A sickening personal tale of the depths of Nazi brutality

No one expected the Germans to arrive with such speed and without a shot being fired, writes Josef Lewkowicz of September 8 1939. In the small town of Działoszyce, southern Poland, where the teenage Josef and his parents lived, the persecution began immediately.

At first, Jews were forbidden to form groups in the street, and pushed off pavements by Nazi patrols. They were ordered to clean the streets and beaten on the slightest pretext; their shops were looted, their private gold, silver and jewels confiscated. Some were arrested, and disappeared. Finally, in August 1942, it was announced the town would be made “Jew-free”. From then on, no other title than The Survivor would have been possible for 96-year-old Lewkowicz’s memoir (co-written with Michael Calvin), some of which makes for almost unbearable reading.

Sixteen thousand Jews were rounded up. With a languid flick of his whip to the right or left, an SS officer decided who would live and who die. Josef (now 16) and his father lived; the rest of his family, though none of them knew it yet, were being sent straight to their deaths. After marching, hungry and exhausted, through the night, the prisoners in the “living” group were sent to what became a slave labour camp of 23,000 in a Kraków suburb – the first of the six camps Josef survived. (In Kraków itself, by the end of March 1943, only 7,000 of the city’s 68,000 Jews remained.)

Beatings, starvation and other ill treatment became so routine that between 8,000 and 10,000 died. Their fellow prisoners were ordered to strip the clothes from the bodies and search the seams for any hidden valuables. Conditions worsened further when the camp, Płaszów, was taken over by Amon Göth, a 6ft 4in sadist who randomly shot people for target practice and made prisoners watch the public executions of their fellows. “There were so many ways to die that we were enslaved by the task of surviving,” writes Lewkowicz. Once Göth put his revolver to Lewkowicz’s head. “So this is how I am going to die,” he thought – but he woke up in the camp hospital. A kapo (a senior prisoner put in charge of his fellows) had knocked Lewkowicz unconscious and told Göth to save his bullet. Even so, the writer recalls, “I knew better than to linger in hospital. The SS doctors were known to administer lethal injections to patients.”

One day in 1943, his father disappeared – to die, as Lewkowicz would later discover, in another camp, Flossenbürg. Next, after Płaszów, selected prisoners were taken to Auschwitz, including Lewkowicz, and of the 60 people crammed into his cattle truck, only 20 finally emerged. At Auschwitz, much of young Lewkowicz’s work was clearing away bodies for disposal in an incineration pit.

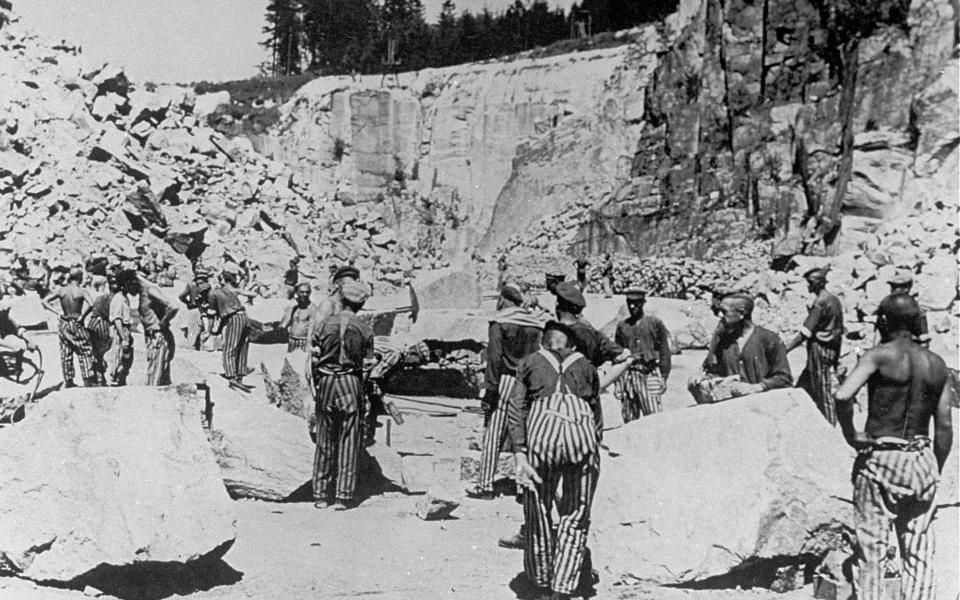

In August 1944, he was sent on again to Mauthausen, in Austria, a camp of 190,000 from 40 different nations. Here prisoners were systematically worked to death, prising sharp blocks of granite from the sides of a quarry then carrying 50kg loads, 11 hours a day, on a ration of one slice of bread and a cup of weak soup. Often, groups would be assembled at the edge of the quarry cliff, where guards forced each man to choose whether to be shot himself or to push the man in front of him over the cliff. Eight thousand Dutch Jews were murdered this way, their death marked down as “suicide by jumping”. Other forms of killing, says Lewkowicz, included “clubbing to death with axes or hammers, being mashed into concrete mixers, or being torn to pieces by dogs specially trained for the purpose”.

Three more camps followed: Melk, Amstertetten, then Ebensee (the latter two being sub-camps of Mauthausen). By the last of these, it was mid-April 1945, and the war was almost over – but among the prisoners left, the daily death toll was still over 350, with naked bodies stacked up outside “living” quarters. Food was so scarce that the prisoners ate grass. Finally, on the morning of May 5 1945, they woke to find that the SS guards had fled. The next day, more than 50 of the cruellest kapos were lynched, before liberation came in the afternoon, as two American tanks rolled into the compound.

It is not surprising that the horrors of the concentration camps are what bubble to the surface in The Survivor. Lewkowicz relives them as he returns to the places where he and so many suffered, but he also gives rein to his thoughts, his philosophy, his beliefs – these are written in a more gentle, flowing style. With his pre-capture life dealt with in some detail, and the last part of this memoir devoted to his post-war adventures after the war, it’s like having two books compressed into one.

In 1946, Lewkowicz managed to join the American military police, helped by his knowledge of German, fairly good Russian and some English. He persuaded the American authorities to allow him to hunt down Waffen-SS men, the worst killers: he could recognise their faces, voices and mannerisms through the disguises many of them would adopt. “There was one name at the top of my list: Amon Göth.”

Many SS men had escaped arrest or detection in the end-of-war chaos, but some found prisoner-of-war camps the best place to hide: by acquiring a different uniform and mingling with another group or regiment, they might not be detected. Dachau, after all, held 30,000 Germans and it was impossible to interrogate each and every one. That was where Lewkowicz began his search, and after about a week, he approached a group of ordinary German soldiers. “Are these all your men?” he asked the officer. “Most, but not all,” was the reply. “There is a stranger who wasn’t with us.” The officer pointed to a cowering figure in a filthy uniform several sizes too small. As Lewkowicz approached, he saw it was Göth, and flung himself on his former tormentor, screaming and lashing out. Later that year, 1946, Göth was tried and hanged.

In post-war Europe, Lewkowicz lived almost from hand to mouth – the family property in Poland had been appropriated by neighbours – then he travelled to South America to join a great-uncle anxious to find any relation who had survived. Resourceful and adaptable, he worked his way up from factory work and street-trading to become a successful diamond dealer, making a happy marriage and finally settling in Israel, where he lives today. How did Lewkowicz survive when so many of his family, friends and fellow Jews died? “In my mind,” he writes, “there was always hope, though I could see none.”

The Survivor is published by Bantam at £20. To order your copy for £16.99 call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books