Nick Offerman’s Enchanting Journey into the Mountains of Japan

This article originally appeared on Outside

We carried the enormous, sacred rice cake up the stone steps of the trail to the Shinto shrine and, exhaling and squatting, placed it gingerly upon the modest, low wooden altar, me doing my best not to slip a disk. There my friend Mike and I left the XXL-pizza-size offering to... well, the elements, I guess? To whatever birds and critters populate a Japanese mountain? I tried to ask our host, the priest Kumagai-san, what would now happen to this massive flapjack, but he simply smiled and nodded, then directed us to ring the substantial, ancient brass bell hanging from the top of the shrine.

This required use of a log suspended from a pair of ropes hanging next to the bell. After winning a wordless session of You first; no, you first, I insist with Mike, I grabbed a third rope dangling from the center of the log and prepared to execute a full-body, two-handed swing to make the bell go bong. The elderly Shinto priest, correctly assessing the amount of adolescence still coursing through my 19-year-old body, gave me a grim smile and said, "One time," lest I turn this reverential ceremony into a cacophony that would shatter every Sapporo bottle within a mile. But believe me when I tell you that your corn-fed correspondent rang that goddamn bell with enough gusto to vibrate your innards.

This wasn't the first ritual bell ringing of my life, given that I'd been an altar boy at St. Mary's in Minooka, Illinois. If only we'd had the wherewithal to hold church in the woods, like these Japanese folks did! Our Catholic masses were so sleep inducing that the only highlight was the multi-tinkle clanging of a behandled cluster of four altar bells, which sounded like Santa's sleigh advancing for a few seconds in stop-and-go traffic. We desperate young lads scrambled to become altar boys just so we'd have the chance to bestow that one remotely interesting moment on the congregation.

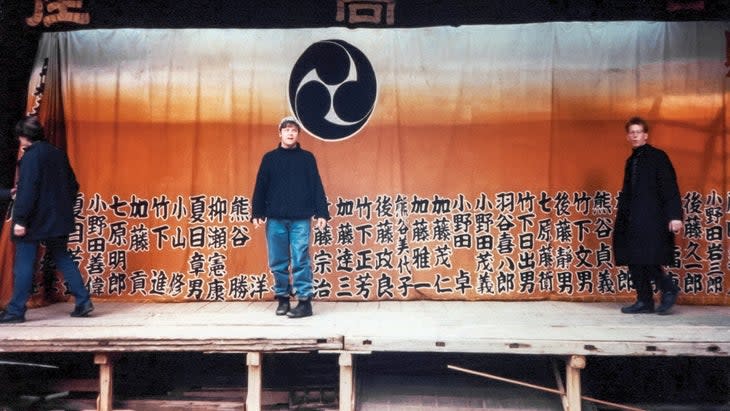

Slamming a log into a giant, patinated bell on a mountainside was a whole different order of experience and part of a life-altering opportunity for me, though not the kind you might expect. I wasn't on a retreat to learn about Shinto and Buddhism. Mike and I were traveling as performers in a Kabuki-theater show that had been created by our sensei Shozo Sato at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The year was 1991, and about 20 of us prancing Illini theater students were putting on an adaptation of The Iliad called Achilles: A Kabuki Play. Our tour included a handful of venues, from the bright lights of Tokyo to the tiny mountain village of Damine, where we were housed with local families for the few days we were there to participate in the town's 300-year-old Kabuki festival. Mike and I got bunked at the priest's house, most likely because he asked for a couple donkey-like actors who could carry 30 pounds of rice cake up a mountain.

Once the massive bell tone had faded from the countryside, we were directed by Kumagai-san to the head of a well-worn trail leading into the forest. He gestured right this way, as if to say, "You ring the bell, then you take the walk." Like any other American kids from the 1980s would have, we saw in him the mysteriously charming sensibility of Mr. Miyagi from The Karate Kid. Without waiting for further instructions, we pressed our right fists to our open left palms, nodded respectfully, and said, "Hai." Then we set off into the trees.

The light transitioned instantly from bright day to shadow, and the sounds of the world were cut off by the lush insulation of Japanese oak, beech, birch, and maple, along with healthy stands of conifers. Mike wandered ahead to afford us both some solitude. The air was so clean and sweet, and the birds and flora were just foreign enough, that I felt like I had ducked through a magic wardrobe into an enchanted landscape. Every so often, I would notice a small white cloth ribbon tied in a conspicuous spot--on the twiggy branch of a gnarled old tree, around a sapling in a small copse of pines, on a moss-kissed rock, or near a particularly pastoral viewpoint along a stream the trail ran beside. Our sensei would later explain that the ribbons signified special features of nature identified as part of a god.

Winding my way uphill, I came to a rocky outcrop with a stream gushing and burbling down it. I don't know why we humans love to see water succumb to gravity, but damn if we don't go apeshit about it. I stood there and stared, rapt, for several minutes--at the innumerable points of light and ever morphing, dancing cataracts and pooling rivulets--as the tumbling waters sang the sweetest of songs. My eyes darted here and there as I attempted to catch every tiny delight on offer, but of course I had no chance of succeeding. Instead I let out a deep breath and allowed the sights, sounds, and scents of this holy place to wash over me. Ahhhh.

The benevolent massage to my senses lulled me into solace, the moment steeped in reverence for the realization that I could never fully comprehend all the information in just this one small part of nature. Letting go of the need to know everything felt right to me in a pretty deep way, like a first tiny step toward the adult knowledge we all aspire to. I was stone-cold epiphanized. I would later come to learn that this feeling of dumping the concerns from my head is exactly what Japanese tea gardens are designed to accomplish: to prepare the initiate to receive the wisdom of the ceremony with an open, unfettered mind.

Which meant I was perfectly set up for what was to come when we got to Damine.

According to legend, this high-altitude village ran into trouble hundreds of years ago when a woodsman accidentally chopped down one of the shogun's trees. Word spread that the shogun, a powerful and deadly feudal warlord, was coming to investigate, and the villagers began to pray that they might be spared his wrath. A solemn promise was made that they would perform Kabuki every year to honor and thank Guanyin, the goddess of mercy, if she would only intervene.

Lo, the village was struck by an impossibly rare June blizzard, canceling the shogun's flights (I assume?). The village was saved from punishment, and the people kept their promise, holding an annual festival celebrating Kabuki ever since. Our Illinois company was the first group of outsiders to perform in it.

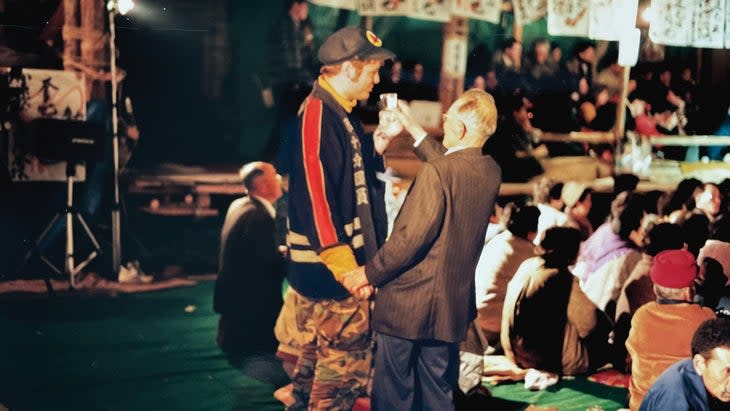

This was an incredible joy and honor, not to mention a mind-blowing treat for a bunch of midwestern college students, most of whom had never left the U.S. (The flight to Japan was my first time on a commercial plane.) Our sensei had taught us a Japanese custom to follow when drinking sake, in which the guest fills the host's cup, then the host refills the guest's, then the guest the host's, and so on. This way everyone enjoys an equal portion of good cheer. But he had forgotten to tell us that you flip your cup when you've had enough, so we were all pretty well cheered up for the main night of the festival.

Kumagai-san, who spent most of his time farming green tea with his family, led a number of priests dressed in masks and kimonos in performing a ritual harvest dance known as dengaku ("pleasure at the rice field") around a large bonfire. I was enraptured by this communal observance of fertility, my fervor bolstered by the booming drums, the gyrating priests, and various celebrants circulating through the crowd of revelers and refilling our sake cups. The mood was raucous and primal, with the priests every so often sweep-kicking at the edges of the bonfire so that the crowd opposite would be showered in sparks, ensuring good health in the year ahead (so they said).

My friends and I came away from our time in Damine with a profound gratitude for the many gifts that had been bestowed upon us. We were mostly spared hangovers, thanks to the cleanliness of the sake we drank. (Life hack!) For me, celebrating with this community of farmers and giving thanks for the yearly bounty that nature provided was the beginning of a lifelong understanding that the mysteries of creation are much more apparent and accessible when standing outdoors in creation itself. Now that was a religious experience.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.