Native Halloween Costumes Are Offensive, Support Native Designers Instead

In this op-ed, writer Valerie Reynoso breaks down the social and emotional impact of Native Halloween costumes on the Native community, and argues that shoppers should support Native designers instead.

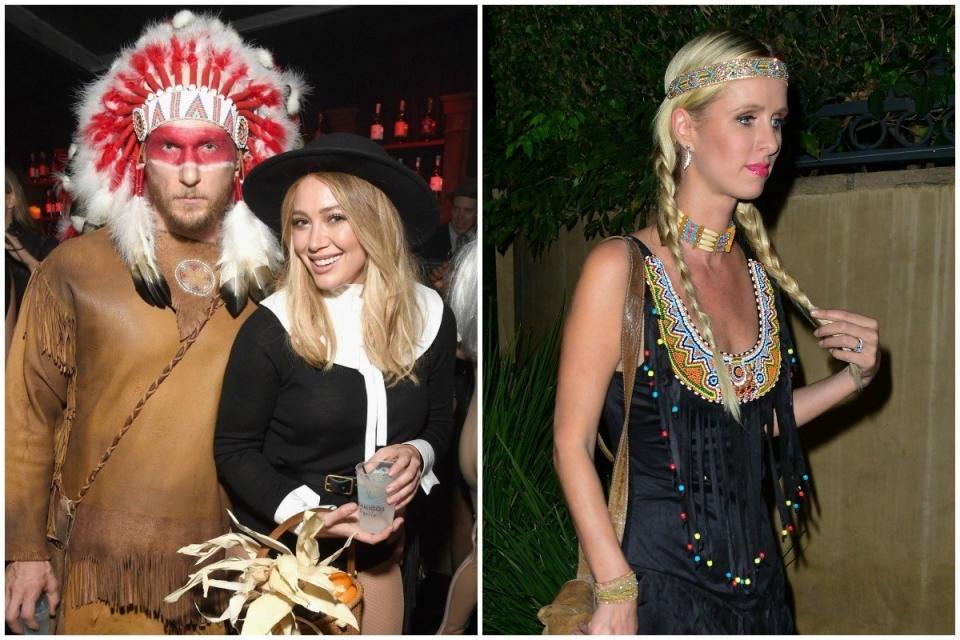

Halloween is the time of year when people dress as something other than what they are, with these costumes sometimes being a satire of oppressed people’s cultures including my culture: Native American. I’m of the Taíno nation from the Dominican Republic and every time I see a Native costume, it makes me feel disrespected and devalued. Native peoples have suffered through centuries of colonialism, capitalist exploitation, erasure, and condemnation — to then be romanticized and whitewashed in mainstream Western culture adds insult to enduring injury. Though appropriators often justify their costumes by saying that it’s meant to be lighthearted, they must realize intention isn't impact — and the impact is the perpetuation of harmful stereotypes about Native people that are rooted in colonial and western tropes. Why wear a culturally appropriative costume when there are so many ways to celebrate Native cultures without disrespecting Native people?

Cultural appropriation is when someone, usually of a privileged socioeconomic background, borrows elements from oppressed groups who have been historically marginalized. Appropriation affords people the privilege to wear someone else’s culture, without having to face the discrimination that members of the culture endure for doing the same. These appropriators are also — intentionally or unwittingly — contributing to the oppression Native people face daily throughout the Americas. Being Native means to be in constant danger: consider Native women being murdered and going missing in Canada and the United States; Indigenous peoples of Central America being imprisoned at the U.S.-Mexico border as a result of the Trump administrations "zero tolerance" policy; Natives persecuted in the migrant caravan coming from Central America, or the Mapuche people being brutally repressed by the Piñera administration of Chile in South America. By wearing Native costumes, people are contributing to the mindset behind Native oppression: the idea that we're alien, subhuman, and somehow less deserving of the respect they give their own culture. They're playing into the imperial narrative of Native extinction, reducing us to being a fantasy of the past that's fit for a costume. And they're projecting the idea that indigenous attire is comical and out of the ordinary, when it is actually sacred and just as normal as Western clothing is.

What's more, appropriation trivializes the brutal history of colonization of the Americas and its legacy today. When European colonizers settled in the Americas, Native peoples of these regions were forced to assimilate into European cultures and Christianity — a practice that still persists today. This cultural and physical genocide was spearheaded through forced baptisms conducted by massacres, enslavement, human trafficking, and the forced enrollment of Native youth into boarding schools to become Westernized. Native spiritualities and cultures were outlawed with the establishment of the new white supremacist order.

Jamestown Commemorates the 400th Anniversary of the Wedding Between John Rolfe and Pocahontas

Getty ImagesAfter stumbling upon the land that would come to be known as Haiti, Columbus wrote in his journal: “They should be good servants and intelligent, for I observed that they quickly took in what was said to them. [A]nd I believe that they would easily be made Christians, as it appeared to me that they had no religion.” He then took six native people as slaves and, as Teen Vogue previously reported, "what followed was a total annihilation marked by thievery, rape, enslavement, and the brutal deaths of indigenous peoples." It was essentially made illegal for Natives to be who we are: we had to fight for the continuity and survival of our cultures and lives in the face of colonialism.

Appropriation is just a different, modern form of Native cultural erasure: it sustains the Western idea that Native attire is only acceptable when worn by a white person and when viewed under a colonial gaze.

Appropriation also aids anti-Native misogyny, which I term misogindigena, through Western tropes such as the Pocahontas and “Sexy Indian Princess” costumes. These costumes perpetuate the hyper-sexualization and exotification of Native women and girls. As proven by letters Columbus wrote in 1500 to Doña Juana de la Torre, a nurse in the royal court of Queen Isabella of Spain and the sister of one of Columbus’ leading conquistador crew members on his second voyage to the Americas, Columbus and the Spanish conquistadors sexually trafficked Taíno girls as young as 9 years old from the Caribbean to ship to Spain for sexual slavery. Columbus stated “A hundred castellanoes are as easily obtained for a woman as for a farm, and it is very general and there are plenty of dealers who go about looking for girls; those from nine to ten are now in demand.” There are other narratives in these colonial journals of the conquistadors brutally raping Taíno and Kalinago women in the Caribbean, which “Sexy Indian Princess” costumes directly stem from and are emblematic of.

The real Pocahontas — whose real name was Amonute or Matoaka, as Pocahontas was her nickname — was 17 years old when she was kidnapped by English colonizers and forced to assimilate into English culture and Christianity. She was also a translator and ambassador for her tribe, the Pamunkey Nation of Virginia, prior to her capture. This history contradicts the colonial, Disney representation of Pocahontas as the hyper-sexualized, adult Native woman who aided the English colonizers from the “savagery” of her own people. Appropriative costumes of Native women breed ignorance and are based off of imperialist narratives written by the colonizers themselves, as it was the English colonizer John Smith who wrote the unverifiable tale about how Matoaka allegedly rescued him from being executed by her father, chief Powhatan.

Given that appropriative Halloween costumes are historically detrimental to Native people, if you're interested in Native culture and fashion, why not show your respectful support for real Native designers who are making strides in the fashion world? If you wish to purchase authentic Native apparel, you can find it at local Native markets, gift shops managed by Native museums such as the National Museum of the American Indian, and from Native designers themselves. Purchasing from Native artisans would be giving money back to the people of that culture who have been socioeconomically deprived and pillaged as a result of colonization. And it shows a genuine interest in Native people’s cultures as opposed to a whitewashed form of it sold by mega-corporations. Ahead, three Native designers to support.

A modern Native American artist using her authentic Native designs to combat cultural appropriation is Jamie Okuma, who is of Luiseño and Shoshone Bannock descent from California. Jamie is well-known for her customized designer footwear that incorporate her heritage’s ancestral beading techniques in a contemporary manner. Okuma uses her craft to demonstrate what real Native designs look like, which on her custom footwear include beaded versions of traditional prints from her tribes, birds, and other prints. Okuma’s work has been featured in numerous art institutions and museums in the United States and Europe, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

Another contemporary Native American designer using her art to create social change is Gabrielle “Gabby” Vazquez, who is of the Taíno Nation from the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. Vazquez is a Brooklyn-based multi-media artist who uses fashion as a medium for fine art, with a focus on language and colonial structures in the Americas. Through her work, she addresses decolonization and works towards the deconstruction of colonial myths. Vazquez is currently a senior at Parsons School of Design, where she is developing her thesis project on Taíno iconography and language.

One of her projects was “Women in Rix (red), with Woven Memories of Caona (gold)" (pictured above) which was presented at Parsons Open Studios in Fall 2017. The project combats cultural appropriation through the utilization of materials and colors prevalent in Indigenous craft, discussing their importance and symbology, and centering the experiences of indigenous groups. Vazquez also makes art commissions at the request of interested customers.

I'm also a Native American visual artist aiming to counter colonialism, westernization and indigenous invisibility through art. I am a multi-media artist based in NYC who uses my work to educate my audience on Taíno history, spirituality and anti-imperialist history. I use my art as a channel through which I decolonize and reclaim my indigenous culture and language that has suffered centuries of violent erasure and genocide, to show that I am not extinct and that my ancestors live through me. I document this journey of undoing systems of oppression that were colonially imposed on my people through my art, so that viewers may also learn about Native culture via an indigenous perspective.

Currently, I am creating a Taíno dress (sketch shown above) inspired by the traditional Taíno nagua, which is essentially a cotton loincloth Taíno people wear on the lower half of our torsos. This dress will be hand-sewn and made of cotton, a crop indigenous to the Caribbean and used in Taíno artistry and spirituality. It will also be hand-beaded using traditional indigenous seed-beading techniques, to reproduce a beaded version of ancient Taíno prints on the upper and lower portions of the dress. The print I am using for my design is based off of that of a pre-Columbian Taíno nagua exhibited at the Museo del Hombre Dominicano (Museum of the Dominican Man) in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, which I viewed during Summer 2017 when I visited my homeland. The purpose of fabricating this dress would be to propagate Taíno cultural continuity and to increase the amount of contemporary, authentic, and innovative indigenous apparel present in the modern fashion world.

I have created fashion illustrations of this dress, which display a Taíno woman wearing a cotton nagua maxi dress that has a beaded Taíno pattern in the upper and lower borders of it. In demonstrating a Native woman in authentic Native apparel, I am conveying that indigenous people are beautiful in our own clothing. This opposes the idea, enhanced by cultural appropriation, that indigenous clothing is only beautiful when whitewashed in mainstream media or imitated by a non-indigenous designer.

As a Taíno woman and artist, I incorporate history, passion and knowledge of my culture into every piece I make. Appropriators who fabricate satirical costumes, by contrast, thoughtlessly contribute to a heavy colonial narrative. Cultural appropriation is historically colonial and racist, but Native American women are taking initiative to bring an end to this repressive practice through our unique Native art and design. If you're genuinely interested in learning more about Native culture, you should support us in this endeavor, this Halloween season and beyond.

Get the Teen Vogue Take. Sign up for the Teen Vogue weekly email.

Want more from Teen Vogue? Check this out: Savage X Fenty Was Everything the Victoria's Secret Fashion Show Should Be