No Signal

It’s impossible to say whether the death of Wyoming splitboarder Trace Carrillo in an avalanche in April of 2020 was due to a beacon malfunction, but it’s clear that before that incident, snow safety product manufacturer Pieps and its North American distributor Black Diamond were already aware of a potentially fatal issue with its line of beacons and hadn’t yet taken public action to address the issue.

Another, earlier accident involving a Pieps beacon dominated the conversation in 2020. Professional skier Nick McNutt’s Pieps beacon turned off when he was caught in an avalanche in March. A firestorm erupted on social media and eventually led to the company’s announcement of a product recall, six months after the issue started drawing widespread attention. That wasn’t the end of the story, however–others are still seeking recourse for a faulty product that may have cost lives.

One person who was impacted, Trace Carrillo’s father, only learned about the product recall this year. Concerned his son’s death in 2020 may have been caused in part by beacon failure, he sought a wrongful death lawsuit against Pieps and Black Diamond. The case was dismissed in August of 2023 when the judge ruled that the two-year statute of limitations had passed, thanks to a technicality in Wyoming law that determines when that period starts.

Photo provided by Tracey Carrillo

The Avalanche

On Wednesday, April 1, 2020, Trace Carrillo and Anna Meteyer, both residents of Jackson, WY, set out to ski in the backcountry off Highway 22, on Teton Pass.

It was a strange time. Most people weren’t yet using the now-familiar shorthand of “Covid” or “the pandemic” to describe the state of the world. Without a good understanding of how the virus spread, mountain communities like Jackson were policing themselves strictly, telling tourists to stay away and warning restless skiers not to fill up parking lots. All the ski hills in the area had closed abruptly, as had Grand Teton National Park, so the convenient backcountry access points on Teton Pass were seeing even more skier traffic than usual.

Ethan Lobdell, who has been a volunteer on the Teton County Search & Rescue team for over thirteen years, drew a parallel between Covid and recreating in the backcountry. “There were so many unknowns we were trying to make sense of,” he remembered. “There is a degree of uncertainty and a managing of personal risk that exists with both, and Covid really put those concepts in people’s faces.”

Starting at around 11 am, Carrillo and Meteyer skinned north from the busy Coal Creek trailhead to ski one of the southernmost peaks of the Teton Range, Taylor, a hulking 10,300-foot mountain with cliff-studded southeast- and east-facing flanks and large slide paths that run its entire prominence before converging in steep terrain traps. The Bridger Teton Avalanche Center rated the avalanche hazard as moderate that day, with the potential for wind slabs at high elevations and unstable snow in steep terrain.

Carrillo, 28, was an experienced splitboarder from New Mexico. He had graduated with a degree in natural resource recreation and management at the University of Utah, taught avalanche courses at his college, and interned at the Utah Avalanche Center in Salt Lake City before working as a wilderness ranger with the US Forest Service in Wyoming. His friends and family described him as a capable and joyful adventurer.

Meteyer was less experienced; as a relatively new backcountry rider, she had gotten up to speed the way so many Jackson transplants do, by riding outside the gates at Jackson Hole Mountain Resort as often as possible. It was her first time on Taylor Mountain, and throughout the tour she deferred to Carrillo as the more knowledgeable rider.

Meteyer, speaking over a year later on the podcast The Fine Line, a series produced by Teton County Search & Rescue, remembered that neither of them proposed doing a beacon check before they started their tour, although the thought did occur to her. In her interview, she expressed the self-recrimination, frustration, and grief that she has experienced since that day, as well as the progress she has made toward forgiving herself.

After summiting on the graybird afternoon, the pair decided on one of the more conservative descents off the peak, because they were concerned that the snow seemed slabby and had warmed more than expected as they climbed.

Meteyer dropped one of the initial pitches first and turned with her phone out to capture a video of Carrillo riding the slope. As she hit record, she saw the snow move under his board and heard the unmistakable, stomach-dropping whumph of a slab breaking above him. Because she was in the line of fire, she hastily snowboarded a short distance to safety before stopping to reassess the situation.

A period of stress and chaos followed. Meteyer had lost sight of her partner, but she called out to Carrillo and thought she might have heard an answer, so she wasn’t sure if he had been buried in the slide or not. The pair didn’t have radios; “God do I wish I’d had one,” she said.

She switched her beacon to search and started to wallow back uphill through deep snow and avalanche debris, leaving her backpack behind. She called her movements haphazard and said she didn’t travel as efficiently as she would have liked.

“We don’t always get to be the superhero we think we should be,” she reflected in the podcast interview.

The idea of her friend being buried was “so extremely overwhelming” that Meteyer pushed the thought out of her brain, saying that if she had allowed that fear to creep in, she would have shut down. She felt confused and alone, pulled in multiple directions by uncertainty, and overcome by the gravity of the situation. And her beacon wasn’t picking up a signal.

After a long search, Meteyer, at a loss for what to do, descended into the Coal Creek drainage and called 911 when she had cell service. TCSAR and other regional agencies responded and searched the slide debris into the evening before leaving the scene due to increasing avalanche hazard.

Photo: TCSAR

“It was really cold, getting dark, and we were searching at the base of the southeast face, underneath two pretty darn large avy paths,” SAR team member Lobdell recalled during an interview with Powder in October of this year. “We assumed one had slid but we were not sure the status of the other. So we were cold, in the bottom of a gully, probing desperately for a body. There is a bizarre confluence of all these different emotions that intersect in these experiences, a kodachrome of emotions between rescuers that might be in sync or might be going off in all different directions.”

The next morning, after avalanche mitigation was performed by helicopter, handlers from Jackson Hole Ski Patrol brought avalanche search dogs to the scene. Once they reached the toe of the slide, it only took a few minutes for a dog to hit on Carrillo’s scent; his body was found two feet under the snow, not far from where Meteyer had searched with her beacon.

Carrillo’s Pieps DSP Sport beacon was turned off.

According to the coroner’s report, there were no signs of massive trauma; asphyxiation was the cause of death. This means that there was a good chance that Carrillo would have lived if he had been found within the first fifteen to twenty minutes of burial, what experts call the “survival phase.”

Photo: TCSAR

Distressing Days

The community’s anguish was compounded when, only two days later, just over the state line in Idaho and less than twenty miles from Taylor Mountain, another avalanche fatality occurred. Rob Kincaid was a beloved professional snowmobiler from Victor, ID, and a vocal proponent of motorized snow safety. He was caught in an avalanche in the Austin Canyon drainage as he and his group headed back to the trailhead after a long day of riding.

Kincaid was carrying an Ortovox beacon that appeared to have been off at the time of his burial, even though his riding partner of many years, David McClure, said that Kincaid was always the one instigating preseason beacon search parties and promoting motorized-specific avalanche education.

The gut punch of two experienced backcountry users dying within days of each other, and neither having beacons that were transmitting when they were buried, shook the Teton region.

This all transpired under the unique cloud of uncertainty and unease brought about by the pandemic. The Teton County SAR team members couldn’t carpool to trailheads or debrief together afterward in their hangar as they normally would. They not only had to monitor themselves for signs of stress after a traumatic incident like a fatal burial, but also for signs of a new, headline-making illness. They felt like they couldn’t even comfort Meteyer with a hug, even though she was devastated following the avalanche.

“We as a team really felt it, that Covid was a compounding factor,” Lobdell said. “The factors start to stack up, and the capacity an individual has to be healthy and take care of themselves through isolation and the persistent stress of a pandemic, and then to add a very traumatic rescue situation, can be compromised.”

Despite the lack of physical touch, Meteyer said that the love and support of the TCSAR team helped her feel like she wouldn’t be rejected or judged for the incident. “They gave me hope that I might be met with empathy and compassion by my community.”

TCSAR kept Carrillo’s father Tracey updated with frequent phone calls during the search, and eventually had to give him the heartbreaking news that his son’s body had been located. The family flew from Texas to Wyoming, and Tracey was immediately struck by the kindness of the Jackson community; the pastor of a local church picked him and his wife up at the airport late at night and congregants lined the road in their cars to welcome the Carrillos into town. Covid restrictions prevented them from having a proper funeral, but after the cremation, Tracey was taken to see the mountain that had claimed his son’s life, and when the Carrillos checked in for their flight home with Trace’s remains, TSA agents at the Jackson Hole Airport stood at attention as they passed through security.

Calling for Action

Later in the same year, there was something of a reckoning for the European snow safety brand Pieps and Black Diamond, the company that distributes Pieps products in North America.

In October of 2020, professional skier Nick McNutt revealed that he had been buried in an avalanche in Pemberton, British Columbia, in March of that year while filming for the Teton Gravity Research ski movie Make Believe. Professional guide Christina Lustenberger chimed in on Instagram, describing the nightmare of watching McNutt trigger a large overhanging pillow while skiing his line. The train of snow overtook him and dragged him through trees. Thanks to Lustenberger’s guide training and TGR’s rigorous snow safety program for athletes and filmers, she and the crew of pro skiers and cinematographers flew into action, confident that they could extricate him quickly.

But, to their horror, their beacons never picked up a signal.

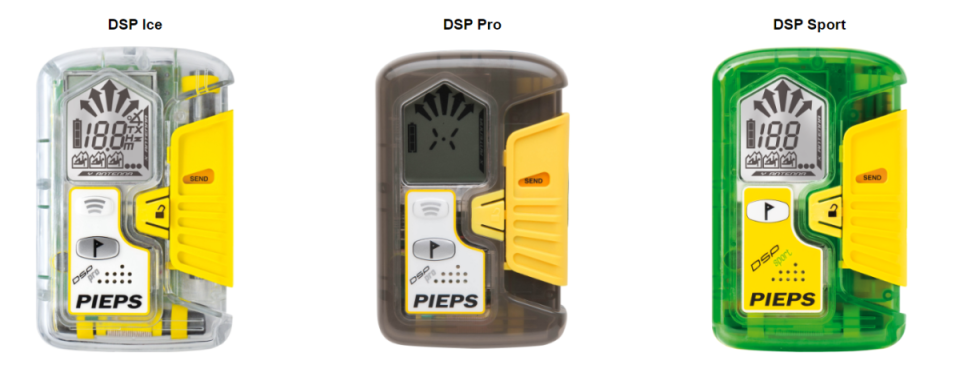

The group resorted to a probe line and fortunately found McNutt after five agonizing minutes, but Lustenberger described the sinking sensation of having to use a fallback search method when their primary search tool failed them. After extricating McNutt from the snow and performing a full body check, they determined that his Pieps DSP Pro, worn in a harness on his chest, was turned off. They knew they had performed a beacon check earlier in the day, and McNutt’s beacon should have been transmitting.

They privately alerted Pieps and Black Diamond in March after the incident, but when it seemed after several months that the companies weren’t going to take action, they took the issue to social media, inspiring hundreds of commenters to call for product recalls and brand boycotts.

McNutt’s revelation echoed and elevated the voice of Brianne Howard, the widow of Corey Lynam, a Canadian skier who died in an avalanche in March of 2017 under similar circumstances. Lynam, an experienced and meticulous backcountry skier, was buried and his Pieps DSP Sport transceiver appeared to have switched modes during the avalanche, leaving his partners unable to locate him. It took dozens of people and dogs hours to find his body.

Howard heard reports from other skiers that pointed to a consistent point of failure in Pieps beacons. Since 2017, she had been trying to warn consumers and Pieps about the product’s potential design flaw, but said she had been rebuffed by the company. When McNutt and Lustenberger started the conversation online, it brought attention back to the circumstances of Lynam’s death.

In response to the online firestorm in October of 2020, Pieps maintained that it had done its due diligence in ensuring the devices were functional, and posted a statement on Instagram saying that the beacons have “undergone vigorous testing and exceed all certification standards.” The statement, which hasn’t been removed from the company’s Instagram page, says that “a beacon is a personal safety tool which must be properly used and maintained. Any misuse may compromise its functionality.”

It was only at the end of the following North American ski season, in April of 2021, that Black Diamond and Pieps announced a voluntary product recall, after receiving 63 reports of devices that switched modes unexpectedly while in use. In the recall, the company recommended that owners of the Pieps DSP Pro, DSP Pro Ice, and DSP Sport “immediately stop using” the product, and offered owners a free hard case that was supposed to mitigate the issue of the mode button accidentally sliding from send to search or turning off. There was no offer of a refund or free repair of faulty beacons.

Image courtesy of Pieps

Many think that Black Diamond and Pieps didn’t go far enough in addressing the apparent flaw in its product.

“At first I was glad that steps were seemingly being taken to correct the issue, but they had allowed another entire winter season to go by first before informing the public of the known problems, which I thought was incredibly irresponsible,” McNutt wrote in an email to Powder last month. “It also became clear that they were only interested in doing the bare minimum by offering a voluntary recall of just the carrying harness and not the device itself.”

The leadership team at Black Diamond declined to be interviewed or to provide comment for this article.

Wrongful Death

After the avalanche on Taylor, no one in Trace Carrillo’s immediate circle publicly discussed the relationship between his beacon and his death. One of his backcountry partners, who asked to remain anonymous due to his position in the ski industry, said that Carrillo’s friends made the conscious decision not to tell his parents about the Pieps issue, to spare them the additional pain. In 2021, when Anna Meteyer narrated the incident on The Fine Line, the brand of beacon that Carrillo was carrying was never mentioned in the podcast.

It wasn’t until nearly three years after Carrillo’s death that his father, Tracey, learned about the Pieps product recall. Early in 2023, an investigator with the Consumer Product Safety Commission called Tracey because the commission had learned of Trace’s death and wanted to know if he had been using a Pieps beacon. The investigator couldn’t share too much information with Tracey but did give him a few keywords to Google.

That was the first Tracey had heard of the recall.

“The deeper I dug, the more I found about it,” he told Powder. “It spurred us to pursue some type of litigation. Trace was top in his field–he knew the terrain, knew his equipment. We can’t say for certain that he had his beacon turned on, but in talking to his friends, he was always the one to do the beacon check, even if he didn’t that day.”

The Carrillos turned over Trace’s Pieps beacon to the Consumer Product Safety Commission so that the agency could test the unit to determine if it was defective; as of early December, the CPSC’s Division of Field Operations was still in the midst of its investigation.

Tracey contacted a firm in Minnesota that had posted online about the recall and was offering case evaluations. No one at that firm was licensed to practice law in Wyoming where the fatality had occurred, but they directed him to Rice Harbut Elliott Law, a Canadian firm in Vancouver, BC, that was working on a class action lawsuit against Black Diamond, Pieps, and their parent company, Clarus Corporation.

That set the process in motion. In March, Nikolas Sulley, an attorney with Fuicelli & Lee in Colorado, received a call from a Canadian attorney who was working on RHE’s class action lawsuit and was attempting to bring the case stateside but needed an American plaintiff.

Sulley is licensed in Wyoming and was interested in representing the Carrillo family in a wrongful death lawsuit. Based on his research he believed that the statute of limitations window was rapidly closing, so he hustled to assemble the necessary documents and got the complaint filed only days before what he perceived as the deadline. The complaint alleges that the defendants, Black Diamond, Pieps, and Clarus, were responsible for Trace Carrillo’s death due to “negligence and strict products liability.”

In its response to the complaint, Black Diamond and its co-defendants denied all allegations of liability. The defendants said that the fatality was “caused or contributed to by the negligence, carelessness, inattention, or otherwise wrongful or unsafe acts of decedent or other persons,” and argued that the complaint was untimely based on Wyoming law.

In the late 1990s the Wyoming Supreme Court had issued what Sulley described as an “unfortunate opinion” stating that the two-year statute of limitations (or, more technically, the condition precedent) for wrongful death begins at the time of death, not when the cause of death is determined. Although the complaint came within two years of the Pieps product recall, it was filed just over three years after Trace’s death; under Wyoming law, the clock had run out on a wrongful death lawsuit.

In August, the U.S. District Court for the District of Wyoming issued an opinion that was in line with the Wyoming Supreme Court: the discovery rule, which states that the statute of limitations on bringing a claim does not begin to run until the claimant discovers an injury or loss, does not apply to wrongful death. Sulley noted with bitter irony that if Trace had survived the avalanche, he would have had four years following the incident to bring negligence and product liability claims, but as he had perished, there was only a two-year window for recourse.

Sulley admitted that the outcome was somewhat expected, but he had hoped to get lucky.

The Wyoming District Court also awarded the defense costs and fees to Tracey; the total was already considerable, and if he appealed the decision and lost, he would be responsible for even more of the defense’s fees and costs.

“Considering the Wyoming District Court’s opinion, the Carrillos understandably didn’t want to take that risk,” Sulley said. Instead, Tracey waived his right to appeal the decision in exchange for not having to pay the defense’s fees and costs.

“I can’t imagine the pain they experienced,” Sulley said. “To have that wound reopened, to learn after three years that Trace’s death may have been caused by someone else rather than a mistake.”

He emphasized that the Carrillo family was not litigious or looking for money, they were simply looking for closure. “Six months into our discussions about the case, they had never asked about money, about what they could get out of this,” he said. Instead, they were focused on making sure that no backcountry travelers were still relying on a recalled safety product.

“There’s no telling how many people out there still aren’t aware they’re using a defective beacon,” Tracey added.

While Sulley thinks there still may be an opportunity to hold Black Diamond accountable for the product defect through a class action, a wrongful death suit is no longer an option, since the statute of limitations has passed in every appropriate state.

"With an outcome like this, you really feel as though justice didn't prevail," he said.

The civil case in Canada is still pending; the class certification hearing, in which the judge will rule on whether the case hits the threshold for a class action lawsuit, is now scheduled for May of 2024. The plaintiff’s civil claim alleges that the class members would not have purchased a Pieps transceiver if they had known of the defect in the product, so they are owed damages for the cost of the transceiver as well as any beacons purchased to replace a Pieps model.

Sulley believes that Black Diamond had ample opportunity in 2017 and again in 2020 to investigate the claims that the Pieps beacons weren’t reliable.

“The sole intent of the product is to keep people safe. They continued to sell those products until November of 2020, and continued to profit for over three years on a product they knew could potentially be defective,” Sulley said. “In my opinion the recall was not a recall, it was a free piece of plastic to protect your device. It was not an admission of a defective product.”

Sulley is skeptical that much has changed at the company, because since the 2021 recall, there have been two more beacon recalls for different issues.

In another product recall in July of 2022, Black Diamond warned that a slew of beacons (Pieps Pro BT, Powder BT, Micro BT Button, Micro BT Sensor, Micro BT Race, and the Black Diamond-branded Recon BT and Guide BT, as well as the previously-recalled DSP line), might fail to switch from “send” to “search,” which presents a different but still concerning scenario in the backcountry. The company did offer free repair or replacements of beacons that exhibited the issue, but again did not promise a refund.

Black Diamond announced yet another voluntary recall in March of 2023 on the Black Diamond Recon LT, warning that the model required a firmware patch. Since it was not a physical design flaw, a user could update his or her beacon at home, but Black Diamond also offered a free service update or full refund on the Recon LT.

Pieps is not the only manufacturer to recall its snow safety products in the US; within the last five years, Ortovox and BCA have both announced beacon recalls on certain models. In those instances, however, there were no incidents reported as a result of the defective products.

Pieps still sells the Pro BT and the Powder BT; according to its website, after the 2022 recall of those models, the company performed an internal investigation and identified that the root cause of the failure to search problem was a “material handling/assembly anomaly in manufacturing.” Pieps claimed to have pulled and tested every unit before returning it to the inventory.

In October of this year, Pieps released what it is calling “the new benchmark,” the Pro IPS, which promises reduced interference in transmit mode and “unprecedented signal stability.” The Pro IPS will not be available in North America until 2024.

In Memory

There can be an enormous cost to mistakes in winter backcountry travel and equipment, but tragedy sometimes leads to change.

Nick McNutt said that his close call in 2020 changed how he practices backcountry safety. “We have started to incorporate more training surrounding strategic probe line work and practicing scenarios where a transceiver is either not transmitting or was never worn,” McNutt said. “Aside from that, I personally won’t go out with someone who has [a recalled Pieps device] and I know I’m not alone in that decision.”

Every year, TGR hosts the International Pro Rider Workshop for its athletes, providing training in snow safety, first aid, and rescue protocol. When McNutt was caught in the avalanche, his backcountry partners proved the value of being proficient in rescue scenarios.

“The IPRW program has been immensely helpful–there’s something even more beneficial to practice all of these rescue scenarios with the same people I often visit the backcountry with,” he said. “On top of that, we start to see where our own personal weaknesses lie and where the strengths of our other crew members can shine, whether that be first aid, leadership, communication, or locating victims.”

After Idaho snowmobiler Rob Kincaid’s avalanche death, his riding partner David McClure worked with a local trails advocacy group and the US Forest Service to erect three electronic beacon checkpoints at popular motorized trailheads in the area. McClure, along with Kincaid’s son Riley, who followed in his father’s path and is now a professional on the hill-climbing circuit, put out a short film early this season on the importance of backcountry education.

Photo: Julia Tellman

Teton County SAR communications director Matt Hansen said that the deaths of Carrillo and Kincaid within days of each other led the organization to increase its emphasis on beacon checks. TCSAR introduced a new tagline in the winter of 2020-21: “Check yourself. Check your friends. Every single time.” The motto reminds users that taking shortcuts in the backcountry can have dire consequences.

“After those two fatalities, we really made a strong effort to spread that message to our entire community,” Hansen said. “Make sure your beacon is fully functional and perform a beacon check, every single time, no matter what. You just never know.”

“Plus it has the benefit of focusing your mindset,” he added. “Taking a couple seconds or a minute to pause and perform this task with your partners is a good reminder that this is serious. And then you can go enjoy your ski tour.”

In early 2021, at the foot of Taylor Mountain in the Coal Creek drainage, the Teton Backcountry Alliance installed a beacon park where users can hone their search skills and practice responding to multiple burials. Snow safety professionals are united in the belief that frequent, realistic companion rescue practice is an essential part of progressing as a backcountry user.

“The number of variables and factors at play in the backcountry is far greater than we can manage intellectually, so we have to establish rituals and practice behaviors to reduce that cognitive load and simplify decision-making,” TCSAR team member Ethan Lobdell said.

Photo provided by Tracey Carrillo

After his death, Trace Carrillo’s friends and family raised $25,000 in order to set up an endowed scholarship at the University of Utah, where he received his undergraduate degree and then taught in the outdoor recreation program. Through the fund, at least two students every winter can take one of the school’s snow safety courses for free. This year’s scholarship recipients will be notified on December 15.

Carrillo’s father Tracey said that the scholarship was a symbolic way for Trace, who had cared so much about people getting an education in the backcountry, to continue serving as a mentor in the community. “It’s his legacy that we wanted to carry on.”