Not wild about Harry: why fantasy fans have always had a problem with JK Rowling

In a 2005 Time magazine cover story, Harry Potter author JK Rowling set the cat among the muggles by stating that she didn’t consider herself a fantasy writer. The same article revealed that she hadn’t made it all the way through Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings – the ur-text for fantasy fans for decades – and that she had put down CS Lewis’s Narnia series before the end. She would never be forgiven.

“Fans send Rowling wands and quills by the bushel, but she admits, a bit shamefacedly, that she never actually uses them and that the wands go straight to her oldest daughter, Jessica,” goes the piece.

“The most popular living fantasy writer in the world doesn't even especially like fantasy novels. It wasn't until after [Harry Potter and Philosopher’s Stone] was published that it even occurred to her that she had written one.”

"That's the honest truth," she told Time. "You know, the unicorns were in there. There was the castle, God knows. But I really had not thought that that's what I was doing. And I think maybe the reason that it didn't occur to me is that I'm not a huge fan of fantasy."

In the world of mainstream literature, Rowling was, until about 10 minutes ago and her controversial tweets about trans people, beyond reproach. She shaped the childhoods of an entire generation, introducing millions of children to the delights of reading past bedtime. Moreover, with the character of Harry, she struck a blow on behalf of puny bespectacled 11 year-olds everywhere. Who could possibly object?

But not everyone has been drinking the butterbeer on Rowling. Within the fantasy genre Harry Potter is the ultimate divisive figure – adored by many, yes, but a source of resentment and frustration too. A few regard the author as nothing less than an infiltrator. There has, in particular, been disquiet concerning Potter’s place in the long-established literary tradition of the plucky boy wizard – and Rowling’s apparent reluctance to acknowledge his lineage.

Related to this is the fact that Rowling is a fantasy author who seems terribly sniffy about writing fantasy. Her brag in the Time piece, that she'd never finished Lord of the Rings, was a little like a vicar proudly announcing to his congregation that he isn’t much bothered with all that New Testament silliness. Instead of rings and wraiths she has name-dropped Roddy Doyle as her favourite author. (It should be noted that it is claimed elsewhere that she, in fact, read LotR as a teenager but that she didn’t finish Tolkien’s the Hobbit until after the Philosopher’s Stone.).

Rowling was especially critical of CS Lewis and his chaste take on fantasy (if Harry Potter is about growing up, Lewis was a celebration of keeping adulthood at bay). "There comes a point where Susan, who was the older girl, is lost to Narnia because she becomes interested in lipstick. She's become irreligious basically because she found sex," she told Time. "I have a big problem with that."

Her reticence is understandable, on one level. Until Game of Thrones, fantasy was the genre that dared not speak its name in respectable company. Among the literati, tut-tutting of Tolkien may well have have gained Rowling brownie points. It may have played well, too, with the trend-following grown-ups soon proudly reading Harry Potter on public transport.

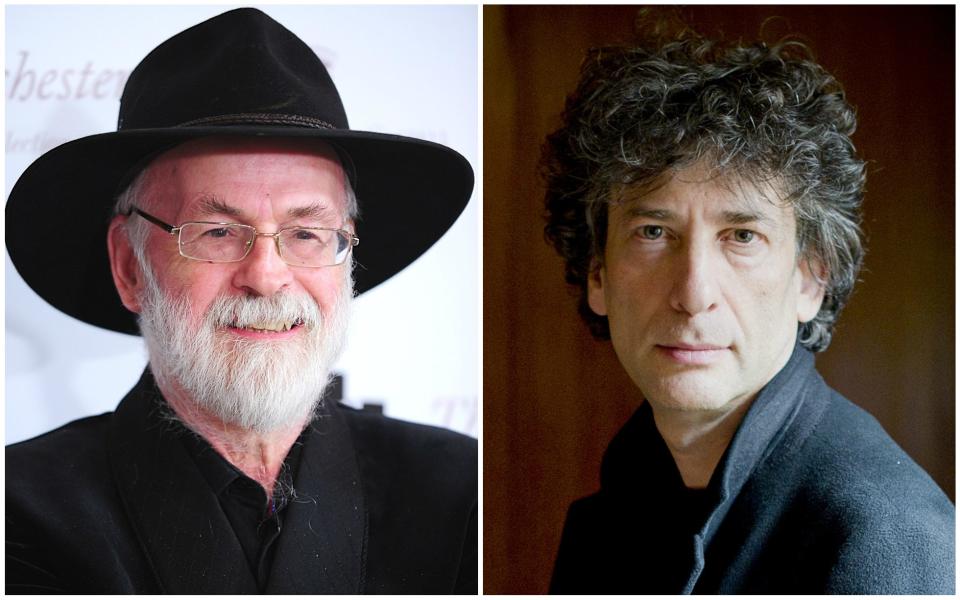

But her comments caused quite a stink in the fantasy community. Terry Pratchett, a master of the milieu in Britain, was among those to protest. “I would have thought that the wizards, witches, trolls, unicorns, hidden worlds, jumping chocolate frogs, owl mail, magic food, ghosts, broomsticks and spells would have given her a clue,” he said.

The other complaint against Harry Potter is that his adventures aren’t all that original. Fantasy writers have for decades been sending fledgling wizards off to magic schools, where they have endured all manner of scrapes and battled with nefarious foes. And yet in the wider world, Potter is acclaimed as a work of devastating originality.

This caused disgruntlement. Especially among writers whose boy wizard books predated Rowling and yet now stood accused of whooshing in on her coat-tails.

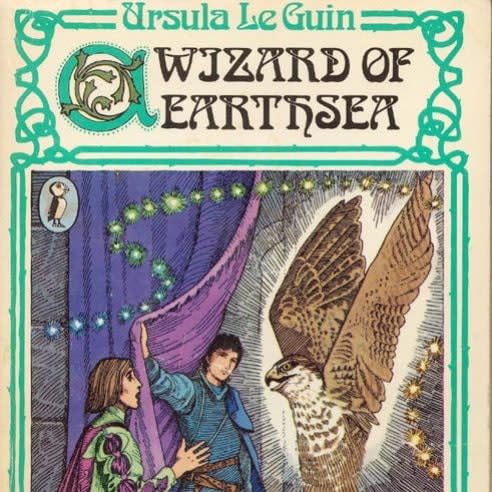

Among those baffled and a bit vexed by Potter-mania was Ursula Le Guin, a giant of 20th century fantasy. Decades before Harry went to Hogwarts she had dazzled young readers with a juvenile magician of her own in her 1968 classic A Wizard of Earthsea.

Earthsea and Potter have striking parallels. Each features a “chosen one” boy protagonist whose parents die when he is very young and who goes on to attend a school for wizards (Roke in the case of Earthsea, Hogwarts obviously for Potter). There, they gain a young rival and are recognised and resented as special in some way.

Le Guin shot down the idea that Rowling had borrowed from her. Rather, she said, both operated in an older tradition, with its roots in TH White’s the Once and Future King (1938).

Here, a young Arthur is apprenticed to a Dumbledore-ish “Merlyn” and the concept of a school for wizards is referenced in passing. Le Guin’s critique was that Rowling did not appear at all in a hurry to acknowledge the debt. Why was this?

“I didn’t originate the idea of a school for wizards — if anybody did it was TH White, though he did it in single throwaway line and didn’t develop it. I was the first to do that,” she said. “Years later, Rowling took the idea and developed it along other lines. She didn't plagiarise. She didn’t copy anything. Her book, in fact, could hardly be more different from mine, in style, spirit, everything.

“The only thing that rankles me is her apparent reluctance to admit that she ever learned anything from other writers. When ignorant critics praised her wonderful originality in inventing the idea of a wizards’ school, and some of them even seemed to believe that she had invented fantasy, she let them do so. This, I think, was ungenerous, and in the long run unwise."

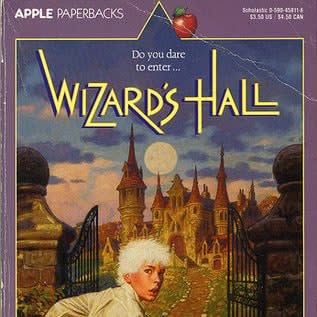

Another writer less than wild about Harry is Jane Yolen. Her 1991 children’s novel Wizard’s Hall concerns a young boy named Henry studying to be a magic user. “I read the first three [Harry Potter books]. The fourth one stopped me in my tracks, partially because even though the story moves along, I just don't feel like they're well written,” Yolen told Newsweek in 2005.

Yolen would later state that she didn’t feel Rowling was ripping her off. But both were drawing from the same literary well. “I’m pretty sure she never read my book,” Yolen told the Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy podcast in 2013.

“We were… using fantasy tropes — the wizard school, the pictures on the wall that move. I happen to have a hero whose name was Henry, not Harry. He also had a red-headed best friend and a girl who was also his best friend — though my girl was black, not white.

“And there was a wicked wizard who was trying to destroy the school, who was once a teacher at the school. But those are all fantasy tropes … There’s even a book that came out way before hers where children go off to a witch school or a wizard school by going on a mysterious train that no one else can see except the kids, at a major British train station — I don’t know if it was Victoria Station or King’s Cross. These things are out there … This is not new.”

Neil Gaiman, creator of Sandman and co-author with Terry Pratchett of Good Omens, is another dragged into the debate over where Rowling’s ideas came from. In his Books of Magic graphic novel, a forerunner to the Sandman series, a boy wizard is plucked from obscurity and charged with safeguarding humanity. As Harry Potter became a sensation people were quickly drawing parallels.

“My character Tim Hunter from Books of Magic who came out in 1990 was a small dark-haired boy with big round spectacles – a 12-year-old English boy – who has the potential to be the most powerful wizard in the world and has a little barn owl,” he acknowledged to January Magazine in 2001.

Yet he took issue with the suggestion that Rowling had used Books of Magic as a springboard. “All of the things that they actually have in common are such incredibly obvious, surface things that, had she actually been stealing, they were the things that would be first to be changed. Change hair colour from brown to fair, you lose the glasses, you know: that kind of thing.”

Time has not quelled the disquiet. As recently as last year, author Jill Murphy noted the parallels between her 1974 Worst Witch novel and Harry Potter in an interview with the Telegraph.

Both series feature young characters going to boarding school – Miss Cackle’s Academy for Witches in the case of the Worst Witch and its sequels. "You have to be gracious,” Murphy told the Telegraph.

Harry Potter isn’t even the first Harry Potter. In the 1986 comedy horror Troll, Noah Hathaway – aka Atreyu from Wolfgang Peterson’s NeverEnding Story – plays a character named Harry Potter Jr. And Troll’s plot, if not outright Potter-esque, is certainly vaguely familiar, with the young Harry apprenticed to a benevolent witch in a battle against a malevolent fairy creature. Troll director John Buechler took note and called his lawyer.

“In John's opinion, he created the first Harry Potter. JK Rowling says the idea just came to her,” Troll co-producer Peter Davy told the Hollywood News. “John was shocked when she came out with Harry Potter.” Buechler later sued for $20 million; a spokesperson for Rowling called the claims "ridiculous" and nothing came of the case.

Authors who have gone to court have been unsuccessful, as was the case with the estate of the late Adrian Jacobs which claimed Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire lifted from parts of his 1987 book, The Adventures of Willy the Wizard.

Fantasy, after all, has always been about recycling and referencing its own past. George RR Martin’s A Song Of Ice and Fire – adapted for television into Game of Thrones – is, for instance, an interrogation of Tolkien’s the Lord of the Rings. And Martin has accepted this, stating that, without Tolkien, he would never have become a fantasy writer.

Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials books meanwhile can be read as an impassioned argument against the mythological Christianity espoused by CS Lewis in his Narnia saga. The issue for fantasy fans is that Rowling has never acknowledged that she is part of such a tapestry. Indeed, by declaring her indifference to Tolkien and her love of Roddy Doyle she appears to place herself above it.

"It's true that we writers borrow words from each other,” said Orson Scott Card, whose Ender’s Game series tells of a young man from a troubled background chosen to lead the world against a hidden menace. “But we're supposed to admit it and not pretend we're original when we're not.”

Then there are those who decry what they regard as Rowling’s mishmash world-building. Before writing the Lord of the Rings, Tolkien spent decades creating elaborate languages for his fantastical races. Rowling, by contrast, chucks in elves, werewolves, flying broomsticks – a pick ’n mix of fantasy cliches.

“The setting is boring…” wrote one Rowling agnostic on the Reddit “Fantasy” forum. “Let's have an ordinary school, but magical! Let's have an ordinary British government, but magical! Let's include every single fantastic creature from every form of myth ever devised, plus the kitchen sink… How convenient and boring.”