Nancy Pelosi and the End of Fashion Diplomacy

Oops, she did it again.

On Monday, Nancy Pelosi appeared on Capitol Hill to announce the Democratic Party’s police reform legislation in an outfit that told us exactly what she’s thinking about. Like her fellow Democrats, Pelosi complemented her festive, tomato-red pant suit with Kente cloth, the Ghanaian striped textile. The cloth, one supposes, was meant as a show of solidarity with the black community that has been systematically brutalized by police. But when the camera panned out to show Democrats taking a knee in silence for eight minutes and 46 seconds in honor of George Floyd, the image of congressmen, including several older white men, wearing a traditional African textile made for an odd sight. (A photo of Senator Cory Booker, who opted not to wear one, with his brow furrowed, went mildly viral.)

The Kente stoles were distributed to Democrats by the Congressional Black Caucus; Representative Karen Bass, the chair of the CBC, told reporters that “the significance of the Kente cloth is our African heritage and, for those of you without that heritage, who are acting in solidarity.” (The Congressional Black Caucus did not return a request for further comment.) While the stoles are often worn with academic robes in the United States, many on Twitter wondered whether a traditional Ghanaian textile, which is rich with symbolism for the Ashanti people, is the best representation of politicians’ empathy for the black American experience. As fashion historian Shelby Ivey Christie put it, the textile “comes from Ghana + is their intellectual property—it’s not a U.S. political prop.” Wrote Bossip: “They could have done without this.”

The Kente confusion is the latest example of politicians using clothing to convey what they feel they cannot, should not, or will not say. It is what’s commonly called “fashion diplomacy.” It has become one of the most prominent features of our increasingly visual American democracy over the past decade.

And it needs to end.

Fashion diplomacy has long been a part of being a woman in the public sphere: First Ladies from Jackie Kennedy to Melania Trump have worn specific designers or silhouettes to nod to foreign guests and hosts, and Michelle Obama made J.Crew a key component of her relatability to the average American woman. (It’s not just an American thing, either: Princess Diana made a whole career out of wearing outfits that showed her allegiance to certain causes or allies (or her venom for her estranged husband)).

But the current wave of fashion diplomacy became a regular feature of American political dialogue shortly before the 2016 election, when Hillary Clinton’s Nina McLemore pantsuits suddenly became a window into her elusive public persona. It can be hard to remember that only a few years ago, it was considered frivolous and even sexist to discuss how a politician dressed—a distraction from the “real issues”–but Clinton, hoping to emphasize gender in a way she’d avoided in 2008, cannily used her suits to express a idealistic breed of professional feminism. She often did this with great success, wearing a white suit to accept the Democratic nomination as a nod to the Suffragist movement, for example. But during the Trump administration, which puts a premium on its members’ “straight out of central casting” physical appearances, clothes have shifted from a way to amplify a message to something more like costume, for both Democrats and Republicans. (Finally: a truly bipartisan issue!) Clothing has been a crucial component of Ivanka and Jared Kushner’s campaign to style themselves as the heirs to the Kennedys’ Camelot, as if they are searching through a wardrobe department to dress for the job they want. Though women tend to be the focus of these readings, men are skilled practitioners of fashion diplomacy, too: Prince Harry wears a J. Crew Ludlow Suit to boost his man-of-the-people bonafides, and Donald Trump’s too-long, too-wide ties are, uh, crude expressions of virility.

After Hillary's campaign, the public’s relationship with fashion diplomacy reached a fever pitch when Melania Trump wore her infamous green jacket—the one that read “I REALLY DON’T CARE DO U?”—while visiting detained children in Texas border towns in August 2018. It was such a bizarre gaffe that it seemed it must contain some secret message, a painful, wincing glimpse of what one of history’s least talkative First Ladies was really thinking. Conspiracy theories and deep readings abounded, even within the White House, which insisted both that it meant nothing and that it meant everything. Nevermind that Melania, who once wore a pith helmet on a trip to Africa, has a one-dimensional understanding of thematic dressing: she likely has a section of fatigue-like clothes in her First Lady closet, and, thinking that a Zara moment might make her more relatable than the high heels she was lambasted for the summer before before, pulled it on unwittingly.

Suddenly, it seemed like every politician’s outfit was a treasure trove of secret messages and symbols. And even more freakily, politicians, with their oversensitivity towards the court of public opinion, were quick to play ball. Most male Democratic presidential candidates refused to wear jackets on the campaign trail over the past year, for example—as if people wouldn’t otherwise understand that you’re hard at work unless you actually rolled up your sleeves. (It’s made the straight-shooting style of other politicians look kind of refreshing in their dullness: Andrew Cuomo and Joe Biden just wear the suits.)

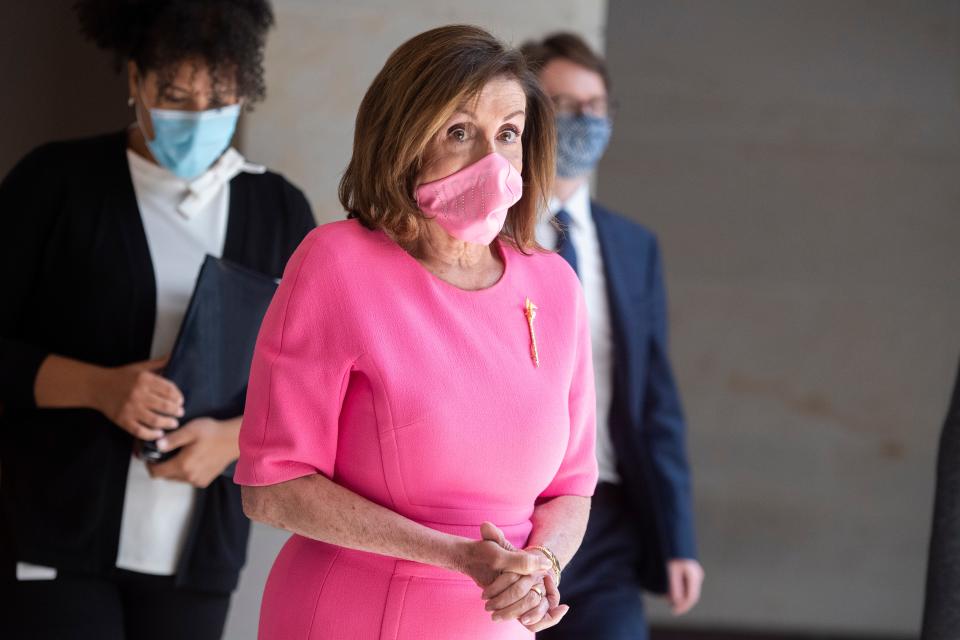

But Pelosi has become the most eager player of the fashion diplomacy game. Last week, she wore a bubblegum pink mask, encrusted with “VOTE” in rhinestones, that perfectly matched her sheath. She’s become a scarf and mask maven, with her coordinating masks for every outfit looking less like a health measure than a petty rebuke to her foes across the aisle and in the White House who refuse to don masks. Of course, she’s found her audience to be more than willing co-conspirators: when she walked out of the White House in a red Max Mara coat in 2018, following a tense meeting with President Trump over the southern border wall, she was celebrated as some kind of vigilante, nevermind that it would be ludicrous to think that a $2,990 coat could somehow be intended as a protest against the president, or that Ivanka Trump’s infamous Bible purse from last week came from the same brand.

If the past few weeks have taught people in power anything about fashion, it should be that gestures matter far less than actions. It’s not enough to use a visual symbol—especially when it’s unclear what, if anything, stands behind it. There are other ways for politicians to show they are doing the work, too: politicians, unlike celebrities, are meant to be clear communicators, and we shouldn’t need to rely on their clothing to know what they’re actually thinking about, or to placate us when it seems that their actions have not gone far enough. Shouldn’t they just be telling us? (In a certain way, you have to respect Melania Trump for just dressing like the rich woman she is, with a love for Gucci’s more conservative pieces, Dior sheaths, and Louboutin shoes. She no longer attempts to bend to anyone’s expectations for a relatable First Lady, and she won’t cosplay as a J.Crew or Madewell mom, either.) It’s no longer enough to wear a scarf, a coat, or a stole, and expect it to speak for you. Clothing can only say so much.

This story has been updated with comments made at Monday’s press conference by CBC chair Karen Bass.

Originally Appeared on GQ