Nancy Cunard Was the Original Renegade Heiress—But Also So Much More Than That

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

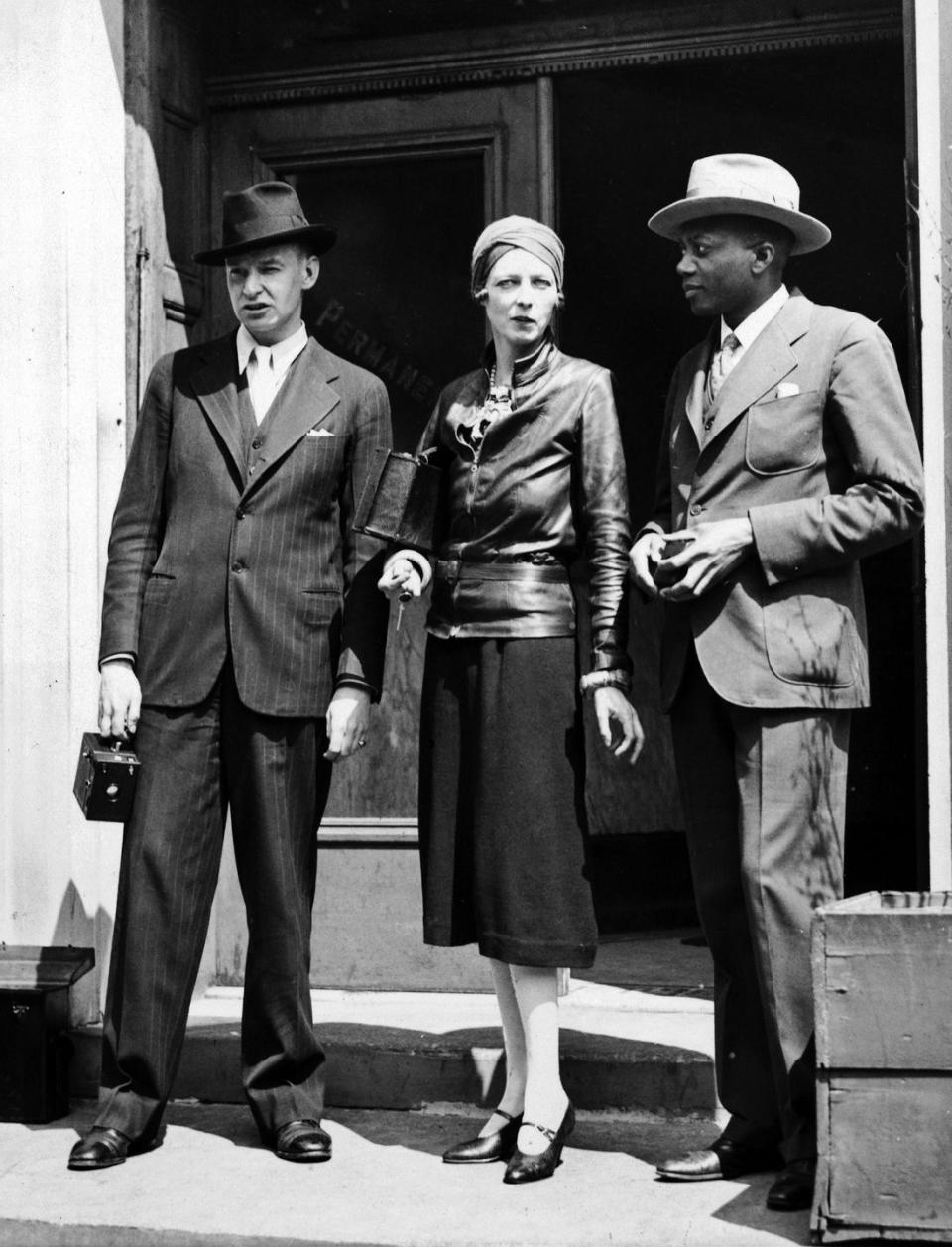

Yes, Nancy Cunard was a rich girl. Her father was the heir to the Cunard Line shipping fortune, and her mother Maud, who later changed her name to Emerald, was one of London’s best-known hostesses. Nancy grew up with every advantage, but that isn’t what makes her fascinating. Instead, it was the way she chose to live her life—among an army of artists, writers, agitators, and rabble-rousers, many of whom she dated—that captivated generations of admirers. Her habit of putting her money where her mouth was, supporting human rights and political freedom in Europe and America alike, has become her enduring legacy. In Anne de Courcy’s new biography, Magnificent Rebel: Nancy Cunard in Jazz Age Paris, Cunard’s hijinks and heroics are explored, in a book that tells the story of a complicated and compelling woman who lived life definitively and became one of the original renegade heiresses.

In August 1928 Nancy Cunard and Louis Aragon went to Venice. Although neither of them realized it, this heralded the end of their affair. For Nancy Venice was a natural destination. All through the 1920s, it was to Venice that the ultra-fashionable of Europe’s beau monde flocked in late summer and autumn. (The Riviera did not overtake it until the following decade.) The railway network across Europe was growing and improving; even Paris trains, chaotic until the mid-’20s, were now reliable, and the Rome Express as well as the Simplon Orient connected Paris with La Serenissima, both featuring luxurious sleeping cars and restaurants.

Once there, anyone from the social world in which Nancy had been brought up could be sure of meeting friends; a mere half-hour in Florian’s café in St. Mark’s Square watching the world go by would ensure that. As for the Lido, where the smart world congregated much of the time, in Nancy’s words it was spectacular: “that blazing Lido strewn with society stars in glittering jewels and makeup, that brilliance of Grand Canal barge parties, those spontaneous dawn revels after dancing in some of the rather sinister new night-bars.” There were endless festivities. The Cole Porters, for instance, were famous for their hospitality. “Dined with the Cole Porters. After dinner they had singers come on the [Grand] Canal under the moonlight. Wonderful moonlight. It was all too beautiful,” wrote Duff Cooper in August 1923. He added thoughtfully, “These perfect moonlight nights in Venice are incomplete without some love affair.”

Nancy’s own love affair, however, was going badly. Between them was what Aragon, still hopelessly in love with her, called “a false situation, perfectly intolerable.” Although Nancy was richer than Aragon, when the publisher Doucet was paying him a monthly salary he could, if not keep up with Nancy’s lifestyle, at least afford to live independently and no doubt pay for meals and drinks from time to time. Now he did not have that, and, while in Paris he could always scratch out a living, in Venice he knew he would be completely dependent on his mistress, something he hated, especially as Venice, with its glittering social life, was entirely different from the trips they had made to Spain or the South of France—both known for their cheapness.

So before going he decided to sell a painting by Braque, La Baigneuse, that on André Breton’s advice he had bought earlier for practically nothing. Since then Braque’s fame had increased and the painting’s value had greatly appreciated; with the money from the sale he would be able to accompany Nancy on outings without loss of self-respect. But the sale negotiations dragged on, and he had to leave with Nancy for Venice before the money came.

In Venice Nancy plunged into the customary round of drinks and parties, a routine of which Aragon, whose usual world was that of the cafés and bars of Paris and the company of his left-leaning fellow Surrealists, was beginning to tire. He was also by now aware of Nancy’s sudden infidelities. Penniless and rather miserable, for him it was not a good start to a holiday. As he later told a biographer, “To explain this it is necessary to speak about all sorts of things I don’t like to say about the character of Nane, and of mine, too…the parties, the Venetian society, and particularly because of this man who followed her and who did not belong to their world…and then the liking of Nane for these odd encounters.”

The tensions between them grew worse. For Aragon the continued nonarrival of the money, which would have given him independence, made their relationship increasingly difficult. “We went to Padua to give ourselves a change of routine—that was pure bloodiness,”Nancy wrote to [her friend] Janet Flanner, who was soon coming with Solita Solano to stay. When Janet and Solita arrived they noted that the apartment was filled with strife, with Aragon packing his suitcase ready to depart, then a reconciliation and unpacking. Nancy was at her worst, vicious and disparaging; Aragon was wretched.

One evening, perhaps to get away from the constant friction, Nancy and her cousin Edward went out to dine and dance.

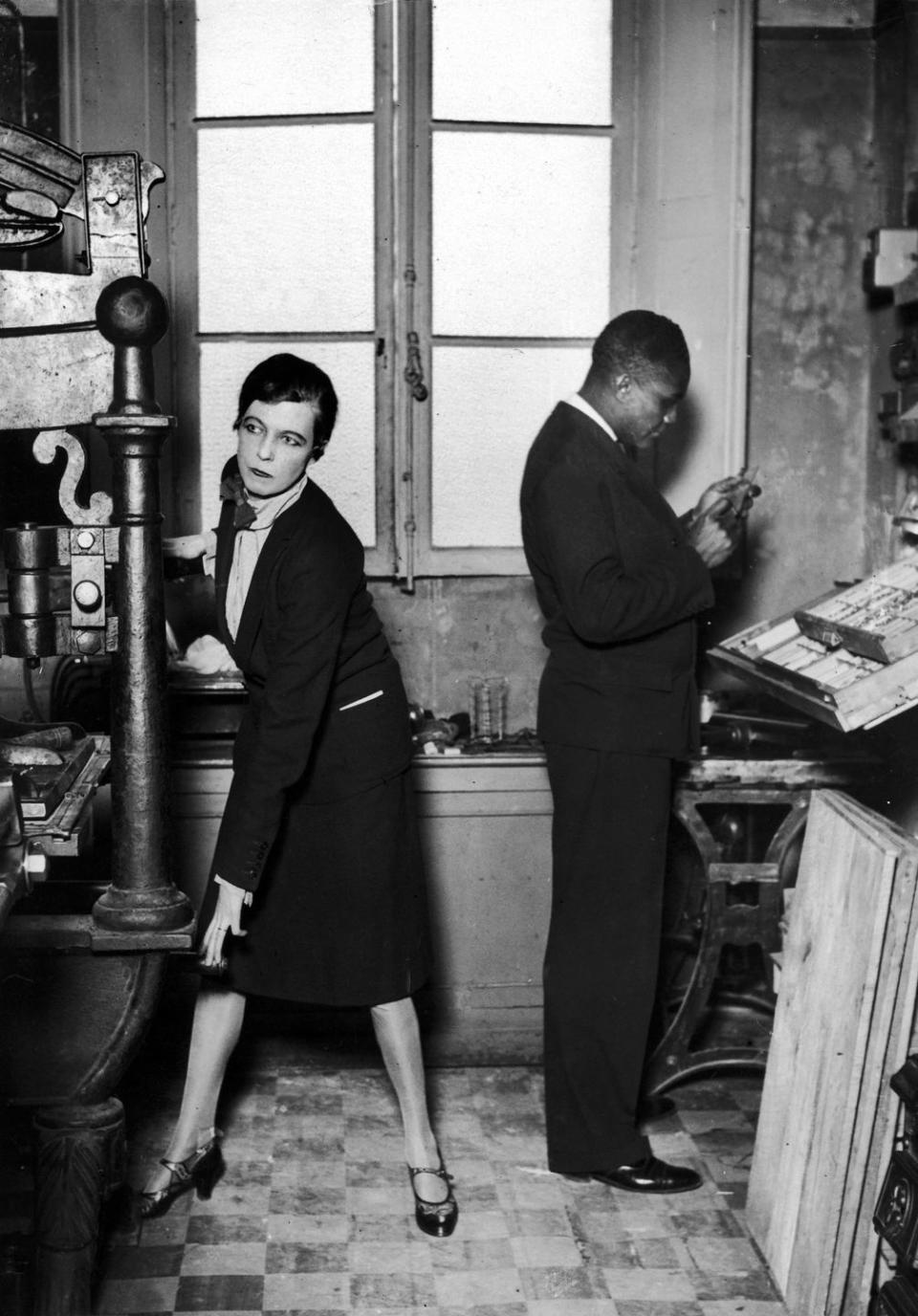

At the hotel they chose, the Luna, a group of Black jazz musicians, hired for eight weeks, were playing. “They were Afro-Americans, coloured musicians, and they played in that ‘out of this world’ manner which, in ordinary English, would have to be translated, I suppose, by ‘ineffable,’ ” Nancy recorded. “Such Jazz and such Swing and such improvisations! And all new to me in style!” For the band, this was a prestigious engagement: the Luna, a few minutes’ walk from St. Mark’s Square, was one of the most fashionable and certainly one of the oldest hotels in Venice. One member of the band, the pianist Henry Crowder, had determined to make the most of this opportunity, to work hard, to avoid temptation—in short, to improve his lot in life. His day began with a French lesson at the Berlitz School of Languages, with two or three hours of piano practice lateish in the afternoon, followed by dinner and then playing at the Luna.

On the day Nancy and Edward first came to dance there, Crowder recorded, “We were all startled to see a most peculiar and striking woman enter the ballroom, accompanied by a tall man.” It was, of course, Nancy. She and Edward thought the band were so good that they came to the Luna night after night. One evening they asked the banjo player, who had finished for the night, to sit down and have a drink with them. Crowder, the last to leave the bandstand, went to fetch his hat. As he passed the table where the three were sitting, Nancy asked him, “Won’t you sit down and have a drink?” He accepted and sat with the other three. So began what would be the most important love affair of Nancy’s life.

Crowder was a good-looking man of mixed Native American and African blood, born in Georgia in 1895, the youngest of the 12 children of a tanner. He had played the piano since childhood: “It just came natural.” But he had also learned to read scores, however difficult. His was a churchgoing family, and he had acquired much of his musical skill singing in church and playing the piano at the YMCA, although he first earned a living as a pianist in Washington brothels. Gradually, through hard work and moving around, he moved up in the world and eventually, with his band, the Alabamians, went to Europe.

A few days after they met, Nancy made her move, telephoning Crowder while he was having supper with the band to ask him to join her for dinner. When he told her he was already eating, she said it did not matter and she would send a gondola immediately.

As the black gondola she had sent to fetch him glided noiselessly over the dark waters, Crowder, unable to speak a word of Italian or to recognize his surroundings, wondered what lay in store. He was ushered into an elegant apartment, where dinner was served; after it, Nancy said she had some things to show him that might interest him. She took him into her bedroom, where she brought out some of her bracelets and beads, often standing close to him.

Crowder, hesitant at making a false move yet wondering if this closeness were deliberate, was suddenly aware that he was immensely attracted to her: “My heart was thumping at a terrific pace. I could feel my blood excitedly racing to my head.” When they said goodbye, she looked at him meaningfully and he tried to kiss her, but she leaned her head away. Feeling he had made a blunder, he turned away, but then Nancy suddenly kissed him full on the lips. He went back to the hotel and played his stint on the piano in a daze.

A day or two later she made one of her restless departures. When she and Crowder were having drinks together, she told him she had to go to Florence to see Norman Douglas. While Nancy was gone, she and Crowder kept in touch by telegram; when she returned and Crowder saw her again, he suddenly realized that “I was infatuated beyond all reason.” All his plans and good resolutions faded away in the heat of this passion. “I love you as I have never loved anyone,” he wrote. Nancy would go around to the band’s hotel and watch them playing their endless card games. She gave them all Venetian glass rings—Crowder got a wonderful green one lined with gold. And when she decided to give a masked ball, she asked them to play.

Nancy’s ball was both fashionable and decadent—theater designer Oliver Messel wore silver eyelashes, an old nobleman was dressed as a mandarin, another fantastic figure rushed about frantically because he had mislaid his little jeweled box, which held cocaine. Nancy’s elderly gondolier was solicited by one of her female guests (“I could have understood if it had been my nephew,” he said to Nancy afterward).

The party ended in a downpour of rain; Nancy asked Henry to stay behind, and they watched the other three Alabamians leave at six in the morning in bright sunlight with their pickups. That night she and Henry became lovers. As they parted after a late breakfast, Crowder realized that “I was infatuated with a white woman. Somehow I felt this woman had something I had never discovered in any other person… I…allowed myself to be held by an invisible power she seemed to possess.”

For Aragon, Nancy’s new affair was literally almost a death blow. Her sudden passion for Henry hit him where he was most vulnerable: his fear of being abandoned. His anguish was such that suicide seemed the only way out. Having studied medicine, he knew the necessary pills to buy and found them at a nearby pharmacy.

Next, he rented a room in a hotel overlooking the Riva degli Schiavoni, where he swallowed the pills. He owed his life to an English friend who, worried by his absence, scoured the city to find out where he might be and managed to reach him in time. Several days later, Aragon decided to try again and went back to the same pharmacy, but this time the pharmacist, either alerted to what had happened or alarmed by his appearance, guessed what he wanted the pills for and refused to sell them to him, saying that the sale of this product was now forbidden.

Magnificent Rebel: Nancy Cunard in Jazz Age Paris

amazon.com

There was only one alternative: to go back to Paris. This time Nancy could not persuade Aragon to unpack, and he left for France at the beginning of October. Ironically, just before his departure the promised check from the sale of his painting arrived, so he now had all the money he would have needed for the life in Venice that he was about to renounce. On the return journey to Paris, he stopped off in Milan, where he went to La Scala to hear Verdi’s Otello, with its central theme of jealousy, six times.

When the Alabamians’ contract ended in the first week of October, at around the time Aragon left Venice, they departed for Paris. Against the band’s advice, and that of Nancy’s cousin Victor, Crowder, persuaded by Nancy, stayed behind in Venice for another 10 days. Aragon might have been cheered had he known that Crowder, within weeks of beginning his affair with Nancy, was already experiencing the same pangs Aragon had felt, when she went off for the night with a young Italian nobleman who was also pursuing her. Not for the last time, Crowder swore that he would tear himself away: “But I never did. There was that same indefinable attraction, that same pulling force, that same something so intriguing and interesting that I could not shake myself loose.”

Excerpted from Magnificent Rebel: Nancy Cunard in Jazz Age Paris by Anne de Courcy. © 2022 by the author and reprinted with permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

This story appears in the March 2023 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like