‘We’re not the PC police!’: what sensitivity readers really do

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In 1860, Charles Dickens became friendly with a woman called Eliza Davis, whom he met while her husband was in the process of buying his house, and they became correspondents. Mrs Davis took the opportunity to complain about the anti-Semitic stereotypes Dickens had used in his depiction of Fagin in Oliver Twist three decades earlier.

In the original version of the book, the character is usually referred to as “The Jew” rather than simply “Fagin”; and when Dickens issued a uniform revised edition of his novels in 1867–8, he removed many instances of this epithet at Eliza Davis’s prompting. In other words, Mrs Davis was what we are now learning to call a “sensitivity reader” – somebody who scrutinises a manuscript for potentially offensive material.

This bit of literary history popped into my mind recently when the novelist John Boyne denounced the notion of sensitivity readers on Twitter: “On Sensitivity Readers: The best writers challenge, disturb, outrage. Imagine Gide, Miller, Dickens with an SR! No serious writer would ever allow their work to be so sanitised.”

Well, Dickens, at least, did. But Boyne’s hasty generalisation seems typical of the overheated rhetoric currently deployed in what has become something of a civil war in the Republic of Letters. Some authors sing the praises of those sensitivity readers who have divested their books of unintended offensive tropes. Others complain that thanks to sensitivity readers, freedom of literary expression is in more danger than at any time since the reforms of the 1960s, when the bans on books such as Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Last Exit to Brooklyn were finally thwarted; the difference between then and now, they add, is that the censors are not officious politicians but people whom publishers and writers actually pay to wield the red pen.

Among those who have been bruised by the experience of using sensitivity readers is Kate Clanchy, whose description gives you the impression of a body of people who make Orwell’s Ministry of Truth look easygoing. In a recent piece, she explained how sensitivity readers working on the revised version of her controversial memoir, Some Kids I Taught and What They Taught Me, found innumerable “offensive” terms. She was told, for example, that she “should not use ‘disfigure’ of a landscape… as presumably comparing bings – spoil heaps – to boils might be harmful to acne sufferers”.

But is the use of sensitivity readers really such a radical change in the publishing sphere? Writers have always sought advice on portraying cultures or groups with which they are not intimately familiar; the difference now is that this practice is becoming professionalised.

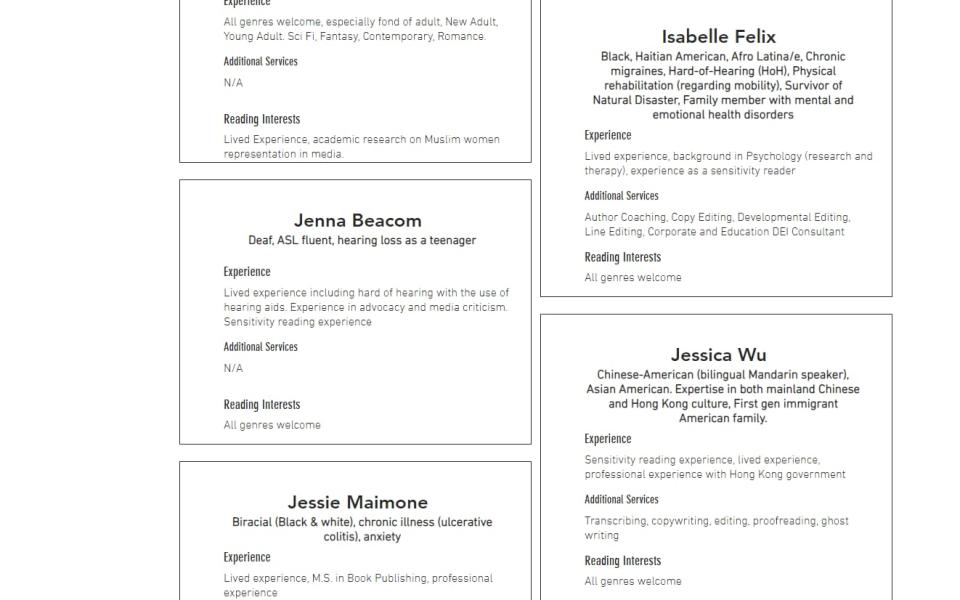

Many sensitivity readers are freelance, but others – especially in America, where they have been used much more widely and for longer than in Britain – work for large parent companies. Every reader has a profile in which they describe their background and specialist areas, and in many cases present a stark catalogue of experiences they have undergone and can provide comment on the reality of racism, homophobia, sexual assault, disability, alcoholism and more. According to the US Editorial Freelancers Association, the average fee for a sensitivity reader is $31–35 per hour, or $0.01–0.19 per word, which would work out at around $1,000–1,900 for the manuscript of a novel of average length (thus slightly cheaper than the average proofreading service).

Critics of the practice argue that, in sensitive times, sensitivity readers are being granted too much power over the content of books. It seems timely therefore to find out more about what sensitivity readers actually do: who they speak for, what they are trying to achieve, and how much power they really have.

Yasmin McClinton, a first-generation Ghanaian American, is a professional sensitivity (or authenticity) reader, as well as a freelance editor, former high-school teacher and (under the name Yasmin Angoe) novelist. Her involvement with sensitivity reading began “unintentionally”, she says, when she decided to train to be an editor and took part in a mentoring programme for people of colour who wanted to work in publishing; she was then offered a job by the company running the programme, which offers editorial services including sensitivity reading to writers and publishers.

What does a sensitivity review entail? “When I do a review, I’ll check for what the client specifically asks for. Most of the time, they ask for an overall view. They may ask me to read for African-American, black, immigrant or women’s experiences. They may ask me to read for areas based on my background as an educator – it depends. I’m looking for outdated, harmful, offensive terms – and phrases, stereotypes, appropriation, cherry-picking of elements of diversity that feel inauthentic and forced.”

I ask her if she has undertaken any training, and whether her job is to make note of what she personally feels is inauthentic or offensive, or to anticipate what others may be offended by. “As with any other job, there is continuous learning. I’m always curating resources I can use as a reference when I’m conducting reviews. If there is anything I’m not sure about, I’ll ask other editors that may be more knowledgeable. I attend webinars and whatever else I come across to ensure whatever I’m telling my clients is information based on research and fact.”

She adds: “Even if I read for areas listed as my ‘expertise’, I’m still only one person. It’s still only my viewpoint, and I let the clients know that. You can get 100 people to do a review, and it will only be 100 viewpoints. But even in the experiences that I don’t share, I consider areas in a manuscript that may cause readers outside of my personal experiences any concern. I leave a note letting the client know that I think this may be an issue. And if it’s something I’m not sure of, I suggest that they find a person from that particular group, to double-check.”

Dill Werner is a sensitivity reader as well as an author of young-adult fiction. Their specialities include “queer identities and sexuality, which includes being nonbinary, trans, and asexual. Additionally, I read for mental illness, trauma, disability, and overall ableist language. Because I’m Jewish and have a degree in German Language and Literature, I find myself reading quite a few books set in the Second World War.”

Werner “became an official sensitivity reader in 2018. Before then, I was part of the writing community, learning about publishing as I queried agents. I made friends with editors and authors along the way. Eventually, authors approached me, asking if I would read their manuscripts to make sure they accurately portrayed an aspect of my identity (for a fee, of course). Let’s say an author was writing a trans character, but they didn’t identify as trans themselves. They’d bring me on to make sure the representation was authentic and without issue. I soon discovered I loved the process.”

Now that Werner is an established professional, the process starts with the publisher sending them “a detailed note outlining which areas the sensitivity reader should include commentary on… I carefully read through the manuscript, making in-line notes as I come across certain words and situations. Once finished, I compose a letter to the author and editor, hitting on my key areas of concern and offering choices on how to amend any potential problems.

“As an example, let’s say I’m reading for ableist language and come across a sentence with the phrase ‘suffers from bipolar disorder.’ I’ll leave an in-line note saying: ‘Suffers from’ is an ableist and problematic phrase that can be harmful towards those living with mental illness. It’s preferable to say someone ‘lives with bipolar disorder’ or ‘has bipolar disorder’.

“Another term for sensitivity readers,” Werner adds, “is ‘authenticity reader’ or ‘diversity consultants’. Much of the time, I’m like a fact checker or content consultant. Maybe I need to make sure the Jewish characters aren’t falling victim to any anti-Semitic tropes. Perhaps these characters didn’t use the correct terms for ‘mom’ and ‘dad’ based on the time period and their specific Jewish community.”

Does Werner rely on their own instincts, or consult with other people? “I draw from my own experiences and understanding first. At the same time, there’s no way for me to know everything. I am by no means perfect!”

The concern some people have about sensitivity readers is that they’re forcing literature to become blander and safer. But, according to McClinton, that viewpoint is based on an exaggerated view of how powerful they are in the publishing industry.

“The concern I hear about [sensitivity] readers usually comes from authors who are concerned about their craft. And I think that fear of readers is ridiculous because sensitivity readers can’t tell anyone what not to do. It’s the publisher and the author who decide in the long run. A doctor can’t tell you to get a procedure done – they give you their assessment. They give you the risks if you don’t, but they can’t force you to say yes. Neither can a sensitivity reader.

“Sensitivity readers are not out there to kill creativity or dash anyone’s literary dreams. Write whatever it is you want to write. But be open to feedback and be open to the possibility that your work is an extension of you, and if you don’t want the readers to think you’re a racist or misogynist or whatever, then consider what you’re talking about. And above all, know your audience, and do your research.”

According to Werner, “the way we’re portrayed is laughable. I feel like the media makes sensitivity readers into the ‘PC police’! It’s become a joke in my household. Our negative portrayal then impacts how authors view sensitivity readers, like we want to tear their work to pieces or berate them for messing up in the slightest. I don’t know any sensitivity readers who have that kind of time and energy.

“My authors and their editors place an immense amount of trust in me. After all, they’re often allowing me access to their work before it’s finalised. Sometimes I read early drafts – personally I’d be anxious if I were in their position! Still, my authors and editors know I’ll never judge them for making mistakes. I’m here to help, not criticise.

“As a sensitivity reader, I merely have the power to make suggestions but never changes. That’s up to the editor and author. They have the final say in what goes and what stays… It’s never my intention to stifle the author or manipulate their voice. More than anything, I wish to stay true to their work and their vision.”

Many of the objections to sensitivity readers seem to come from people outside the publishing world, who haven’t realised how heavily books are edited in general and always have been. It has always been the editor’s call to decide what demographic a book’s likely readership will be from, and to prune it to that readership’s taste.

With commercial fiction, for instance, this may involve simplifying the plot or shortening the author’s sentences, or removing something that the editor worries will be seen as tasteless – one author I know tries to slip a scene that involves a man targeting moles in his garden with dynamite into every novel he writes, and his editor always removes it. It is not the case that before the advent of sensitivity readers, authors were allowed to simply write whatever they wanted without interference. Fears that literature will suddenly be stifled like never before seem somewhat exaggerated.

Sensitivity readers are, anyway, not compulsory in British publishing. Two editors I asked to comment for this article told me they had never used them – both were senior publishers who have been in the business for many decades.

My informative experience with sensitivity readers. https://t.co/kr7PeLi1ja

— Kate Clanchy (@KateClanchy1) February 17, 2022

One younger fiction editor, who asked not to be named, explained the circumstances in which she might commission a sensitivity reader. “Sometimes I think it’s necessary to have somebody check over a book that contains depictions of marginalised figures; or sometimes the author themselves will request it, and we will pay for it. I think it’s important that, say, white writers should be allowed to write about people of colour, and having a sensitivity reader helps with that process. It’s a way of preventing censorship.

“I would certainly never be influenced in terms of what I would publish – I would never send a manuscript I was considering publishing to a sensitivity reader and ask what they thought of it. That would be a complete abdication of responsibility.”

Many publishers ask more than one sensitivity reader to look at the same manuscript, a process that can be alarming to the author if, as in Kate Clanchy’s case, the same parts of the book are praised by one reader and criticised by another, and contradictory advice is received. But this is hardly an unusual state of affairs in publishing, says the editor I spoke to: “I’ve edited many historical novels, and often the author will ask three different historians about some historical detail, and come back with three contradictory opinions. What we do is work together, sift through the advice, and work out what will serve the book best.”

It may be the case, of course, that some panicky publishers, disproportionately frightened of having their books pulled apart on social media, may uncritically adopt each and every suggestion made by their sensitivity readers, or at least be less confident in exercising their own judgement. If they are not robust enough to stand up to the tricateuses of Twitter, however, it’s probably preferable in the end that the white, middle-class publishing establishment use sensitivity readers rather than trying to second-guess themselves what people might find offensive.

What may be more likely to happen is that publishers try to deflect criticism of offensive aspects of their books by pointing to the fact that they have gone through the sensitivity reading process.

Sensitivity readers are vulnerable to exploitation, as the writer Justina Ireland explained in 2018 when she closed down the Sensitivity Readers Database she had set up two years earlier. “I have spoken to numerous sensitivity eeaders who have shared stories of being ignored, not paid, or just treated abominably. I have seen authors, when criticised for their depictions within their books, point to sensitivity readers as a magical shield against critical analysis…

“This was never the point of sensitivity readers, and the more I see this process abused by people already undertaking to tell the stories of others, the less I have been able to promote sensitivity reading as a boon to marginalised people.”

McClinton has not had trouble of this kind with publishers, but has experienced occasional difficulties with authors: “I've had pushback and an aggressive attempt to justify why those flagged items are in the manuscript. Then I know it’s lip-service and they’re not serious about making sure their work isn’t grossly offensive.

“That’s when I remind them that ultimately the work is theirs and they can decide to take or leave my advice. I’m just one person. They can check with another reader if they want. But they should also be ready for whatever comes should they keep the content in and are called out on it later. And they shouldn’t say they ‘had a reader’ as if that person gave them the okay, because there are always receipts.”

The editor to whom I spoke insists that sensitivity readers are not simply an insurance policy against possible criticism. “If you read the acknowledgements in, say, a history book, the author may thank several other historians who read the manuscript, but will ultimately say ‘all mistakes are my own responsibility’. That’s our attitude to sensitivity readers. Content of the book is the responsibility of the author and the editor.”

Of course, the use of sensitivity readers may be no less subject to the law of unintended consequences than anything else – and I have outlined some potential problems in a previous article. But speaking as somebody who has argued in favour of the right to offend – to the extent of saying that even Jimmy Carr’s fouler jokes should not be censored – I don’t see anything wrong in principle with authors being able to make use of people who can alert them to instances of unintentional offence.

It’s also natural enough that some people will see this close scrutiny of books for offensive language, tropes and stereotypes as being over-the-top. No doubt people thought the same about Eliza Davis, godmother of sensitivity readers, when she complained about the careless stereotyping and dehumanising of the Jewish Fagin in Oliver Twist. It was an attitude harder to hold, though, for those who lived to see the dehumanising of Jews reach its logical conclusion in the 1930s and 1940s.