Your No-Panic Guide to Handling Summer Emergencies Like a Pro

THE BEST multitool for any outdoor outing is common sense. But sometimes what seems like the smartest move in a summer safety emergency can be a painful or deadly mistake. Take the MH Ultimate Survival Quiz to spot your fails and fix them before they happen, so you’ll ace any unexpected emergency pressure test.

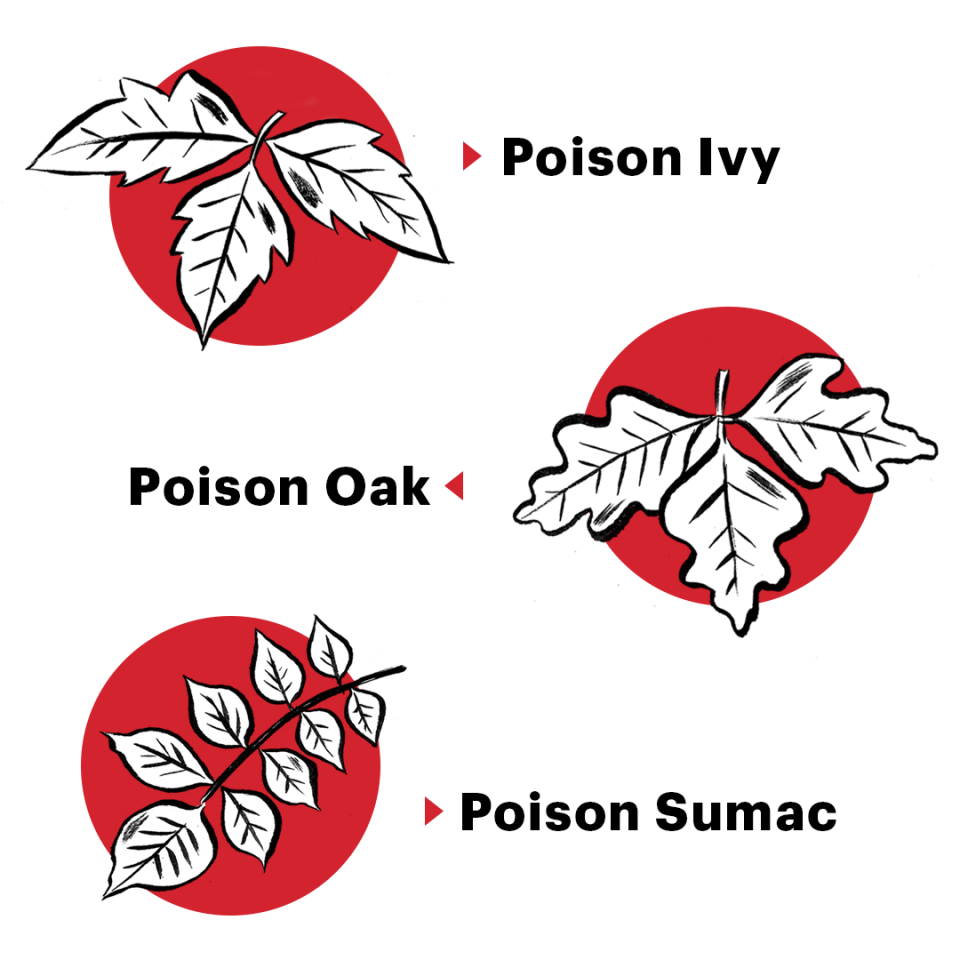

1.) You’ve been stomping around poison ivy, oak, or sumac on your summer hike. The best way to prevent a rash is to:

Rinse your skin with rubbing alcohol.

Scrub the area with a mix of one part bleach, one part water.

Wash your skin with soap and water.

ANSWER: 1 OR 3

ALL THREE of these plants contain a sticky, invisible oil called urushiol. Getting it off within 30 minutes of exposure will prevent the oil from chemically bonding with your skin, lessening the itchy, oozy misery. Don’t overthink cleanup and turn to bleach: That shouldn’t be used on skin. Soap and water do the trick, as long as the soap contains a degreasing agent, as in dishwashing liquid. Rubbing alcohol can also remove urushiol, so carry alcohol wipes when camping or hiking if you can’t wash immediately. With either remedy, rinse your skin thoroughly and avoid scrubbing, as this can irritate the skin.

Know Your Dangerous Leaves

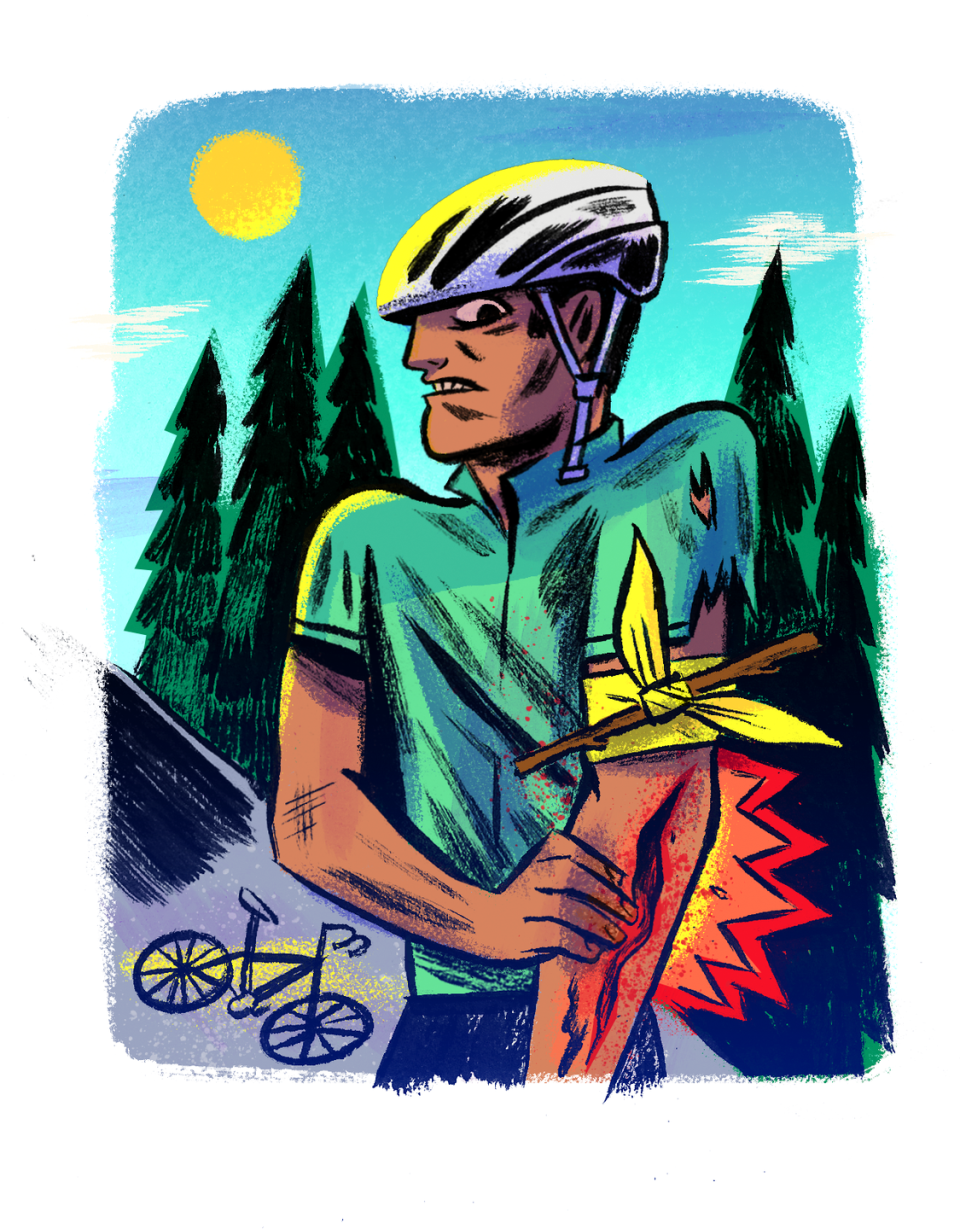

2.) Your friend fell, and now his arm or leg is spurting blood. To make a tourniquet, you should grab which of the following?

A thin wrap, like an electrical cord, shoelace, or guitar string.

A wider wrap—a sturdy strip of fabric, like a ratchet strap, or even a rash guard or a long sleeve from a shirt.

ANSWER: 2

DESPITE WHAT you might have seen in action films, any rope that makes your muscles pop out more isn’t actually helpful in this emergency. If your tourniquet is less than an inch and a half wide, it will dig into the skin, cause mind-bending pain, and not stop the bleeding. If there’s no lever or windlass to wind it tight, it won’t work, either.

Use these tips to make a tourniquet like a pro:

• Apply the wrap a few inches above the wound, but never on a joint.

• Tie half of the knot; place a sturdy straight object, such as a stick, across it; then finish the knot. This is your windlass.

• Use the windlass to screw the tourniquet down tight enough to stop the bleeding, like the valve on a spigot. It will still hurt like hell, but don't ease up on the pressure until the victim reaches professional medical help.

3.) You’re in the middle of a hike or trail run and develop a nickel-sized—or bigger—blister on your foot. You should:

Pop it, then bandage it up.

Leave it be, tighten your shoes, and carry on.

Lubricate the spot with lotion or petroleum jelly to keep the friction down.

ANSWER: 1

FRICTION FROM a rubbing shoe is what creates a painful, annoying, and infection-prone blister. Slathering the spot with lotion or petroleum jelly won’t help—it rubs off and leaves the area moist and ripe for worse blisters. Prevent pain and trouble by puncturing the blister gently around the periphery to drain the liquid, leaving the blister’s “roof” intact. Bandage it to avoid further rubbing—even duct tape can do in a pinch.

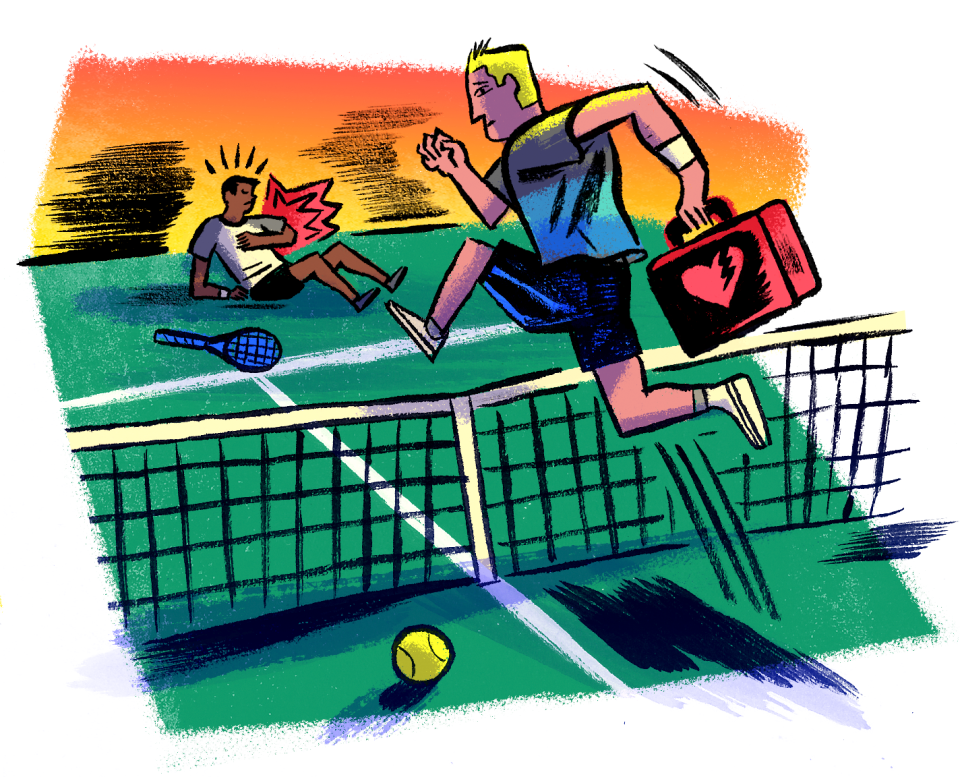

4.) Your friend has severe chest pain and collapses on the tennis court. The first thing you should do is find and hook them up to a nearby AED.

True

False

ANSWER: 2

AEDs (automated external defibrillators) are all over public spaces these days. These remarkable little computers—marked with the letters AED—deliver a powerful electric shock to the heart. Some are mounted on the wall in a suitcase-like container; others are built into walls behind glass doors. But grabbing one isn’t the first thing you should do in this emergency situation. Instead, confirm that the person is unconscious and unresponsive by shouting at and shaking them. Next, call 911 and check for breathing and a pulse.

If you can’t find a pulse, operate the AED using this process:

• Grab and prepare the AED; place the pads as directed by the machine.

• From there, an AED does most of the rest for you. Power it up and follow the instructions or voice prompts. Then stay clear of the victim once the AED cycle starts, especially if they’re wet. The device first checks the heart’s activity and then delivers its jolts accordingly. If no jolt is needed, it won’t deliver one but may tell you to administer CPR.

5.) If you don’t have an AED, or the AED didn’t rouse the person, how long should you perform CPR on someone who’s unconscious?

Until an emergency responder arrives.

Until the situation becomes too unsafe to continue.

Answer 1 or 2.

Ten minutes. After that, there’s no use.

ANSWER: 3

DON'T EVER stop CPR because you think it’s hopeless, says Pauline Meekins, M.D., an emergency-room physician in Chico, California. “I had one woman in her 20s come in,” she says. “She was blue. ‘Dead.’ I worked on her for 31 minutes and she eventually left the hospital just fine.” What that means for you: “No layperson should ever stop CPR. Not unless you’re in a fire, on a sinking boat, or EMS gets there.”

If you haven’t had formal CPR training, at least do this hands-only version (after calling 911), recommended by the American Heart Association. CPR can double or even triple a person’s chance of survival:

• Place the heel of one hand in the center of the chest. Place the other on top of it and interlace your fingers.

• Keeping your arms straight, push down hard and fast.

• Aim for about 100 to 120 compressions a minute, or as fast as the beat in “Stayin’ Alive.”

6.) You make a bad cast and impale a friend with your barbed fishhook. To remove it, you should:

Apologize for the new piercing, then push until the tip comes out of the skin, snip off the barb, and back it out.

Leave it in until you can see a doctor.

Apply pressure downward and forward to release the barb, tie a string to the base of the J, and pull it out.

Just yank it out backward.

ANSWER: 3

REMEMBER THAT a barb is designed to keep the hook in a violently shaking fish; it’s not supposed to slide out easily. Just yanking it backward will do a ton of damage. The string method counters that; pressing down ensures that the barb won’t grab more skin on the way back out. If the hook is all the way through, option A works, but the apology better be great. See a doc if it’s in a tricky spot, like an eye or tendon.

7.) A thunderstorm pops up while you’re hiking or camping. You should:

Shelter under a tree.

Stand at the edge of a hiking shelter or beneath a cliff.

Lie flat in an open area, praying that the storm will pass.

None of the above.

ANSWER: 4

LIGHTNING IS attracted to the tallest objects, so your instinct to just take emergency cover can go wrong fast. If you’re under a shelter or cliff, move way back to reduce the chance of a strike channeling through you. The best move: Stay in the open, keep your feet together, and crouch down, wrapping your arms around your knees. Keep your head low to minimize your target area. (If you have a foam pad, stand on top of it.) If there’s time, double back to the car, as long as it has a hard top. It’s one of the safest temporary shelters around.

8.) If you find yourself being pulled out to sea in a rip current, you should:

Swim as hard as you can to try to get back to shore.

Flip on your back and float until the current lessens.

Swim parallel to the shore until the current peters out.

Answers 2 and 3

ANSWER: 4

YOUR INSTINCT may be to sprint for shore. But swimming against the current will only exhaust you. Instead, try to swim parallel to shore, and be aware that the current might carry you out a bit. If you get tired, you can back-float to save energy. Eventually you’ll reach calmer water further out and be able to look back at where the waves are breaking—that’s where you want to go. Chart your path of least resistance to shore (which might be a diagonal, not a straight line).

9.) The first thing you should do to tame a jellyfish sting is:

Swear like hell while flushing it with vinegar.

Swear like hell, then pee on it.

Rub sand, baking soda, or meat tenderizer on the site.

Douse it with cold water.

ANSWER: 1 (SWEARING OPTIONAL)

A JELLYFISH sting doesn’t just hurt; it keeps radiating. If you get stung in the water this summer, rinsing the area with the first available liquid will likely make things worse: Water discharges unreleased microscopic stinging capsules (there are plenty), and urine isn’t acidic enough to deactivate them. Other folk remedies are bunk, with the exception of one: Research has found that vinegar can deactivate the stinging cells (nematocysts) of nearly every kind of jellyfish. Then immerse the wound in hot water (110° to 115°F, a little hotter than a shower) for 45 minutes.

10.) SHAAAARK! You’re approached or bumped in the water by a shark. Which of these things should you NOT do?

Yell loudly.

Punch it in the nose, claw its gills, and gouge its eyes.

Churn wildly to scare it away.

Swim away.

ANSWER: 3

MAKING A scene might give some land-based predators pause, but in the water it’s sign language for “wounded animal,” which means easy prey, also known as “lunch.” If you spot a shark nearby, first try to swim smoothly and steadily away. If it engages, it may be time to try targeting all the sensitive areas (B). Yelling isn’t a proven way to scare sharks, but when a great white reportedly latched onto New Zealand surfer Nick Minogue’s surfboard and arm earlier this year, he punched the animal in the eye and yelled, “Fuck off!” And. It. Did.

You Might Also Like