten-dollar words such as “corposant”, “anadem”, “galingale”, “irriguous”, and “cerements”. Very occasionally a rhymed couplet can come across as a little too pat (“Leophilus is leader now, Leophilus has sway, / it all rests with Leophilus; Leophilus, horray!”), but especially in more complicated stanzas, Childers brings all his poetic chops to bear. Here’s Childers channeling Pindar (arguably the greatest, albeit least accessible, of the canonical Nine Lyric Poets) and his famous opening of the first Olympian Ode, the Pindaric Ode being one of the most fiendishly challenging lyric verse forms:

Water is best, while of all riches, gold,

like fire in the dark, shines well apart.

But if it’s games, my heart,

you want to hymn, what star could you behold

more warm or more unrivaled in the air

than the bright sun

or what contest compare

to Zeus’s at Olympia? Not one.

Some will notice that Latin poets make up much less of this book than the Greeks. This has partly to do with the longer sweep of classical Greek literature, but also survival bias: we just have more of the Greek corpus. Nonetheless, the Romans hold up. Childers brings home the importance particularly of Horace, not only on later Latin authors, but on all Western poetry that follows, more or less up to the present day.

Childers’s elegant prose wears its learning lightly, and is often stealthily hilarious. “Aristotle mentions, unpleasantly, that Alcman died of pubic lice.” “With the fleet becalmed there in the harbor by the anger of Artemis, Agamemnon was forced to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia – a solution which proved expedient for the war effort, but had a bad effect on his marriage.” The notes also point us to allusions to these poems or translations of them in the whole sweep of Anglophone poetry, and beyond, making this a relevant sourcebook for readers of Western poetry of any era.

This book would make an excellent gift for anyone interested in classical literature: it practically amounts to a degree in classical literature in translation. Yet the recipient will need to be able to handle “mature language and themes”. F-bombs abound (not gratuitously; blame the Greeks and Romans), and sex is popular in hetero- and homosexual variations. In Lyric, the scabrous rubs shoulders with the sublime, the scatological with the sophisticated, the martial with the venereal.

What ends up being most surprising here is that sometimes what seems at first glimpse to be the most derivative genre or poet ends up being an inflection of absolute originality. We can see here how Theocritus’s pastoral idylls seem to spring up out of nowhere. Or as Childers points out of Latin literature, it “has its origins in translation from Greek” and that “to modern habits of thinking, this fact may call the originality of Latin literature into question” but “The truth is that translating a foreign literature was, in the third century BCE, perhaps the most original thing the Romans could have done.” For the Greeks, literature was precisely what one did not translate from another culture. Likewise, this anthology of Greek and Latin literature collected and translated by Christopher Childers might seem at first like an old-fashioned, conservative undertaking, but proves to be itself a work of striking originality, resulting in a fresh, new understanding of what it is to talk about, read, or to write lyric poetry. Or, as we tend to call it, “poetry.”

AE Stallings is the Oxford Professor of Poetry; her latest book is This Afterlife: Selected Poems. The Penguin Book of Greek and Latin Lyric Verse, translated by Christopher Childers, is published by Penguin Classics at £45. To order your copy for £40, call 0808 196 6794 or visit Telegraph Books