No One Knows Who Started the Stonewall Rebellion, but These Leaders Were Key

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

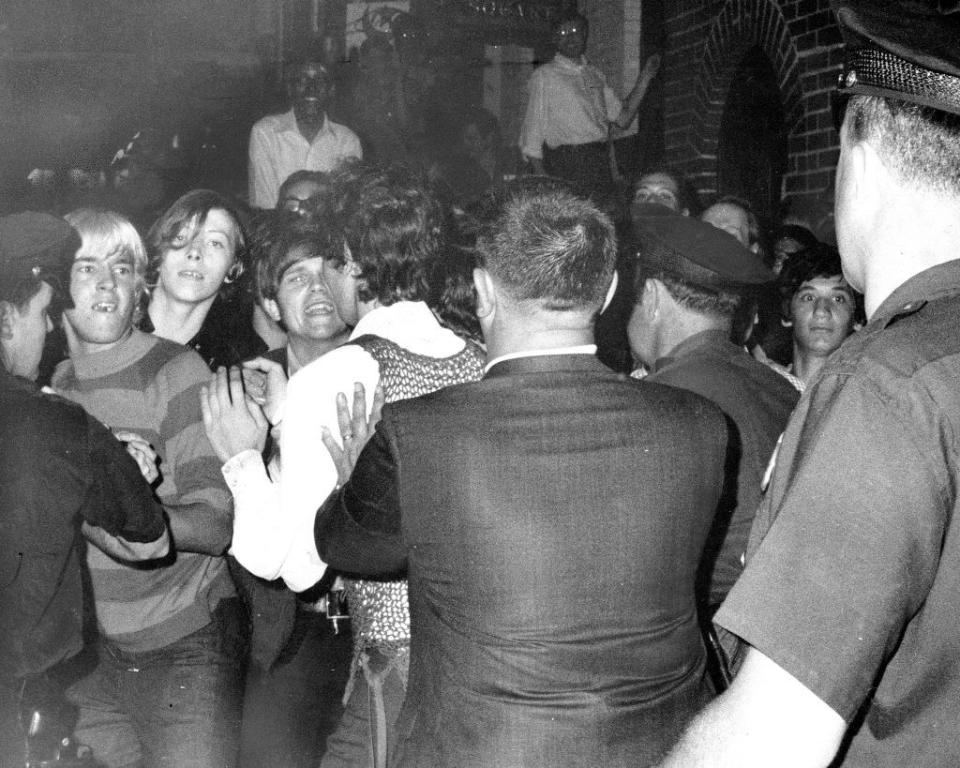

There has been much discussion and writing about "who threw the first brick or punch at Stonewall?" It's a question reflecting the many different accounts of the June 28, 1969 protests.

In the '60s, gay bars were frequently raided by police, in large part because it was both illegal to sell alcohol to gay people and to dress in drag. The Stonewall Inn, located in NYC's Greenwich Village, had been a popular spot for queer New Yorkers, and so there was a large crowd of LGBTQ+ people gathered outside the bar following the June 28 raid. While there is no consensus on who initiated the response, bar-goers, tired of being discriminated against, began to fight back against the police. It started specifically with trans women and homeless youths resisting arrest. The conflict escalated until the original officers found themselves barricaded inside of Stonewall, which led the crowd to throw bottles and other objects into the bar—though we don't know who initiated the rebellion. (Per the Library of Congress, those who were at Stonewall that night describe the event as an "uprising or rebellion," explaining that "riot" was the term preferred by police "to justify their use of force.")

This gave way to several days of confrontations and demonstrations that were instrumental in birthing the modern LGBTQ+ activist movement. Leaders like Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, Stormé DeLarverie, and Miss Major Griffin-Gracy—young New York residents at the time—are all referenced as participants in the Stonewall uprising, but their lives and lifetime of work in the LGBTQ+ community deserve their own celebration.

DeLarverie is believed by some to have been the first person to throw a punch at the bar, according to Lisa Cannistraci in The New York Times. However, again, the details are based on disparate tellings, and according to Michael Bronski—Harvard professor and author of A Queer History of the United States for Young People—that detail isn't pivotal.

"People want their history like it’s Betsy Ross, it’s George Washington, it’s Abraham Lincoln," Bronski tells Oprah Daily. "They want a person. In the case of Stonewall, that’s simply not the case."

While there is no way to know every name that was crucial to Stonewall and the movement for LGBTQ+ rights that it ignited, here are some important leaders and storylines to familiarize yourself with ahead of Pride Month.

Stonewall led directly to the founding of the Gay Liberation Front.

Prior to the Stonewall rebellion, besides the Society for Human Rights, the Mattachine Society, and the Daughters of Bilitis, there were relatively few LGBTQ+ advocacy groups. One of the biggest ways the impact of Stonewall was felt was that more organizations advocating for gay rights were started.

“Stonewall happens in June of ‘69, Gay Liberation Front New York begins by the middle or end of July, and quickly there’s a Gay Liberation Front in Michigan, a Gay Liberation Front in San Francisco," Bronski says. "By September, or by fall semester, there were about 350 Gay Liberation Fronts across the country on college campuses. Something clearly clicked and it was just the time for this to happen."

In an interview with NPR, Karla Jay, who helped run the Gay Liberation Front, said that the early pride parades were inspired by the 1969 uprising. "We set out to create a march on the first anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. And if we hadn't done that, nobody would remember Stonewall today," she said.

Brenda Howard, who was connected to many people that attended the initial Stonewall demonstrations, was key in planning a one-month anniversary rally for Stonewall in July 1969, per Them. She was later involved in organizing other New York celebrations like Gay Pride Week and Christopher Street Liberation Day, and is known by many as "The Mother of Pride."

Marsha P. Johnson was a key leader in New York’s LGBTQ+ community.

Originally from Elizabeth, NJ, Johnson moved to New York in the mid-1960s and quickly became an important part of the city's drag community, while earning money as a sex worker. According to the Marsha P. Johnson Memorial, she was known to some as a "drag mother" because of her penchant for helping youths and unhoused people in need, as well as "The Saint of Christopher Street."

Following her (still unexplained) death in 1992, her name become synonymous with the fight for LGBTQ+ rights for Black people. Today, there's a Marsha P. Johnson Institute which focuses on arts and community organizing for trans people of color.

Johnson and Sylvia Rivera founded the mutual aid organization STAR.

In the wake of Stonewall, Johnson and Rivera worked together to create Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), which offered aid to transgender sex workers, as well as LGBTQ+ youth in New York. Both women were survivors of abuse and exploitation, and sought to make life safer and better for those in similar positions.

STAR was founded in November 1970, initially inspired by a protest at New York University. Per the New York Historical Society, Rivera served as the group's president, while Johnson assumed the role of vice president.

Rivera, a trans Latina woman, was close friends with Johnson. The pair met in New York in 1963, and both became fixtures of the city's LGBTQ+ community and drag scene. Rivera, a lifelong New Yorker, passed away in 2002, after consistently fighting for the inclusion of trans people in the burgeoning gay rights movement.

Bubbles Rose Lee, another instrumental early member of STAR, was also crucial in opening STAR House, which reportedly housed around 20 people, until its closure in July 1971.

"We had a STAR House—a place for all of us to sleep. It was only four rooms, and the landlord had turned the electricity off. So we lived there by candlelight, a floating bunch of 15 to 25 queens, cramped in those rooms with all our wardrobe. But it worked," Rivera once said, according to the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project.

The impact of STAR and STAR House has been felt in the forming of other mutual aid and housing organizations that specifically aim to assist queer youth. Transy House, which Rusty Mae Moore and Chelsea Goodwin ran from 1995 to 2008, was inspired by STAR House and offered safe housing to people who would otherwise have been unhoused.

It was actually the last place that Sylvia Rivera lived—she was there from 1997 until she passed in 2002. New York City is planning to unveil monuments to Rivera and Johnson sometime in 2021, which would be the city's first permanent statues honoring trans women.

The Sylvia Rivera Law Project is an organization that continues her mission by working with trans, gender nonconforming, and intersex people who are marginalized, specifically focusing on immigrants, those who are imprisoned, and those lacking access to essential services.

Many of the important Stonewall leaders were involved in other social causes, too.

Per Bronski, it's crucial to talk about Stonewall in tandem with other social movements that were blooming in the '60s and '70s, as none of these struggles existed in isolation.

"I think it’s impossible to look at Stonewall without thinking about the large numbers of African American street demonstrations from the Black Panthers and the Black Power organizations, including six years of essentially urban uprisings every summer," says Bronski. "I think it’s impossible to see Stonewall without thinking about the massive amount of anti-war demonstrations that were going on and without thinking about the women’s liberation marches that were happening."

Rivera spoke about being involved in the Civil Rights movement prior to Stonewall, according to the National Women's History Museum.

"Before gay rights, before the Stonewall, I was involved in the Black Liberation movement, the peace movement...I felt I had the time and I knew that I had to do something. My revolutionary blood was going back then. I was involved with that," she said.

Johnson championed trans people of color, and was also involved in HIV/AIDS advocacy through organizations like ACT UP.

Miss Major Griffin-Gracy helped run the Transgender Gender-Variant Intersex Justice Project in San Francisco and has been an activist for over 40 years.

Miss Major has spoken about her experience of being a woman in a men's prison—she served time at Attica State Prison—and has worked to stop the abuse of trans people and non-conforming people in the American carceral system.

One notable role held by Miss Major was as the first executive director of Transgender Gender-Variant and Intersex Justice Project, a nonprofit focused on the mistreatment many in those groups face while in prisons and detention centers. They provide leadership training programs and help with reentry following time served, as well as legal advice.

Miss Major also executive produced the documentary Trans in Trumpland, a series that focuses on how four trans people in America dealt with anti-trans legislation and sentiment in places like Idaho, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Texas.

She was also the subject of her own documentary: 2015's aptly titled MAJOR! which explored her life and legacy of activism.

Stormé DeLarverie was a drag icon who performed with the Jewel Box Revue.

Beyond perhaps having "thrown the first punch," DeLarverie is also considered to have been a hugely important drag performer, as a member of the Jewel Box Revue, which GQ calls "the period's only racially integrated drag troupe."

She specifically served as the group's M.C., and was the only performer who dressed as a man, with the rest performing as women. According to GQ, DeLarverie was also a style icon in New York City circles, known for wearing distinct suits around the city. She was once photographed by the legendary Diane Arbus.

Many others who were present at Stonewall went on to make significant contributions to the LGBTQ+ community, its push for acceptance and recognition, and its vast impact on culture around the globe.

You Might Also Like