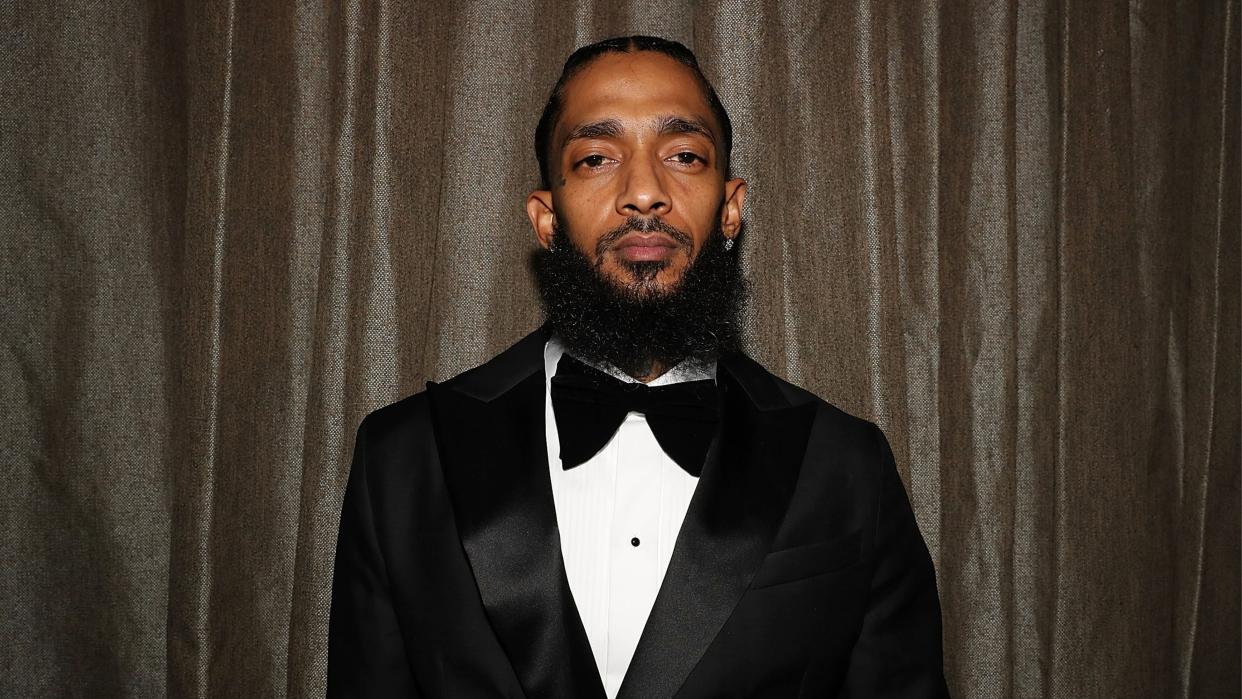

Nipsey Hussle's Death Brings a New Generation of Hip-Hop Heartbreak

In this op-ed, writer Jamilah King unpacks Nipsey Hussle's death, the legacy he leaves behind, and the history of heartbreak in hip-hop.

It wasn’t supposed to end like this. But too often in hip-hop, it does.

In late February, rapper Nipsey Hussle and actress Lauren London were introduced to mainstream pop culture as an industry power couple, in GQ. The theme was that their lives, and their love, were a fairytale. There was Nipsey, standing a statuesque 6-foot-3, in an all-white Louis Vuitton outfit with a white horse that carried the petite London, dressed in matching all-white, hair flowing down her shoulders. That they were standing in the middle of Slauson Avenue, one of South Central Los Angeles's main thoroughfares, brought home for fans what made their love and their art resonate with so many—Nipsey was a neighborhood kid who had made it out, and Lauren loved him for it.

Their fairy-tale romance was aspirational, but it was also relatable. Their lives were not about the glitz and glamour of Hollywood, but instead their love story was one that ordinary black Angelenos could relate to: late-night trips to taco trucks, afternoons at strip malls, weekends at cookouts, and sudden and irrational cravings for bean pie. And they made art for black people: London starred in the cult classic ATL and BET's The Game, as well as in They both achieved professional success on their own terms, without forgetting or abandoning the communities that made them.

In the aftermath of Nipsey’s sudden and brutal murder, on March 31 — right in the heart of the neighborhood he loved so fiercely — hip-hop is in a state of mourning. Even for fans who didn’t closely follow his music or intimately know the streets he claimed, news of his death hit especially hard. And the reason his death was felt so deeply, particularly if you’re young, black, and consider yourself part of hip-hop, is because his story is frighteningly familiar.

Nispey’s death represents the type of senseless violence that stole a generation of hip-hop’s brightest stars. Now that violence, which once seemed to be a thing of the past, is back. And it’s introducing a new generation of fans to the enduring legacy of heartbreak in hip-hop — a distinctly black art form that will always be anchored in the punishing realities of black life in America.

Nipsey’s death matters because every black life has worth. But he took pains to live exceptionally. He was born and raised in South Central and at 14 became a member of the notorious Rolling ’60s Neighborhood Crips, one of the biggest street gangs in Los Angeles. After years of selling CDs from the trunk of his car, he reached a level of underground success. In 2013, he began selling limited-edition physical copies of his independently released mixtape, Crenshaw, for $100 apiece, which caught the attention of Jay-Z, who bought 100 copies. (As fate would have it, another fan who tried desperately to get copies of the hard-to-find mixtape was London, who bought a bulk of albums as gifts for her colleagues on The Game and struck up a romance with Nipsey soon afterward.)

Success bred opportunity: Nipsey opened a coworking space called Vector 90 to bring a tech incubator to South Central. He partnered with a Fatburger and a barbershop, and he restored a beloved neighborhood roller rink. The day after he was killed, he was even slated to meet with members of the Los Angeles Police Department to help develop a community-response plan to gang violence. When asked during a 2018 interview on Power 105.1 FM’s Breakfast Club why he featured stories about gang life so prominently in his music, Nipsey made it clear that his primary audience was his community.

“I wanted what I had to say to impact individuals like myself, young people that was in these areas that was controlled by gang banging,” he said. “I wanted to be able to say, ‘I’m one of you, and wherever I end up, you gone know that you could end up there, too. Whether it’s at the top of the game as a business owner, I came from this. I’m not on the outside of this culture.’”

Like Nipsey, I’m a California kid who grew up on the unfulfilled promise of hood prophets like Tupac Shakur. I was in middle school when 2Pac was killed, and I remember the single “To Live and Die in LA” being released months after his murder and becoming a sort of macabre theme song for what it meant to be young and black in America. Less than a year later, Biggie Smalls was shot to death in Los Angeles, which only seemed to underscore that point even further. If ‘Pac and Biggie, two 20-something millionaires at the top of their game, could be gunned down, it could literally happen to anyone.

And it did. What made both deaths so extraordinary was that they weren’t actually extraordinary at all. In black communities across the country, murder rates throughout the 1980s and early 1990s skyrocketed, driven largely by gang disputes that were themselves underwritten by the crack cocaine crisis and decades of economic and political disinvestment. The ’90s were an era of moral panicking about sagging jeans and so-called “super-predators,” and the music of that decade was often a reflection of the anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder that plagued scores of young black people who carried the burden of trying to survive in such environments.

But in recent years, the themes of have hip-hop changed. Hip-hop, a black and brown art form, reached global success, allowing for a variety of subgenres and types of representations beyond the themes of gangs and inner-city violence. And for a while, some American cities — often full of poor and working-class black people creating their own communities — changed, too, as violent-crime rates in many places dropped to all-time lows.

But recently, murder rates have started to increase, often in these same black communities, and once again hip-hop can’t escape the fatalities. In Brooklyn, there’s been a 64 percent increase in homicides in the first few months of 2019, according to The New York Times. One of the killings that has garnered the most attention is that of 15-year-old Samuel Joseph, who was shot at point-blank range in his building’s lobby. In the Miami area, 20-year-old XXXTentacion was shot and killed in June 2018.

And then there’s Nipsey Hussle, whose murder was one of 11 that rocked Los Angeles in a single week. What makes his death so hard to stomach is that it seemed so avoidable. Nipsey had committed himself to telling stories of L.A.’s street life, but he always stopped short of glorifying it. For nearly the entirety of his career, he made a name for himself in hip-hop’s “underground,” eschewing big labels and licensing deals, opting instead to maintain control of all of his work. And he was reaping the rewards only recently, with his first major-label release of 2018’s Victory Lap, for which he was nominated for a Grammy.

That's not say his legacy isn't complicated: he has often been criticized for homophobia and conspiracy theories, and his music didn’t shy away from references to his gang affiliations and the violence those entailed.

But his image was also awash in representations of love, its own softness, hazy like an L.A. sunset. In a video for GQ on how well people know their partners, he bragged about getting a top score when answering London's questions about nicknames and favorite colors: He got 24 out of 30 right.

And then there's Instagram, where the rapper chronicled a life of glitz, occasional glamour, and snapshots of down-to-earth rootedness. There were the trips to Eritrea, his paternal homeland, with his father and brother, and Nipsey talking with his 90-year-old grandmother. There were the selfies of incarcerated loved ones, and the accompanying comments from neighborhood friends who hadn’t seen them in years and wished them well. And moments with his 7-year-old daughter, Emani, whom he called by her nickname, “Mani Mom,” and with his 2-year-old son, whom he called “Kross the Boss.” And then, of course, there was the fairy tale.

In hip-hop, fairy tales don’t last. The culture is representative of the people who make it, who are themselves reflections of the grinding realities of black life in America. People are imperfect, and, when they’re black, they often die too soon. They leave work behind, and families, too. The violent masculinity that defined a generation of hip-hop never left the music, but for a while, it could abide sitting off in a corner.

Now it is once again elbowing its way to center stage, demanding that we see it in all of its complex glory. It has no patience for fairy tales.

Let us slide into your DMs. Sign up for the Teen Vogue daily email.

Want more from Teen Vogue? Check this out: Lauryn Hill Taught Me About Being Black in a Mis-Educated America