Why NYC's Bike Powered Delivery Workers Are Taking on Big Tech

Sitting astride an e-bike wrapped in purple gaffers tape, Gustavo Ajche grabs the phone from his raincoat pocket and pulls up the Grubhub app as raindrops pool on the screen. It’s a gloomy Saturday afternoon in New York City. After a long week working two jobs, Ajche says, ordinarily he might go home; he’s done delivery for the apps long enough to know when it’s sensible to call it a day. But I’m here to learn the economics of delivery work, so Ajche holds out his phone: This order is offering $13. Should he take it?

Join Bicycling for unlimited access to best-in-class storytelling, exhaustive gear reviews, and expert training advice that will make you a better cyclist.

Ajche, who is 40, is the most visible spokesperson and organizer for Los Deliveristas Unidos, a campaign started in 2020 by app-based delivery workers to fight for safety protections and wages befitting their status as essential workers of the pandemic. On one level, their complaints are those of gig workers everywhere—a lack of transparency from their Silicon Valley employers, “flexible” jobs better understood as precarious ones. Yet the constraints of working in New York mean that deliveristas in Manhattan have little in common with Uber Eats drivers in Dallas or St. Louis. Unmanageable traffic, narrow roads, and a high premium on convenience have turned New York City delivery workers into the nation’s largest two-wheeled workforce. According to a city government estimate, nearly half of the 60,000-plus people working full time or part time shepherding takeout for the apps get around on e-bikes, accounting for the lion’s share of deliveries. One way to understand their fight for fair jobs is as a critique of a modern American city from behind the handlebars.

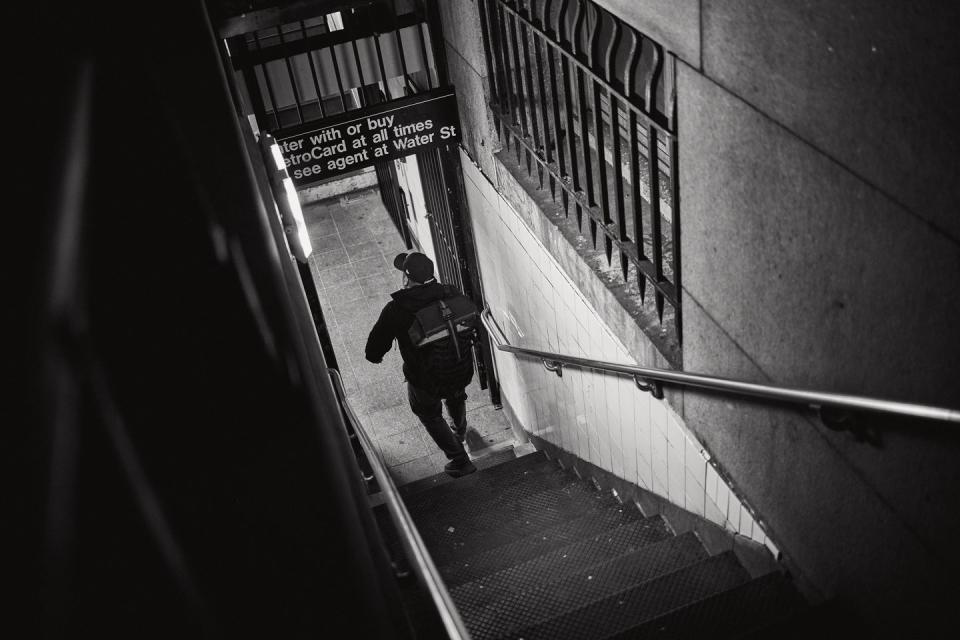

We head north through the financial district under a light rain, squeezing past cars stuck in gridlock, craning our necks to pinpoint the source of sirens echoing between towering office buildings. Compact and broad-shouldered, with a neutral expression and a single AirPod tucked under the hood of his coat, Ajche stands up in the saddle as we thread our way past the fruit stalls and paper lanterns of Chinatown, greeting fellow deliveristas with a nod and a beep of his electronic bike horn.

We jog west and emerge after about 15 minutes into the hubbub of Canal and Mott, a wave of pedestrians rising in the crosswalk against a wall of traffic. It is here that Ajche realizes he has a problem: Somehow, because of the rain or because of a software glitch, while his phone was in his pocket Grubhub had concluded that he had already picked up the first of two orders on the trip. We pull over in front of the plate glass window of a jewelry store while Ajche calls for help and explains several times over to someone on the app’s hotline that he can no longer see the address where he is supposed to pick up food.

Supreme Restaurant is visible under a red awning across the avenue, only about 75 yards away. Yet according to Google Maps and the traffic laws of New York City we still have close to a half mile to go, biking the long way around a quadrant of one-way streets. Grubhub’s interface is telling Ajche he has already fallen behind. It is 2:21 p.m. He “picked up” the food four minutes ago and should be cruising up First Avenue by now, well on his way to the East Village to pick up another order. After that, he has five minutes to drop off the first order and another eight to get to Peter Cooper Village, a maze of high rises on 21st Street, where the second bag of food is headed. The rain shows no signs of letting up.

To Ajche, the choice is obvious: With one foot on a pedal and one foot pushing off the pavement, he zooms across the crowded crosswalk as unobtrusively as he can manage, then dodges umbrellas as he darts along the sidewalk to 100 Mott.

It takes us a full hour to make both dropoffs, and by the time it’s over, we are both soaked through head to toe. Ajche turns off the app and we head back to his usual stomping grounds in the financial district, where his e-bike spends the night alongside dozens of others in the back of a basement parking garage. Of the $13 he earned, $9 was his share of the fees Grubhub collected from the restaurants, and $4 was tips. From the weight of the bags, Ajche estimates he was tipped $3 on roughly $100 of takeout in Chinatown, and a dollar for a single meal at a noodle place in the East Village. “That’s why I like working in this neighborhood,” he explains, referring to the financial district. “It’s rare that they only tip a dollar.”

The campaign to organize delivery workers in New York emerged out of mutual aid efforts at the start of the pandemic, when public sentiment for deliveristas was at an all-time high and legions of more stable jobs were at an all-time low. Their demands were simple: to be able to use restaurant bathrooms on the job, to be paid a reliable minimum wage, and to have some support, both from digital platforms and from the city government, to address the very real physical risks of spending 40-plus hours a week riding a bike on the streets of an American city.

Ajche got sick in February 2020 as the first wave of COVID-19 was crashing over New York, though the world hadn’t quite realized it. He recovered after a few days but ended up staying home for two months, still afraid to venture out. After a few stir-crazy weeks, Ajche reconnected with an old friend, Ligia Guallpa, who had launched a food bank through the Worker’s Justice Project, the nonprofit she runs out of a storefront in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. As Ajche spread the word about the food bank among his fellow deliveristas, friends who had never stopped working told him how the pandemic was reordering the delivery business. Early on there was plenty of work; even the money was good. But the distances were becoming impossible. You might have to bring takeout from Union Square to the Upper West Side via Times Square—a six-mile trek through Manhattan traffic that could chew up 45 minutes. Regular bikes were no longer up to the task. “So much was closed that people ordered and they didn’t care how far away it was.” With more and more of them riding $2,000 e-bikes on New York’s empty streets, deliveristas also became ready targets for robbery and assault.

As the pandemic wore on, Ajche saw the signs of a new kind of solidarity forming. On WhatsApp groups and another app that allowed smartphones to function like walkie-talkies, deliveristas trying to avoid crowds on the subway started coordinating their commutes over the bridges into Brooklyn and Queens at the end of the night. Later, the same groups began to function as an emergency response network for deliveristas in distress—share a pin and summon a peloton. William Medina, a Colombia-born deliverista working in Astoria, Queens, had his moped stolen in the winter of 2021. But he was able to message the group as it went down, and 40 deliveristas soon converged on the neighborhood where the thieves were making their getaway. They recovered the moped within minutes. Newly enlightened by discourse about essential workers, customers, too, seemed more appreciative of the people who left greasy, pungent paper bags on their doorsteps. Tips were better, sometimes accompanied by handwritten notes. “People now see us as doing something valuable, something worthwhile,” Ajche says.

But it didn’t change how bruising the conditions on the street had gotten. At the Worker’s Justice Project, Guallpa had led earlier organizing campaigns in domestic work and construction, and as she helped delivery workers connect with critical services and access cash assistance that the city government and foundations had set aside for immigrant workers, she began to see the contours of a campaign. Los Deliveristas Unidos held their first march in October 2020. They made flyers and signs and walked from 79th Street all the way to City Hall. “I think one reporter showed up,” Ajche recalls.

Over the next few months, the Worker’s Justice Project partnered with researchers at the Cornell University Institute of Labor Relations to conduct a wide-ranging survey of work conditions among deliveristas, with the goal of informing advocacy efforts and potential legislation. In a sample of 500 workers who ferried takeout for the apps—who were interviewed in Spanish, Mandarin, and Bengali—80 percent worked at least five days a week for a median pay of $12 an hour, the researchers found. And after accounting for the expense of keeping and parking an e-bike (many had bought their bikes with high-interest loans), it fell to under $8 an hour. Half of the workers had been injured on the job, but because they were independent contractors, they weren’t entitled to workers’ comp or the protections of a federal regulator like OSHA. Most of all, there was the sense that the apps were impervious to any kind of oversight, free to change workers’ ratings on a whim, shut them out of work, or constantly tweak how and how much they were paid.

After 18 months of lifting delivery workers into the pandemic pantheon, the path to creating new law in the City of New York cleared surprisingly quickly. In September 2021, Mayor Bill DeBlasio signed a package of reforms that guaranteed bathroom access, ensured that tips would make it to the workers who earned them, and set minimum delivery fees and maximum distances for each ride. But enacting the package’s most important provision would take much longer: Local Law 115 directed the city’s Department of Consumer Welfare and Protection (DCWP) to research and implement a rule that would actually set a livable minimum wage.

That rule was set to go into effect in December 2022. But when I shadowed Ajche at the end of April, 2023, the new arrangement had already been postponed by four months and counting, mired in a back-and-forth over the formula used to calculate workers’ pay—that is, whether to base it on the time they spent connected to the app or the time they spent on the move for individual deliveries. In May, delivery apps filed several overlapping lawsuits challenging the city’s rule. Finally, at the end of November, 2023, an appellate judge allowed the law to go into effect for the largest delivery platforms—Grubhub, DoorDash, and Uber—even as legal challenges remain pending. (A smaller company, Relay, was excluded.) Delivery workers in New York City must now be paid at least $17.96 an hour, and this rate will go up to $19.96 by April 1, 2025.

For the apps, delay has been its own reward: According to a city government estimate, each week the minimum pay rule was pushed back meant $15 million in lost wages for New York’s 60,000 delivery workers. That’s a bounty for the apps of more than $700 million over 11 months. When I asked Ajche to weigh in on the finer points of the city’s proposed rule, set forth in a 30-page PDF and argued in hundreds of pages of legal filings, he shrugged. “We just want minimum pay,” he said. In the spring, Ajche was convinced that the mayor was keeping council with Uber; still, he and Mayor Eric Adams stood side by side at a November 30 press conference after the order came down: “Our delivery workers have consistently delivered for us. Now we are delivering for them,” Adams said.

DoorDash and Grubhub shared statements affirming their support for deliveristas but declined to comment on the record. By requiring companies to compensate riders for idle time—when deliveristas are logged in but not on the move—the new rule encourages companies to make sure deliveristas are actually doing deliveries; it’s hard to justify paying someone to sit on a bike waiting for their phone to buzz. As a consequence, explains Uber spokesman Josh Gold, apps are likely to be more discerning about when and where they allow deliveristas to work, and even who is the right fit for the job.

Instead of an endless pool of laborers who log on for a few hours a week only to be disappointed by their earnings, the change will force apps to account for the conditions that actually make delivery work profitable, and hire accordingly. Ajche and Gold both agree that a delivery sector with a minimum wage rule is probably one with many fewer deliveristas, but Ajche doesn’t necessarily see that as a bad thing. “The apps will have a limit in how many people they can hire, but the people who are working will make a more stable living too,” he says.

All the same, the rule change hasn’t shifted the basic imbalance in the relationship. “Every time they turn on the app, they’re asked to sign this contract if they want to work,” Guallpa says. Uber and DoorDash both quickly rolled out interface changes that shifted tipping to the last step in each transaction, a move that Ajche sees as retaliation.

To really build power, Guallpa and Ajche agree, deliveristas will need to try to unionize: only a union contract could give them a structured, ongoing mechanism to address grievances and working conditions directly with the platforms. “What they’re saying is, ‘We‘re signing off on these conditions and the rules of the game… and we have no way to negotiate,” Guallpa says.

A deliveristas’ union is still a distant possibility in New York; unionizing a multilingual and largely undocumented workforce would take time, even without the headwinds of Silicon Valley’s bottomless capital. But delivery platforms have faced similar critiques and organizing efforts around the world. The complaints of Uber Eats drivers attempting to form a union in South Africa echo those of Danish workers organizing colleagues at the delivery platform Wolt, owned by DoorDash: insufficient pay and a lack of transparency. In November 2022, regulators in Tokyo opened the door for a collective bargaining agreement for delivery workers there, and in December 2023. officials with the European Union reached a provisional agreement that could lead to large numbers of gig workers being reclassified as employees, as opposed to self-employed contractors. Deliveristas in Spain are already classified that way, and as such enjoy health insurance and paid vacation time. As the visibility of Deliveristas Unidos has grown, Ajche says he has heard from workers in Guatemala and Costa Rica interested in organizing under the same banner.

Ajche grew up in an arid mountain region of western Guatemala, in a devout Christian family of leatherworkers who sold sandals and other handicrafts in Guatemala City, then moved back to the countryside when he was 12. Two years later he met a girl at a church retreat. They started dating and soon she was pregnant. Ajche’s parents were furious, but marriage was the only option. When the child was born, they kicked him out, and Ajche moved to his wife’s family’s home, in a farming community that grew tomatoes and vegetables. “Extremely tiring,” he says of his short-lived attempt to make a living as a farmer. After a year, desperate to support his young family, Ajche decided to move home and try and patch things up with his parents. When he learned his father’s trade, he began making trips to the capital himself, and soon began selling his wares for export as part of a co-op that operated out of the Guatemala City airport.

Then, one morning in the fall of 2001, a Tuesday, Ajche showed up with a load of leather goods only to find the airport in a state of quasi-shutdown. It was September 11. “Everything’s closed, there are no planes,” a colleague told him. Flights started up again quickly enough, but the export market would take years to recover. Ajche picked up work as a baggage handler, a grueling, physical job with low pay and long hours. By the time he got home after a 12-hour shift, ate, and rested, it was already time to go to work again. By the end of 2003, Ajche had resolved to leave. There were neighbors in the village with family in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, and after his father put the family home up as collateral for a $5,000 loan, Ajche joined a group of a dozen other young men for the monthlong trip north through Mexico. Arriving in New York, Ajche got a shared room in an apartment full of construction workers, and a lead through the Western Guatemalan grapevine about a job at a Chinese-owned kosher pizzeria on the Upper East Side. A cousin’s friend’s cousin worked there.

In those days, delivery was a bespoke offering, with each individual restaurant setting its own service area and hours according to its competitive niche. At pizzerias, the job was often split in two: A deliverista might spend part of each shift as a dishwasher and janitor, and then go out on a bike with an insulated pizza bag during the rush. Ajche still remembers getting bicycle lessons from the cousin who helped him find work—riding in New York is not for novices. He also recalls the humiliation of botching his first order: It was for two pies, already paid with a credit card over the phone, to a tenement in East Harlem. When he got to the address, he found a group of teenagers on the stoop, and held the pies out as a kind of implied question: Pizza? “Yes cousin,” one said, in Spanish. “The pizza’s for us.” When he returned to the restaurant, late, the exasperated owner said he’d been fielding calls from the actual customer, who lived upstairs.

As Ajche got settled, he started filling out his time doing day labor on construction projects—demolition, painting, masonry—and ultimately earned a spot on a roofing crew in South Brooklyn, where he still works today. He used delivery work as a hedge when better-paying construction gigs slowed down, bouncing from pizzeria to pizzeria every couple of years.

There were good bosses and bad bosses, but the relationships in restaurants were, generally speaking, intimate and localized; even if takeout orders were nothing more than voices on the phone, restaurant owners knew their neighborhoods and knew their clientele. They sent you out on bicycles that belonged to them, and if you got hit by a car—a near inevitability for working cyclists in New York—you could usually expect them to help out with fees from the emergency room visit.

After Ajche had been in Bensonhurst for a few years, his wife followed him north, leaving their young children in the care of her sister in Guatemala City. Over time, the family rearranged itself around the fractured existence common to so many immigrants. To build a future that didn’t hinge on a bad tomato crop or the whims of the market for handicraft exports, both parents felt they had to leave. The kids grew up with their aunt in a house paid for with remittances, sharing milestones on a family group text. The advent of video chat has made things easier, but Ajche hasn’t been home since he first left. The last time he hugged his children, now 21 and 23, his daughter was a toddler; his son was still an infant.

Signs of a seismic shift in the takeout industry emerged in 2016 with the arrival of Uber Eats. In a sequence that’s become all too familiar in the era of tech platforms, the arrangement began as an especially generous one for workers and consumers alike, as apps competed to gain market share as fast as possible. There were sign-up and referral bonuses and favorable rates on deliveries.

As the apps lured more deliveristas and restaurant owners to their platforms, the calculus underlying the longstanding arrangements between restaurants and bicycle delivery workers began to fray. More and more, apps were where the customers were. As long as you could stomach the apps’ commissions, the appeal of hiring deliveristas on a per-order basis was self-evident: Rather than trying to anticipate a fickle market and absorb the costs of a worker’s entire shift on a slow night, the apps offered a bottomless pool of labor, perfectly calibrated to the demand. There were advantages for the workers too. New York had always been a place thick with potential employment for new arrivals who spoke little English or lacked immigration papers, but few jobs offered such flexibility and low barriers to entry. Buy a bike and a phone and you were on your way. If you needed the day off for child care or to go see about a better job somewhere else, you could take it without fear of reprisal.

In 2018 and 2019, as apps became enshrined as the dominant mode of delivery, e-bikes, not yet legal in New York, were becoming dominant in bike lanes. No urban cyclist is without sin, of course—tell me you’ve never coasted through a stop sign or crossed an intersection against the light—but delivery workers seemed to be especially cavalier, flying the wrong way down one-way streets, cruising at top speed with one hand and both eyes on a smartphone. A search on X (formerly Twitter) bears this out, with countless people complaining of “out of control” delivery workers. Riding with Ajche, though, I began to see how the deliveristas’ way of moving through the city was better viewed as a feature of the dynamics of their workplace, the pressure of the clock tempting them into ever riskier maneuvers. Scott Landers, whose consultancy, Figure 8, advises restaurants on delivery operations, refers to this as “machine learning doubling back on itself.” The apps collect data from thousands of routes a day and use that data to set parameters: “If the app learns that most drivers can do this in 10 minutes, then that becomes the expectation, and then there’s this arms race around the speed of the bicycle,” he says. Though he makes an effort to obey traffic laws most of the time, Ajche says it would be impossible for him to reprogram completely and ride without breaking the rules. “You’re battling time,” he says. “The apps keep sending you notifications. They pressure you, and the customer will say the food came late, and that’s how they block you.”

One afternoon last spring, I spoke with Juan Restrepo, the director of organizing for Transportation Alternatives, the leading advocacy group for pedestrians and cyclists in New York. We met at 14th Street and First Avenue, an intersection that Restrepo sees as emblematic of this kind of bike-on-pedestrian conflict. We crossed the street behind an older woman who was walking arm in arm with a friend just outside the crosswalk. Another foot to the right, it seemed, and she risked impalement on the handlebar of one of the e-bikes whizzing by.

Restrepo, in a black leather jacket, black jeans, black T-shirt, and black shoes, took up station on the little island of sidewalk between the bike lane and the rest of First Avenue, in line with a single row of parked cars. When the protected bike lane along First Avenue was built, he explained, it was touted as a model for the city, connecting Manhattan to the outer boroughs. But just a few years later it was bursting at the seams. “The infrastructure is not allowing people to safely get from point A to point B,” he said. The examples were almost too numerous to notice—cabs honking their way through the intersection to keep pedestrians from getting a jump on the walk sign; package carts and motor scooters sharing space with guys wearing headphones and riding with no hands.

New York’s transportation commissioner, Ydanis Rodriguez, has committed to making New York “the most walkable and bikeable city in the nation.” In April 2022, the city announced plans to spend $900 million by 2026 to support pedestrian and cyclist safety and make the transit improvements laid out in its new NYC Streets Plan. But Restrepo worries that City Hall lacks the political will to convert promises of funding into actual changes to the streetscape. “As a piece of legislation, it’s incredible, but then it becomes a question of ‘Where do those bike lanes go?’ or ‘Are the city council people supportive?’ Often the answer is ‘No’ or tepid,” he says. For example, in 2022, the first year of the plan, the city built just 20 miles of bike lanes, according to data from Transportation Alternatives. That was well short of the 50-mile benchmark required under the plan.

One example close to home for deliveristas is the proposed creation of a charging hub for e-bikes on a median along Broadway on the Upper West Side, an area where bike parking for delivery workers is notoriously difficult. Having safe charging stations has become an urgent need after a series of deadly fires occurred due to faulty lithium e-bike batteries being charged on residential electric circuits. But when the city proposed a charging hub at 72nd and Broadway, the local opposition was as unified as it was polite—at a public hearing, speaker after speaker acknowledged the contributions of delivery workers and the necessity of safer infrastructure, but they just didn’t want it there. Those plans are still moving forward, slowly, despite opposition from the local community board. Two other charging stations are in the works in the financial district and Williamsburg. But Ajche sees a more lasting solution in the possibility of an exchange program that would provide incentives to workers who turn over faulty batteries, along with regulation and enforcement to keep poorly made batteries from entering the market at all.

Two days after I joined Ajche for that rainy ride, we got back on the bike for one of his regular shifts in the financial district—some apps, to ensure that they can reliably meet demand, have begun allowing workers to sign up for set hours in particular neighborhoods, in exchange for predictable work and a fixed delivery perimeter. We spent three hours crisscrossing the financial district to the offices of white-shoe law firms and financiers—a small bag from Smoothie King, a personal pizza from a storefront below a Trump hotel, a poke bowl, and finally a sandwich, “add bacon,” which Ajche delivered to a sleek office tower on Greenwich Street, where Uber is the anchor tenant. Deliveristas weren’t allowed in, so we waited with a dozen others astride e-bikes laden with insulated food bags. A young man with a goatee and glasses came striding out in Allbirds and a V-neck tee. “Kevin?” Ajche asked. According to the receipt on the bag, the sandwich, with the delivery fee, came out to $27. What is the economic model that sustains this? I wondered.

Kevin, by all appearances, could have afforded a $35 sandwich just as easily as a $27 one, but how many Kevins were out there? Isn’t the whole point of having an office in Lower Manhattan that you can walk outside and grab your own sandwich within a couple of blocks? It seemed inescapable to me that this mode of delivery was a luxury service being consumed as an ordinary one, with deliveristas making up the difference in the form of erratic pay and onerous working conditions.

But Guallpa of the Worker’s Justice Project says deliveristas aren’t pushing for higher fees; they’re focused on a more equitable distribution of the platforms’ current profits. “Just look at how much revenue they’re creating,” she says. “We‘re talking about companies that are not making millions, they’re making billions.” The reported earnings of delivery apps tell a different story: DoorDash, for example, which has cornered more than 50 percent of the market in New York, reported a $1.37 billion loss in 2022, following the long startup tradition of losing money as the competition gets devoured. Perhaps much of that can be traced to creative accounting, lavish marketing campaigns, and exorbitant executive compensation; DoorDash CEO Tony Xu reportedly received a $413 million pay package in 2020. Still, it’s not clear that the model of food delivery at will is one that will pay for itself without some of the old guardrails—fixed hours and areas, minimum orders. As it stands, there’s evidence that many restaurants barely break even on deliveries that come through the apps.

To Ajche, one of the platforms’ central innovations has been to obscure the fundamentals of their business model, so that neither delivery workers nor restaurants have a clear understanding of how the algorithms are calculating their earnings. When I told Landers of Figure 8 about the $27 sandwich, he explained that restaurants that agree to pay higher commissions on each order get the bulk of the business, regardless of geography. In other words, there may have been a dozen other sandwich options closer to the customer, but they may not have seen them as an option in the app.

In the first week of June, as smoke from Canadian wildfires fouled the air in New York, Ajche was outside, as usual, delivering takeout to people who had the luxury of staying in their living rooms. For anyone paying attention, he tweeted out a selfie and a reminder: “We are essential workers,” he wrote. “We are working at all times regardless of the weather conditions, very hot, extreme cold, storms and this week poor air quality.” He ended with a raised first emoji.

Ajche is matter-of-fact about the sacrifices he’s made to give his children a shot at the kind of middle class life that didn’t seem possible for him and his wife in Guatemala. Without being able to spend time with them in the flesh, organizing fellow workers is one way to be a role model, to show them what he stands for. As hard as it’s been to live away from them, the strategy has worked out: His son is a law student with a job at a bank and his daughter is months from finishing psychology degree. Both had hoped to come visit New York in 2020, only to see their visa appointments canceled after the pandemic hit, only to be rescheduled for 2024. Until then, Ajche’s days will remain much the same: he’ll do roofing in the morning, and in the afternoons, he’ll get back on his bike.

You Might Also Like