This old restaurant was a Kansas City favorite … until everything (literally) fell apart

Uniquely KC is a Star series exploring what makes Kansas City special. Are you feeling nostalgic for a Kansas City area restaurant that closed years ago? Share your memories, and we may write about the place in a future story.

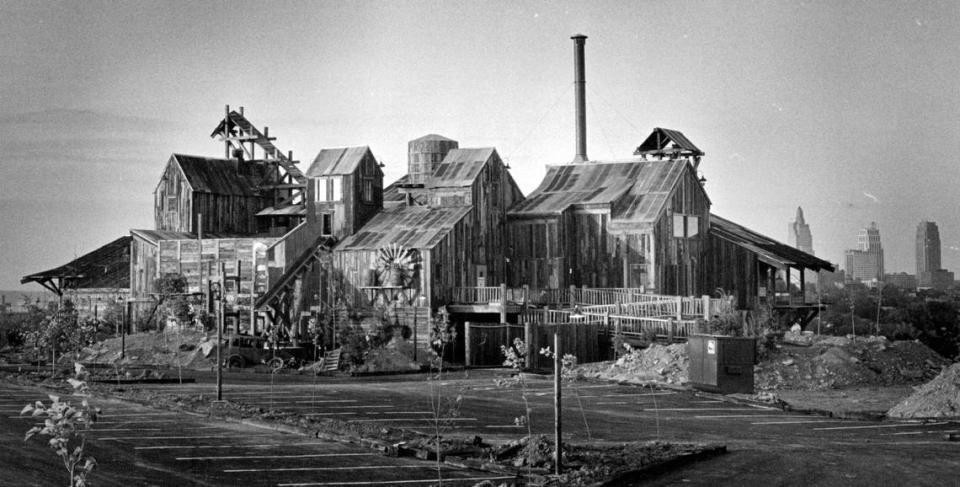

It was something to behold.

A mansion built of weathered wood, seemingly nailed haphazardly together. Half of it stood on crisscrossed stilts overlooking the Kansas City skyline.

The structure leaned forward on a hill, as if one push would send it tumbling.

“Ramshackle chic,” as one Kansas City Star reporter described it in 1980. Somewhat prophetic words, though at the time its makers insisted the building was only designed to look shabby. They fully intended Baby Doe’s Matchless Mine to stand for years to come.

Never mind the rainwater that occasionally dripped from the ceiling. Or the cracks that spiderwebbed across the kitchen floor. Or the beams that drifted further and further apart.

Tim Phillips, a former waiter at Baby Doe’s, brought up the old Kansas City restaurant in conversation years later.

“The one that fell down the hill?” someone piped up in response.

Yes. That’s the one.

But as its many fans would say, it was fun while it lasted.

One of its frequent visitors, Stephen Hawks, recently wrote to The Star hoping to find out more about the place. He remembers the dazzling skyline views and nights he and his future wife spent on the dance floor.

Opening day hiccups

In 1979, Baby Doe’s Matchless Mine was erected on a bluff 150 feet above Interstate 35 at the Cambridge Circle interchange. It stood just east of the state line so its downstairs club could serve copious amounts of alcohol, avoiding the stringent liquor laws Kansas had then.

At the time, the mine shaft-themed restaurant was expected to transform the Cambridge Terraces area southwest of downtown into a booming development.

“This restaurant is the start of a development that will include motel facilities, other restaurants, office complexes …” a developer told The Star in 1979. Though today, the area is relatively quiet, save a few office buildings. Perhaps the restaurant’s brief life is to blame.

California-based Specialty Restaurants Corp. had already opened Baby Doe’s restaurants in Dallas, Denver and Birmingham, Alabama, and was hoping to bring the concept to the Midwest.

The four-story building was set up to hold 300 diners, with an additional 200 in the basement club. (Which, Phillips said, could be quite rowdy in the evening.)

To create the massive structure, developers foraged the country for old barn wood. It was a $1.5 million project, though, as one Kansas City Times writer noted, it looked to be about 100 years old.

Things were almost ready to go in August 1980. The last rickety beam was in place, and reservations for opening day were set.

But days before Baby Doe’s debut, the sprinkler system still wasn’t working, and the Kansas City Fire Department told restaurant staff to call off the opening celebrations.

An omen? Perhaps. Or maybe pure bad luck.

“The cancellation forced restaurant employees to spend a good part of Tuesday on the telephone telling people, including (the mayor) and other city officials, not to come for cocktails, hors d’oeuvres, and prime rib dinner that were to have marked the christening of Baby Doe’s,” The Times (the former sister paper of The Star) chronicled at the time.

Phillips remembers.

“We were told, ‘OK, we’re opening tomorrow night,’ and then here comes the fire department up the hill,” he said.

Despite the hiccup, it did open about a week later. Then diners arrived in droves to chow down on crab legs and prime rib while marveling at panoramic views of the city.

Terri Lawson, who also worked there as a server, reminisced about the nights spent partying in the cavernous basement. She raved about the architecture and “really good” beer cheese soup.

“It was a special place,” she said. “People would celebrate birthdays, anniversaries, whatever.”

A petting zoo outside welcomed families ahead of lunch and dinner. She still remembers the little mule, Clementine, who brayed “hello” customers. (Mules were once used to pull coal carts in mines.)

A junked car from the late 1800s, early 1900s sat near the entrance.

“If somebody wanted a tour, we had to stop what we were doing and take them to each room,” Lawson said. “The floors were creaky, and it gave me the real feel that you were in an actual mine.”

Reviews rolled in, and despite the lively atmosphere, critics noted the food was lackluster.

“Only the atmosphere is matchless,” reads one especially brutal headline from The Star in 1981.

But it was certainly a popular place. Another article claimed wait times could be up to three hours in the first few months of its opening.

‘Hold on to the Matchless’

Employees were expected to be well-versed in the true history of Elizabeth “Baby Doe” Tabor, a Colorado socialite who rose to fame after senator and silver tycoon Horrace Tabor left his wife, Augusta, to marry the much younger woman. Horace was one of Colorado’s wealthiest men at the time.

Horace’s lucrative silver mine in Leadville — called the Matchless Mine — was the blueprint for each Baby Doe’s restaurant.

But the Tabors lost their riches after the price of silver plummeted during the Panic of 1893. They died paupers.

As the legend goes, Horace’s last deathbed plea to his wife was, “Hold on to the Matchless. It will make millions again.”

Keeping her promise, Baby Doe lived in a shabby cabin near the mine decades after Horace’s death.

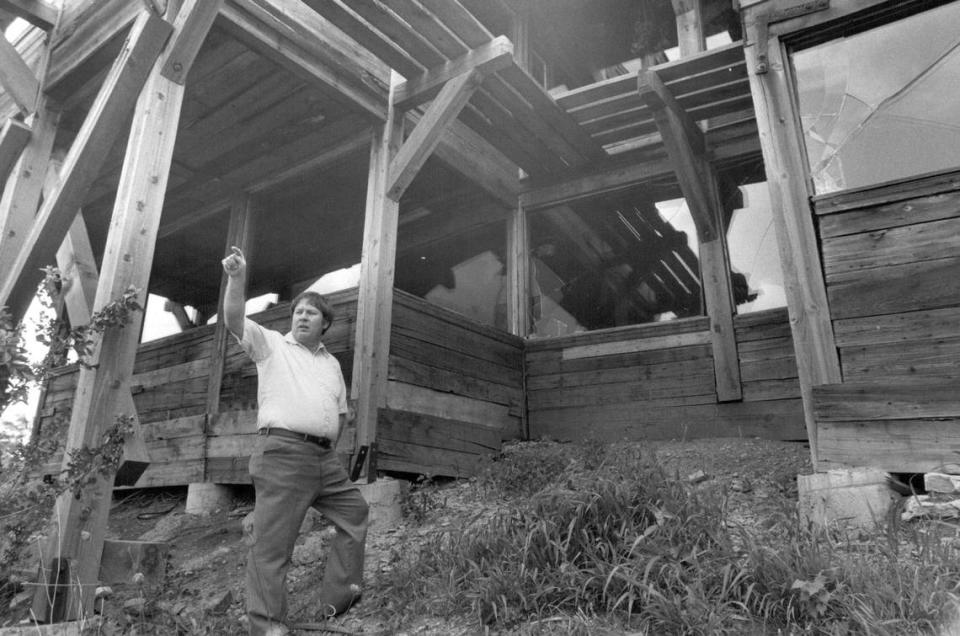

Much like the Tabors’ fortune, Baby Doe’s Matchless Mine was a powder keg waiting to explode. Toward the end of its run, employees began to notice that the beams holding the roof up began to move further apart.

Equally concerning was the rift that was growing in the kitchen floor. Then its back windows shattered.

Restaurant owners began to realize they were holding a lit fuse. On August 3, 1985, The Times reported the support beams had moved up to one-and-a-half feet apart in a week, partially separating the restaurant’s dining rooms from the rest of the building.

The shifting hill on which Baby Doe’s stood was to blame, engineers concluded, and it had caused $500,000 worth of damage to the restaurant.

Baby Doe’s closed down that week, though restaurant owners said they still hoped to reopen after making repairs. They had previously hoped to expand on the hill to accommodate more customers.

Owners held onto hope for months that, like Horace’s deathbed cry, the Matchless would make millions again. But the building was razed a year later.

In 1991, a Jackson County Circuit judge ruled that the restaurant’s owner, Specialty Restaurants Corp., owed the property owner, Dean Realty Co., $1.5 million for defaulting on its lease and failing to build the restaurant properly.

While other Baby Doe’s locations survived longer than Kansas City’s, none are still open.

Unless, of course, you count the real Matchless Mine in Colorado.

The rundown property where Horace made his fortune can be toured today, though visitors are prohibited from entering the mine shaft.

Too dangerous, its website notes.