Is It OK to Sell Breonna Taylor T-Shirts?

Jason Wess had designed for a few different brands before founding MoreJasonWess in May 2019. Most of his clothes featured the phrase “Don’t Give Up”—a slogan inspired by his mother’s advice—on t-shirts, trucker hats, and tote bags. While quarantined in Miami, Wess started to think about how that mantra applied to the Breonna Taylor case, and designed a T-shirt with the words “Arrest Breonna Taylor’s Killers” highlighted in purple and accented with stars. On the back is a phone number that provides updated information about the case before connecting the caller to local and state officials overseeing the investigation.

Wess pondered the ethics of selling the T-shirt for a while—“because I really didn’t want to be that guy”—before eventually deciding that the “biggest way I could reach people was to make merchandise that’s obtainable...someone could see someone else wearing it and it could go on and on. I made one shirt for me, and then I posted it and it was like a rain fall after that.”

But soon after his Taylor tee became available, Wess started hearing from people who wanted to know exactly what percentage of the total proceeds would be donated to the Breonna Taylor Go Fund Me, as promised on the website. “Once I’m done selling shirts I’m just going to tally it up and figure out a percentage that I can maintain at this point,” he said. “We’re still in hard times right now. I’m trying to figure it out myself.”

In the meantime, the constant questions about how much he’d be donating made him turn Instagram comments off. “It was just like, ‘you guys aren’t getting the purpose.’ The purpose is the statement to raise awareness,” Wess said. “I’m not trying to do this to get famous. I’m not in it for any recognition. I’m literally in it for awareness. If it’s gonna bring more eyes to the cause then I’m down for it.”

The ethical quandaries raised by Wess’ T-shirt—is it OK to sell merchandise commemorating a victim of police violence? What is the appropriate way to raise awareness, and what crosses the line into commodification?—are in some ways the same dilemmas that NBA players have been grappling with on a much larger scale as they consider whether and how to play basketball while doing activist work. They’re also part of a larger debate about the appropriateness of sharing Breonna Taylor memes on social media, with some claiming such memes are superficial and exploitative.

Players inside the bubble have used clothing to spread messages they feel strongly about—from Chris Paul advocating on behalf of Historically Black Colleges and Universities to Anthony Tolliver, Andre Iguodala, and Jabari Parker choosing to have “Group Economics” stitched across their backs. Some have also decided to honor Taylor and George Floyd with t-shirts that escalate awareness, blazon their feelings, and provide literal action items.

The independent designers who make the t-shirts are using their gifts to effect change the best way they know—but they’re also conscious that attention is being drawn to their brand because someone was killed, and dealing with that conflict in their own ways.

Soon after Wess’s Breonna Taylor T-shirt went on sale, representatives for Houston Rockets forward PJ Tucker reached out to ask how quickly Wess could ship one to the bubble. A day later, Tucker wore it to the arena. “PJ got it and hit me up instantly and was like, ‘I had to change up my whole outfit because I wanted to wear this,’” Wess said.

Jimmy Jensen can relate. Shortly before the NBA season shut down for the first time, the lifelong Kobe Bryant fanatic started his own clothing brand called McDowell’s—a long-held dream accelerated by Bryant’s death. He started by selling t-shirts that honored Kobe at cost “because I couldn’t profit off of the death of my idol,” and donated all the money earned to the Mamba & Mambacita foundation.

A similar feeling hit Jensen “like a ton of bricks” when he saw footage of George Floyd’s death. He knew he wanted to use his new line to raise money to fight police violence; the concept for a t-shirt came after he saw a photo of Floyd in his South Florida State College basketball jersey.

“That’s just what sparked the idea,” he said. “I had been wanting to create something for him. I was just thinking about what I’m best at and felt the right thing to do would be to put shirts out in the world that can raise money for the cause.”

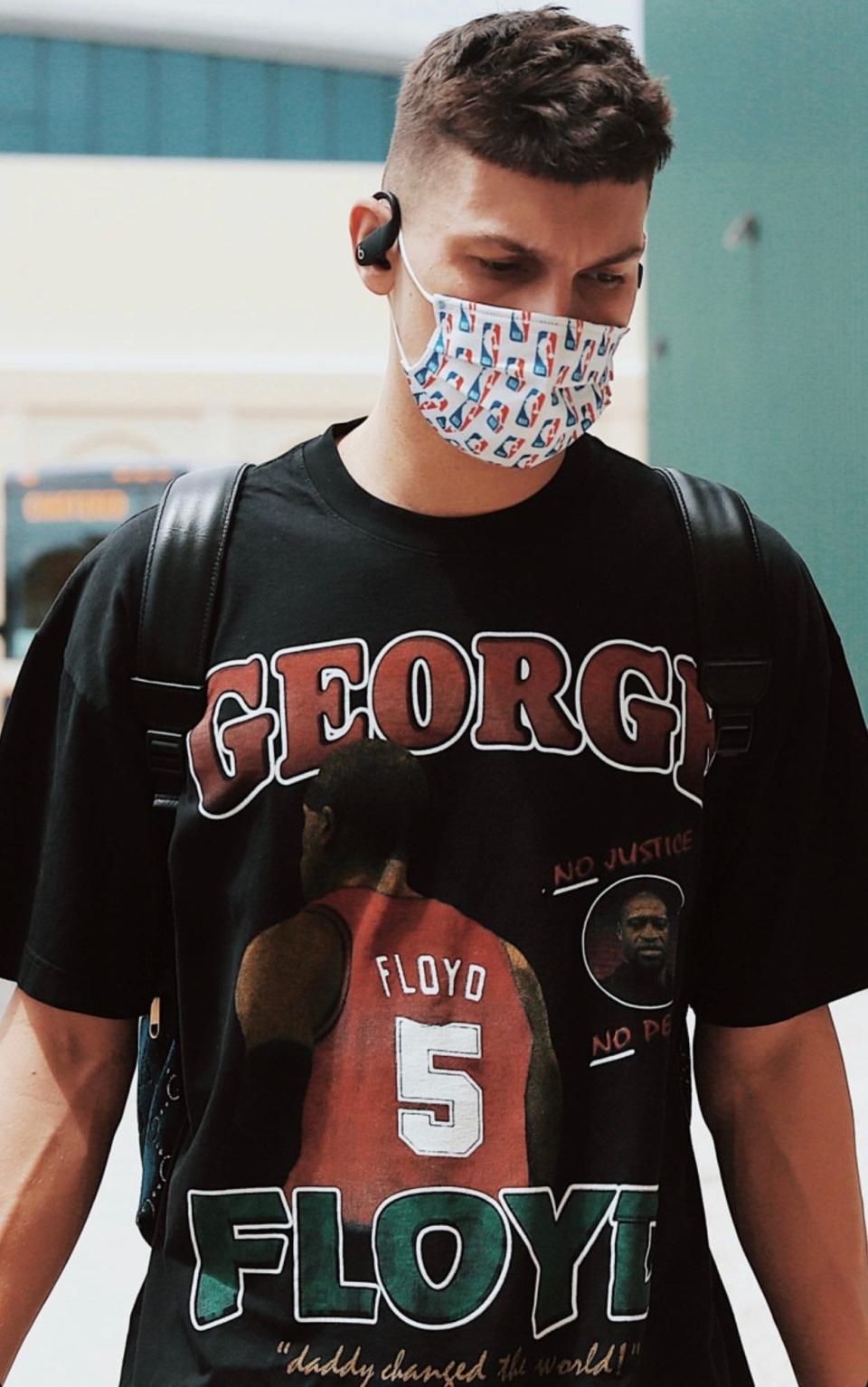

The shirt is black with George Floyd’s name spelled out in large red and green letters. Jensen used former NBA player Stephen Jackson’s body as a stand-in for Floyd—Jackson and Floyd frequently referred to each other as ‘twin’ after they met in the mid-90s. Jensen photoshopped out a few tattoos and had his brother tack a wrinkled number five onto the back of the jersey. Right beside this image is Floyd’s face, centered between the words “No Justice, No Peace.”

A little over a month later, as the NBA season was getting ready to reconvene in Florida, Jensen had an epiphany while listening to a podcast that mentioned the names of the Disney resorts each team would be housed at. So he folded several of his Kobe Bryant and George Floyd shirts inside bags marked with the McDowell’s smiling basketball logo, addressed them to a few players, and crossed his fingers.

Over the past couple weeks, James Harden, Jayson Tatum, and Kyle Kuzma have all been spotted in a McDowell’s printed t-shirt, and a few days ago, Miami Heat rookie Tyler Herro wore the one with George Floyd’s face on it.

Jensen says he’s “always trying to avoid cultural appropriation and things like that,” and is donating 100% of the proceeds to Black Lives Matter. He says he hasn’t encountered any direct criticism. The entire experience has been surreal, but seeing Herro in his Floyd shirt was particularly powerful. “It’s just cool because he’s a fellow privileged white guy, you know? He’s from Wisconsin,” Jensen said. “To see a guy like that and know that he’s exposing so many people to this image that might not see people in Breonna Taylor and George Floyd tees in their day to day lives, it’s just special, man, to hopefully have an impact on even one person.”

Nathan DeVaughn lives about five minutes from Nike’s campus in Beaverton, Oregon. Four years ago, after painting a picture of Lil Yachty on the back of a jean jacket and posting it to Instagram, the positive feedback gave him the idea to start a clothing customization business. In early 2018, he connected with Portland Trail Blazers guard CJ McCollum, who wanted some jackets. The two have kept in touch ever since, and when he heard McCollum speak up during a press conference about the need for Taylor to receive justice, DeVaughn reached out.

“I wanted to make a parody of the vintage rock band tees that are super trendy right now,” said DeVaughn. “Let’s play with that vibe and insert social justice and something that actually means something. I did the whole t-shirt, said ‘Hey would you wear this?’ He was like ‘of course, send it to me.’”

Despite the overwhelming response he received from people who wanted to buy the shirt McCollum wore, DeVaughn doesn’t mass produce his items. “A lot of people thought it was a screen printed t-shirt and that I could just ship them out,” he said. “I think it goes back to—this is my personal take—memeifying her, when I sort of throw it out there and sell it. I could obviously donate all the proceeds, but I don’t know, the line gets a little blurry for me, personally.”

Portland Trail Blazers v Brooklyn Nets

DeVaughn doesn’t rule out someday creating an item many people are able to purchase, but to get there he’d first want to establish a few ground rules.

“I’d want to make sure the family is OK with that, that it will not be perceived as a trend or something like that. I just want to make sure I'm very clear with it,” he said. “I don’t want to bash people who are making t-shirts and donating 100 percent of the proceeds and making money off of it. But for me personally and what I stand for, I just want to make sure I walk the line and get the sign offs and think about the decision before I blow it out with her face on a t-shirt for everybody.”

The expectations of what a t-shirt can and can’t accomplish in the fight against irrepressible iniquity should be tempered. They will not directly lead to jail sentences for the police officers who killed Taylor or Blake. They won’t abolish qualified immunity or decrease racial bias within the ranks of America’s police force.

But images can be powerful, expressive forms of communication. They’re also better than nothing. “In this game, you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t,” DeVaughn said. “Would you rather [NBA players] wear Gucci hats or Louis Vuitton, that just means nothing, especially at a time when everyone’s eyeballs are on them? Or would you rather wear something that actually starts a dialogue about something that’s important?”

Originally Appeared on GQ