Are We the Next Lost Generation?

My mother, the writer Foumiko Kometani, has taped to her office wall a line from the 1933 film version of Noel Coward’s play Design for Living: “The sorrows of life are the joys of art.” She’s 89 years old; she survived the firebombing of Osaka, and she vividly remembers World War II. The meaning of that sentence and the reason for its placement has always been clear to me. Like many of her generation of Japanese artists and writers, sorrow and brutality are the inspiration for her art. In her case they were also the impetus for her immigration to the United States in 1960—an escape from the experience of, and guilt from, coming of age in a fascist country.

Her eldest granddaughter, Esmee, is 21 and an aspiring musician studying at Bard College. Esmee’s younger sister Lola, 18, is a visual artist who is supposed to start at Parsons this semester. Both, like countless other young people, are now stuck at home because of the pandemic, venturing out only to participate in protests against racial injustice and brutal murders of African-Americans at the hands of the police. I watch them struggle to understand the cataclysm that has swallowed up their youth and the societal inequities causing them to reconsider so many aspects of their lives, from their privilege to their ethnic identities. Theirs may not be a Lost Generation—they have not, in the United States anyway, suffered war or famine (although they’re growing familiar with that other horseman of the apocalypse, plague)—but it is certainly a cohort that shares a powerful, defining universal experience. At a certain point will it be reasonable for them to ask, What will all this sorrow bring forth?

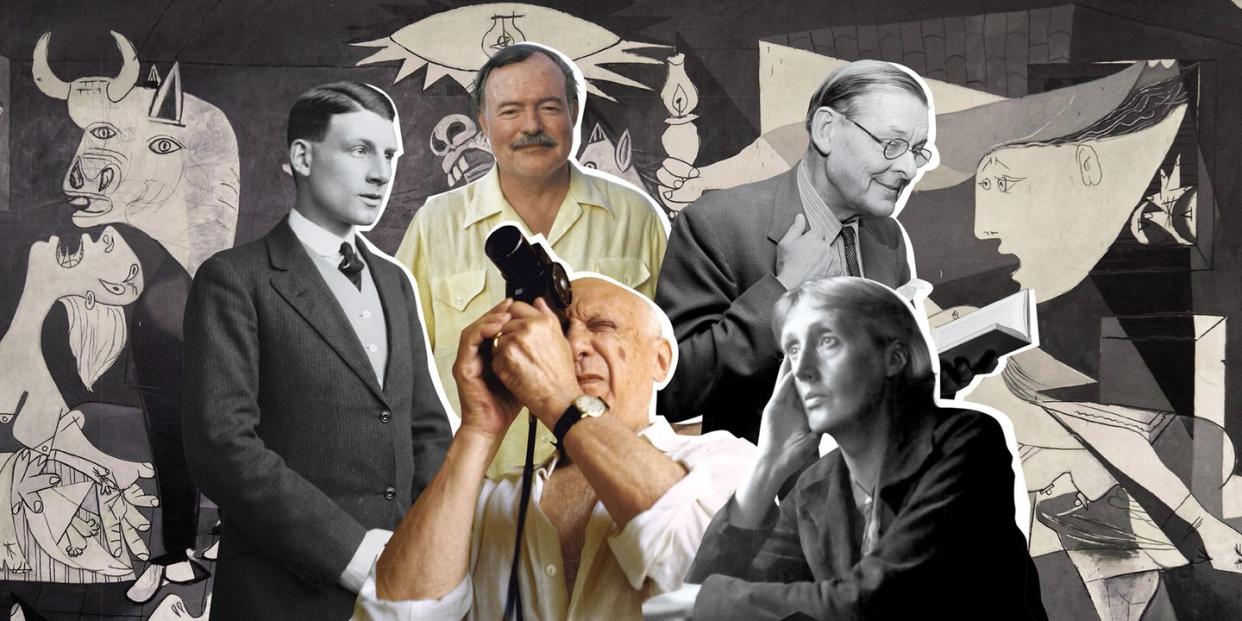

Look back at generations that suffered collective tumult—my mother’s or the one before that—and you can interpret the dark days, months, and years as the seeding for later cultural flowerings. Time and again, mass trauma seems to force artists to think in new ways or even reinvent their forms. Equally important, it makes curators and gatekeepers of art and culture receptive to work more challenging and iconoclastic than they otherwise might have been. Such a cultural transformation wracked Europe and the United States in the aftermath of World War I. (The War to End All Wars even had its own pandemic kicker, in the 1918 Spanish influenza outbreak.)

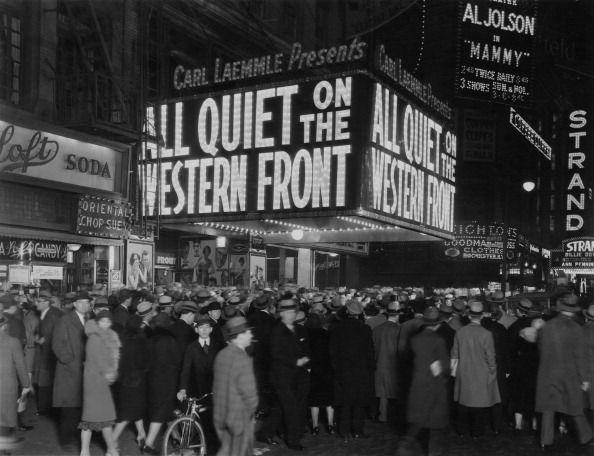

For the generation of artists who had survived, in the squalid trenches at the front or at home, where women took over the workplace and miraculously kept societies functioning, children fed and educated, and bullets and guns in supply, this shared experience would be the subject of groundbreaking postwar art and literature. All Quiet on the Western Front, by Erich Maria Remarque, from 1929, and Le Feu, by Henri Barbusse, from 1916, for example, are two of the greatest war novels ever written.

Remarque’s book stunned readers with its frank depiction of life in the trenches, the betrayal of students persuaded to enlist by their headmaster’s mawkish patriotism, and, most shocking at the time, its jarring shift in perspective at the almost casual mention of the death of its protagonist, a young German soldier, which gave the book an undeniable immediacy and made it so powerful an antiwar novel that the Nazis would make it among the very first works they banned. “In our hearts we trusted them,” Remarque wrote of those teachers who had cajoled them into signing up. “The idea of authority, which they represented, was associated in our minds with a great insight and more human wisdom. But the first death we saw shattered this belief… The first bombardment showed us our mistake, and under it the world as they had taught it broke in pieces.”

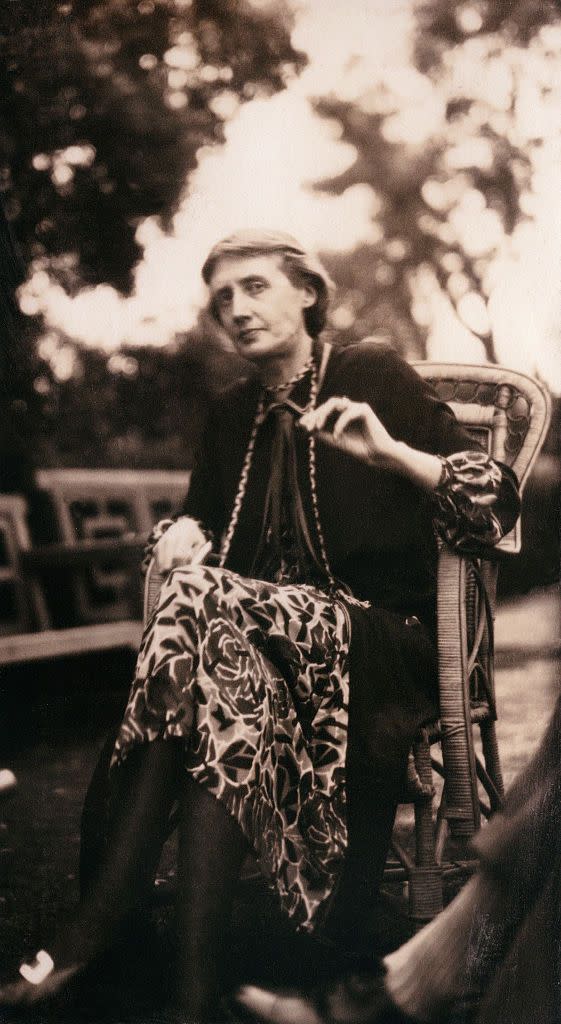

The world had broken. The mood had irrevocably shifted. “Suddenly, like a chasm in a smooth road, the Great War came,” wrote Virginia Woolf in The Leaning Tower, discussing how World War I had transformed literature. First it spawned the soldier poets Siegfried Sassoon, Rupert Brooke, and Wilfred Owen, who lived the hell of the front lines (what Owen, who died in battle, called the “shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells”). These bards of the trenches cleared the way, in a sense, for the modernism of T.S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, James Joyce, and, not least, Woolf herself. “He who was living is now dead. We who were living are now dying,” Eliot wrote in his 1922 masterpiece The Waste Land, perhaps the most pored over and studied poem in the English language.

I can’t claim any particular insight into that work, but I can remind readers, as Woolf did, that it was certainly, insistently, a modern poem. Indeed, the trauma of the conflict seemed to have shifted the earth’s creative axis, to have divided creative history into “before” and “after.” Society itself was irrevocably transformed. The success of the women’s suffrage movement was a direct consequence of the men being at the front and it becoming painfully evident that women could not only do “men’s work” but should be granted a man’s right to vote. In her central, and perhaps most famous, essay, A Room of One’s Own (1929), Woolf would go further, calling attention to the hidden role of women in all literature throughout history, correctly pointing out that we had, thus far, been reading only half the story, as it were.

In theater, the fine arts, classical music, jazz, film—virtually every medium, even those just being invented, like radio—society embraced the new, hungered for experimentation, and became willing to take risks and enjoy the risqué. In fine art, too, the urgency of a work like Pablo Picasso’s 1937 Guernica, in which he used cubism and surrealism to communicate a visceral sense of the horrors of war, made the photorealism of even the greatest prewar paintings, like Thomas Jones Barker’s 1877 Charge of the Light Brigade, seem merely painted men on a painted battlefield.

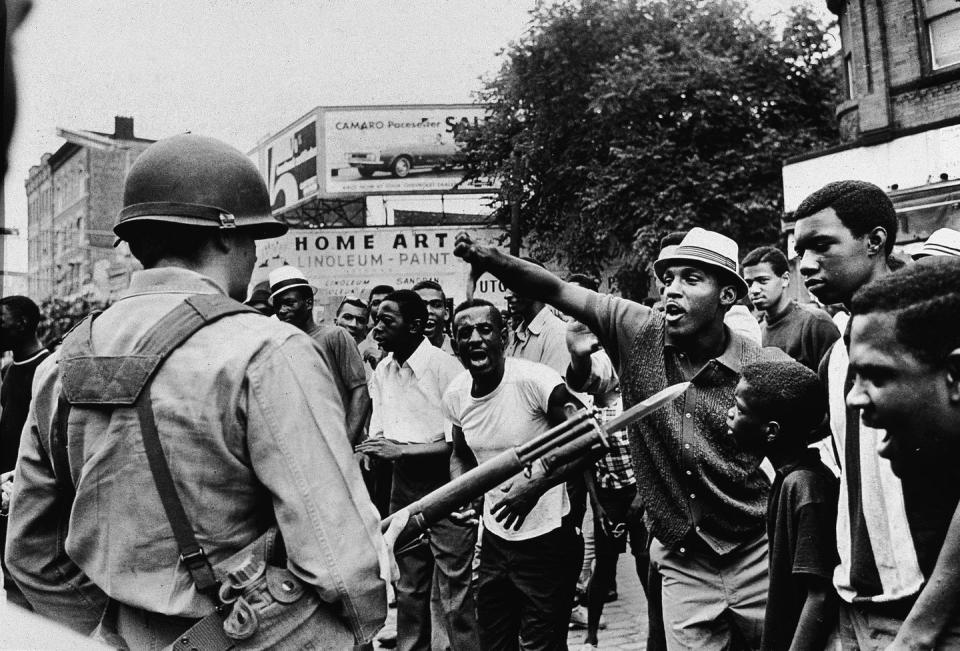

Subsequent episodes of generational turmoil would birth their own lasting cultural awakenings. The civil rights movement in the United States was the continuation of a centuries-long struggle, but African-American writers only began to receive their share of the literary limelight during our nation’s battles to end Jim Crow in the 1950s and ’60s. Writers like Eldridge Cleaver, Ralph Ellison, and James Baldwin wrote with the urgency not just of a generation under siege but of an entire race still in social and economic bondage. Baldwin, in particular, spoke in a manner that for members of previous generations would have been unthinkable, insisting that both the oppressed and the oppressor needed to be liberated from their preconceptions. “The rebirth of the soul is perpetual,” he wrote in his 1953 roman à clef, Go Tell It on the Mountain. He had no choice, he wrote later, but to spend most of his life “watching and outwitting white people. I think I know something about the American masculinity which most men of my generation do not know because they have not been menaced by it in the way that I have been.”

Baldwin often lamented his own state of being a “trans-atlantic commuter,” reluctant to return to the country that he loved “more than any other in the world and exactly for this reason…insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” One day in the late 1950s my father, the writer Josh Greenfeld, ran into Baldwin in Paris, at the American Express office on the Place de l’Opera. They were old friends, and on hearing Baldwin describe his dread at the prospect of returning to America and his worry that he might find it as repellent as before, my father offered a half-joking solution: buy a round-trip ticket.

Baldwin laughed and said, “You’re the first person who suggested that.” Nonetheless, he would spend the rest of his life traveling psychologically on one or the other legs of such a ticket, never finding home in his native land, never being able to forswear it. His voice, however, helped the generations of African-American writers who succeeded him, and in this current moment he seems more relevant, and is perhaps more famous, than when he was alive.

The period of upheaval that feels most familiar to the current moment, as if societal disruptions had makes and models, is the late 1960s, when we lived through a dark and depraved period that was similar to the present in its multiple strains of discord. The 1967 Summer of Love was eclipsed by protests against the Vietnam War and riots in Newark and Detroit, which were soon followed by the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, leaders who embodied the progress for which men like Baldwin agitated. Then, as now, protests provoked a response from a president eager to appear tough on crime that unleashed violence in our cities that predominantly targeted African-Americans.

The turmoil would remake America, as the largest generational cohort in our history, the baby boomers, marched and rebelled together, creating a plethora of shared experiences that should have been the fountainhead for great art. When novelists struggled to capture the moment (Saul Bellow was widely considered the greatest living American writer for much of the 1960s and ’70s, yet he seemed more interested in the metaphysics of being than in documenting social ferment), it was left to journalists to reflect American society upon itself. What emerged was the New Journalism, which required both the elevation, by such great prose writers as Joan Didion, Michael Herr, Norman Mailer, Susan Sontag, and Tom Wolfe, of the nonfiction essay into a literary art form and the reader’s acceptance that journalism had taken a seat at the table of high culture.

One could argue, for example, that Mailer, who had made his name by writing perhaps the first great post–World War II novel, The Naked and the Dead, really came into his own creatively while describing, vividly, his urgent search for a restroom during the 1967 March on the Pentagon, in Armies of the Night. (Mailer’s nonfiction is now considered by many critics to be his best work.)

It is Didion in particular, with her keen novelist eye (and bravado), who is now most often credited with elevating the form, using the techniques of fiction to weave a narrative and being willing to put herself at the center of the story. “On August 9, 1969, I was sitting in the shallow end of my sister-in-law’s swimming pool in Beverly Hills when she received a telephone call from a friend who had just heard about the murders at Sharon Tate Polanski’s house,” she wrote in The White Album.

I came of age in the 1980s, a member of generation X, seemingly doomed to no more wrenching a collective experience than Live Aid or, perhaps, the Challenger explosion, signal events but hardly world wars or global pandemics. (The first cases of AIDS were diagnosed at the beginning of the decade, but it wasn’t until the late ’80s that the nation belatedly woke up to the horror of that disease.)

We were a generation dwarfed by our predecessors, the baby boomers, and then too quickly made redundant by our successors, the millennials. They had 9/11 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, seismic events that are already spawning great novels and journalism. Our cultural contributions were the first to be measured in bytes instead of pages, and all our creations seemed epigones of works already hanging in some boomer’s mansion. Who is the great Generation X writer? Jonathan Franzen? Perhaps, but he already seems a relic, even though he is still in his creative prime. David Foster Wallace? Not only is he dead, but aren’t the millennials trying to cancel him? Anyway, the millennials, with their preternatural mastery of each new app, are already impatiently reaching at us with the hook from offstage.

It is my daughters’ generation, whatever sobriquet it settles upon, that will ultimately shepherd the story of this turbulent era into whatever artistic or cultural form it will take. What they are living through, a worldwide pandemic combined with the joint realization that something is deeply wrong with our society, is not as brutal as a world war (as of this writing, anyway), but it possesses a dynamic and tone all its own.

Years from now these protests and this plague will somehow merge into one communal experience, the wearing of a face mask to a protest a cultural signifier as evocative of a time as flapper dresses and peace signs were for prior generations. And these young activists and creatives and nonconformists will have something that every cohort needs if they are to tell one another their stories: a shared experience, something in common, a sense of where their story should begin and the knowledge that someone out there is ready to read, listen, see, watch. My daughters and their peers might be biologically unlucky, but they are culturally gifted with that greatest of all artistic attributes: a subject.

This story appears in the October 2020 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like