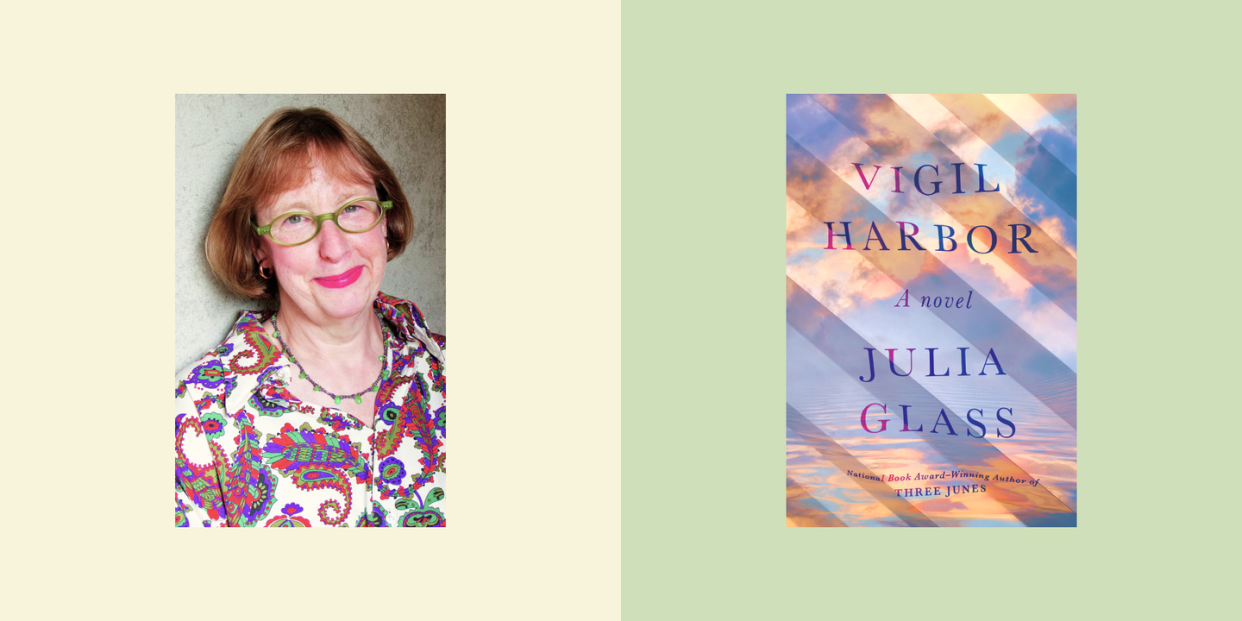

National Book Award Winner Julia Glass’s Latest, “Vigil Harbor,” Is a Dystopian Novel Set in 2034

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

During the past two years of grocery disinfecting and antisocial distancing, anxious lockdowns and reversed reopenings, who among us hasn’t wondered, When will this end? How will this end? Will this end?

And also, for those of us not floating down the River Denial: If we somehow manage to survive Covid’s infinite mutations, how long before climate change, terrorism, and/or war end life as we once knew and loved it?

In her seventh novel, Julia Glass—National Book Award winner for her first, Three Junes—makes addictive, accessible art from these unanswerable questions, going where no author has gone before: into the brave new post-pandemic, climate-changed, terrorized America of 2034.

A lesser author might have modeled this cautionary tale on the disaster movie, using a high-profile metropolis as backdrop, its emblematic skyscrapers and postcard streetscapes starring in stomach-churning, sensational scenes of mass destruction. Not so Glass, whose quiet, inward explorations of the human condition have always been more Fantastic Voyage than Towering Inferno; more psychological and relational than spectacular or apocalyptic.

In Vigil Harbor, Glass’s trademark interiority unfurls in the apocryphal fishing village of the book’s title. The bucolic setting and repeated use of the soothing word harbor seem, at first, to foretell a tale as gentle as a low-tide wave lapping against a barnacled pier. “The harbor itself resembles a long blue parcel held snug beneath a muscular arm against the Massachusetts coastline.”

But then Glass lowers the boom that is the message and the meaning of the book: the intractable calamities that human frailty plus nature’s wrath have wrought, and humans’ responses to those calamities. “The shoreline here is rugged with rock, nothing like the bygone aprons of silken sand…much of that sand recently eroded by pummeling rains and swallowed by storms that no longer repay the ground they borrow.” “As an almost-island, Vigil Harbor has not suffered as badly during waves of contagion as other, landlocked towns.”

Although the novel is peppered with Glass’s distinctive dry wit—lesbian protagonist Petra and her wife, Carly, celebrate their city hall wedding with “lunch at a favorite French restaurant we fondly called The Overprix (rhymes with dicks)”—its dystopian message resounds throughout like a braying foghorn. Sand swallowed by storms. Waves of contagion. In case you were wondering, Glass shows us, life in 2034 is a bitch, not a beach.

The novel opens with a chapter named, as most are, for one of the eight characters from whose point of view the story is told. College dropout Brecht, who has returned to Vigil Harbor from New York following a terrorist attack, recalls, “…The bomber drove his little death truck into the farmers’ market and filled that sky with flash and then smoke. Smoke, but also flying fragments of so many things, things that shouldn’t have been, blown to smithereens.”

Brecht finds his hometown in the grips of a “virus of radical discontent.” “You can have an emotional epidemic, I’ve heard. Or maybe it was dormant stress from home repairs after [climate-change-induced Hurricane] Cunégonde.…”

Having established the ground of the novel—a near-future America in which the very fabric of human memory is shot through with glinting threads of trauma—Glass populates the village, and the book, with residents who speak to us in first person, each bearing bad news from 2034.

Mike, whose marriage was one of Vigil Harbor’s many conjugal causalities, reflects on his post-abandonment options. “New York has lost a good deal of its glow…No malicious attack has matched the scale of 9/11, and for a moment after the global death harvest of the first viral surges, I was among the gullible optimists who thought the calculated acts of violence might just—like passionfruit—be a thing of the past.”

Margo, whose husband absconded with Mike’s wife, attempts to construct her recovery plan. “Today: the first grocery safari I’ve made since The Decamping. It felt, paradoxically, like one of the countless masked-and-gloved expeditions I’d make back in Early Pandemic.… This time I was shopping for one, but McCoy’s Grocery felt like just as much of a minefield, contact with other people a source of dread all over again.”

Brecht’s stepfather, renowned architect Austin Kepner, who specializes in homes built to survive the brutal new normal climate, has a passionate affair with the mysterious Issa, previously the passionate lover of Petra. In Issa’s character, Glass dips her pen briefly and bravely into the well of magical realism.

“You will be my voice,” Issa tells Austin. “You know important people. I am…I’m not that.”

“So what are you?” I said lightly, trying to calm her. “A mermaid?”

“Don’t mock me,” she answered, pulling away.

——————

In a lively email exchange with Julia (“call me Julie”) Glass, she explained the provenance of her new book. “What pushed me to speculate about what our lives might look like a decade from now was a confluence of local weather, national politics, and the deprivations, losses, and extreme fear brought on by a public health disaster.”

Glass went on, “I live in a town along the Atlantic coastline that’s set well above the sea, so we’ve been spared the flooding that’s been overwhelming New England’s seaside communities, and that hit New York in 2012 with Hurricane Sandy. Then in 2015, Massachusetts went through Snowmageddon, a natural cataclysm followed by a man-made disaster: the 2016 election. I decided that my novel had to take place in a community like mine, vulnerable yet sheltered, concerned about its future but also smug.”

Glass tells me she began the novel a decade ago. “Just as I thought I was finishing Vigil Harbor,” she says, “the pandemic hit. On a selfish level, I was upset that this global tragedy had just rendered my novel out of date and irrelevant. But then I understood that the pandemic would give richer texture to a story about people trying to remain hopeful in what could appear to be hopeless times.”

——————

In the novel’s penultimate chapter, Brecht returns to lower New York, the scene of the terrorist bombing he survived, to have dinner at the apartment of his father’s friend Steve, “the guy who took care of me on the day from which my memory saved only a few paltry scraps.” While Steve cooks and chatters, Brecht wanders to a window.

“Center stage is a view of Union Square, a view in which the divide is clear between the surviving old dowager trees along the east side of the park and, to the west, the brand-new junior trees that must have been planted to replace those that died from the blast.”

Steve notices Brecht’s silence and joins him at the window.

Brecht says, “I think I stood right here and saw the smoke.”

“You did. Which was stupid of me. To let you see it.”

“It’s okay,” I say. “I actually had this memory, like carried it around with me, of standing at a window seeing the smoke. I didn’t know where the window was…It was like a piece that lost its puzzle.” I look down at the table, the basket of bread. “I’m hungry, and it smells really good in here.”

By ending the novel this way—illuminating the divide between old and new; between human evil and human good, between alienating trauma and the beckoning fragrance of a homemade meal in the making—Glass makes a characteristically deliberate, methodical authorial choice to execute her mission.

“I want to entertain readers,” she told me, “but if I’ve done anything right, they will also feel recognized and consoled, maybe even galvanized to somehow act differently, more generously, in their own lives.”

You Might Also Like