Once unwanted, these lucky dogs were rescued. Now they're learning to rescue others.

Toby was a misbehaving chocolate Labrador retriever. He wanted to work, but he was stuck at an animal shelter.

Then, all of a sudden, he was in the running for a top-flight dog career – with all of the related perks.

Just being considered for K9 training was quite a feat for a dog like Toby.

No one had bred him for search and rescue work. And his background included exposure to a bunch of other badly behaved dogs, two of whom were part wolf. The animal hoarding episode didn't look very good on Toby's résumé.

But that sort of thing wasn't a deal-breaker for the man who controlled Toby's destiny. In fact, Matthew Zarrella was known for getting the very best from dogs of humble origins and unknown pedigree.

What helped even more was that Zarrella, a former state police sergeant and dog handler, thought Toby was energetic enough for K9 work. As Zarrella saw it, Toby actually needed such a job.

"I don't care what they look like," Zarrella says. "All I care about is, will the dog work?"

Toby surely would have panted with wild enthusiasm and anticipation if he had known about the lives of Zarrella's previous draft picks: The fame! The travel! The treats!

But dogs cannot know about such things until they experience them. And life doesn't always repeat itself like that. Draft picks don't always make the team.

A more subdued retirement life after legendary K9 feats in the state police

Zarrella, who had founded Rhode Island's state police K9 search and rescue program in the 1990s, was still quite active in dog training around the time he met Toby late last year.

But he wasn't exactly the same guy who had sprinted through swamps to find missing people as a young state trooper.

It had been a long time since Zarrella had relied on the noses of his own police dogs to find human remains in settings across the United States and beyond, as far away as Colombia and even Vietnam – where, on one occasion, he had helped searchers find the remains of a U.S. military pilot who had been missing in action since 1966.

He no longer wore a state police uniform. He was a retiree in his early 60s.

If this K9 sequel were going to happen, it would need to follow a different path – by necessity.

Tracking a different type of trail

Dog handlers and certified search dogs who want to volunteer have an option in Rhode Island if they can qualify. And they don't have to be sworn police officers.

Zarrella himself had helped create this pathway early in his police career, fostering cooperation between state police and volunteer K9 teams and paving the way for an organization known as Rhode Island Canine Search and Rescue.

But at this point in his life, Zarrella, of North Kingstown, just wasn't sure if he was ready to do all of the hard work of training and handling his own certified search dog, day in and day out, once again.

Initially, he agreed to spend some time with Toby to help correct the dog's misbehavior. He assessed the Lab's health, size, strength and temperament. Toby's "drive" – his readiness to either play or hunt for prey – was key.

Looking back, Zarrella recalls, "There was a little bit of a tinge in me that said, 'I would like to get back in the fight.'"

From untrained K9s to celebrities

Zarrella had embraced that challenge quite easily and energetically as a young man in the 1980s and '90s.

He had left the Marine Corps, worked as a plumber's apprentice, and then joined the Rhode Island State Police.

He had also acquired a Greater Swiss mountain dog as a pet. He named him Hannibal.

Then, in 1991, a crisis in Barrington snagged his attention. An entire family, Ernest Brendel, his wife, Alice and their 8-year-old daughter, Emily, had gone missing under suspicious circumstances. Human beings could not find them. Almost seven weeks later, a pet dog identified the spot of the family's shallow grave, convincing Zarrella that state police needed a search dog to help them find missing people and human remains.

With persistence and his own money at first, Zarrella provided Hannibal with some search dog training. It was a gamble.

Then, the two of them set out one day to track down a missing child in Burrillville. The boy hadn't been seen in more than 30 hours, Zarrella recalls. Hannibal found him. Soon after he joined the state police.

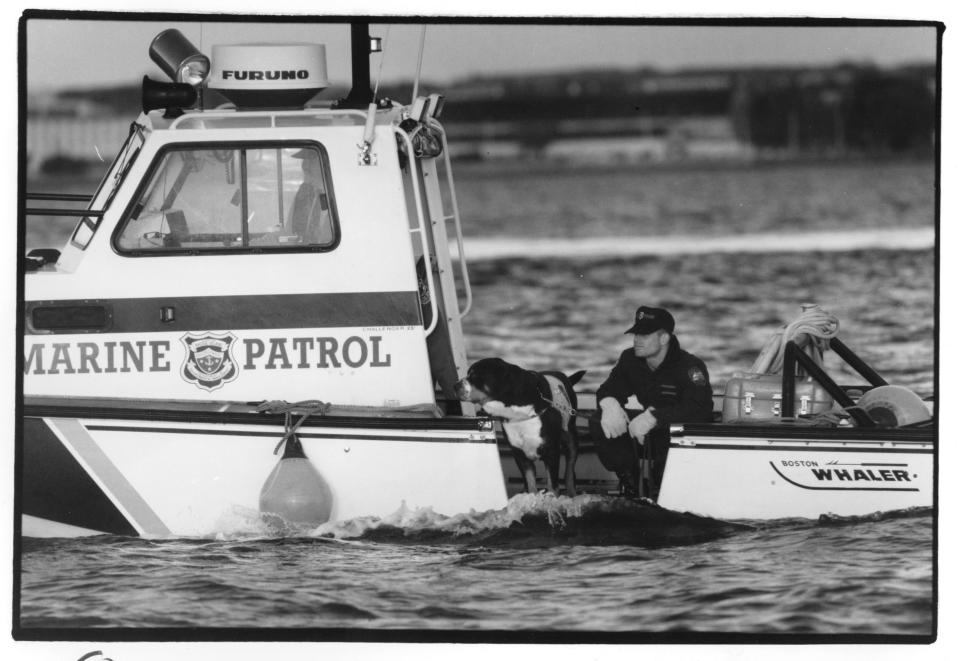

The dog would go on to participate in 101 searches across the Northeast. He would find two missing people. Hannibal could sniff corpses buried in dirt. From the deck of a boat, he could detect a body sunk in the depths of Block Island Sound. He would recover 11 bodies.

He was featured in People magazine. He appeared on "America's Most Wanted," "48 Hours," "Unsolved Mysteries" and other television shows.

Other hero dogs followed in Hannibal's footsteps. Both Maximus, a German shepherd who had been deemed aggressive and left at the pound in Scituate, and another shepherd, Panzer, had accompanied Zarrella in Vietnam. A third shepherd, Ava, had become the state's first disaster dog. She and Gunner, another Greater Swiss mountain dog, were both giveaways. Buster, a bomb-detecting dog, was a hand-me-down from the U.S. Marines.

On paper at least, none of these dogs had the established pedigree and grooming that many police organizations pay for when they buy untrained K9s from specialized breeders.

This applied even to Buster, Zarrella says. The highly trained work dog came from a breeder and had served two tours with Marines in Afghanistan.

But Buster had been trained for off-leash military settings, which aren't the same as police settings. For this reason, Buster "flunked out" initially and had to be retrained to work on a leash, Zarrella says.

Of course, the list isn't complete without mentioning Ruby – although Zarrella wasn't her handler. Ruby would become so famous that she was depicted in "Rescued By Ruby," a Netflix original movie.

As a state police sergeant, Zarrella had evaluated Ruby, a border collie and German shepherd mix, about two hours before a veterinarian was expected to euthanize her. Zarrella brought Ruby into the state police and assigned then Trooper Dan O'Neil to handle her.

How Rhode Island Canine Search and Rescue was formed

There was something else Zarrella had accomplished in addition to developing the K9 search and rescue program at the state police. It had bearing on his situation with Toby.

He had formed an entity known as Task Force 2 – a volunteer contingent of K9 handlers, search dogs and searchers.

The volunteers were ready to deploy and provide assistance in certain types of missing person emergencies. Having a group of K9 search dogs makes it possible to sniff through vast expanses of land far more quickly.

Several different volunteer groups were part of the task force initially, Zarrella says. Rhode Island Canine Search and Rescue was established in 2004.

"We are an all volunteer group and are dedicated to saving lives and providing closure for families whose loved ones have been missing for whatever reason," says a statement posted on the group's website.

Its mission is "to serve so that others may live." Its founder, Jim Rawley, says the group participated in at least 30 searches last year.

Such undertakings are more popular in the South and Midwestern United States, and they aren't used as often in New England, Zarrella says.

Turning rescue dogs into rescuers

The group's overall search capacity is governed in no small part by how many K9 search dogs it has. But the nonprofit organization and its volunteers don't have unlimited resources.

Not every volunteer can afford to buy an untrained puppy with the most desirable breeding history and grooming for search and rescue. The cost of acquiring such a dog ranges, but the National Police Dog Foundation's estimate is about $8,000. That covers the cost of moving the dog, often from Europe, but it does not cover the training to come.

This is where the approach that defined Zarrella's K9 career has been helpful.

Working with a dog of unknown origin is a way to avoid some of the up-front acquisition costs. It can involve a lot of extra time and love. But not always. Also, Zarrella's experience shows that some unwanted dogs, or so-called "rescue dogs," have what it takes to perform at the highest levels of K9 search and rescue. Dogs that were once rescued themselves can become rescuers.

What happened with Toby?

On a recent Sunday morning, the volunteer group is on the former Ladd Center campus – a state property near the Rhode Island Fire Academy in Exeter.

Their trailer serves as a rolling headquarters. It offers some shelter and supports the group's radio system, which has its own frequencies. The trailer also carries other tools, including a computer system that maps out terrain into grids and tracks K9 teams on a large monitor as they move through. If someone makes a find, there won't be any confusion about where a dog is, says Rawley.

Outside the trailer, in a simulation, handlers and their dogs are searching for live people who are hiding in the woods.

Marjorie Aubee, a 57-year-old school bus driver who lives in Richmond, follows Eloise, her 7-year-old mixed-breed pit bull.

Eloise's mother had been pregnant with Eloise when an organization in Georgia rescued them both in 2017. In 2020, under Aubee's tutelage, Eloise demonstrated enough proficiency in finding live people and corpses to achieve certification in both disciplines from the International Police Work Dog Association.

In late 2022, Eloise helped clear a sector during a search that ultimately recovered the body of a missing 33-year-old man, David Craig, at Carr's Pond in the Big River Management Area in East Greenwich.

Now, slowly, in a methodical style, the search dog is weaving through forest near the fire academy. She completes the live-find exercise to effusive praise.

Not long after this, Zarrella's SUV rolls in. He's with Rosie, a basset hound mix, and he has Toby with him, too.

Toby achieved certification as a cadaver dog in January. He hasn't certified at live finds yet, but he likes it, apparently.

"Toby is learning much faster than I expected," Zarrella says. "He just sucks it up."

Zarrella acknowledges that Toby has a counter-surfing habit that needs attention. On this morning, the dog had stealthily scored seven cookies for himself, Zarrella says. Toby, he says, has an "excellent work ethic."

At the weekly training session, Toby's first challenge is to find some human material (which typically comes from medical sources) hidden underground near some fallen tree limbs.

He signals his find by sitting down. The next challenge is similar but just a little harder.

After this, the handlers give Toby a new test. For the first time, he has a chance to track a scent that emanates from an underwater location.

The K9 handlers have submerged some odor-dispensing capsules in the water of a flooded parking lot. Eventually, after extensive splashing, the Lab finds what remains of the original capsules. He sits down on some dry ground nearby.

"That's a goooooood boy," Zarrella says.

Toby is still learning – but now he has a job. Zarrella is still a police retiree – but now life isn't quite as tranquil.

"It's a great feeling to be back," he says.

This article originally appeared on The Providence Journal: How once unwanted RI rescue dogs are trained to become K9 rescuers