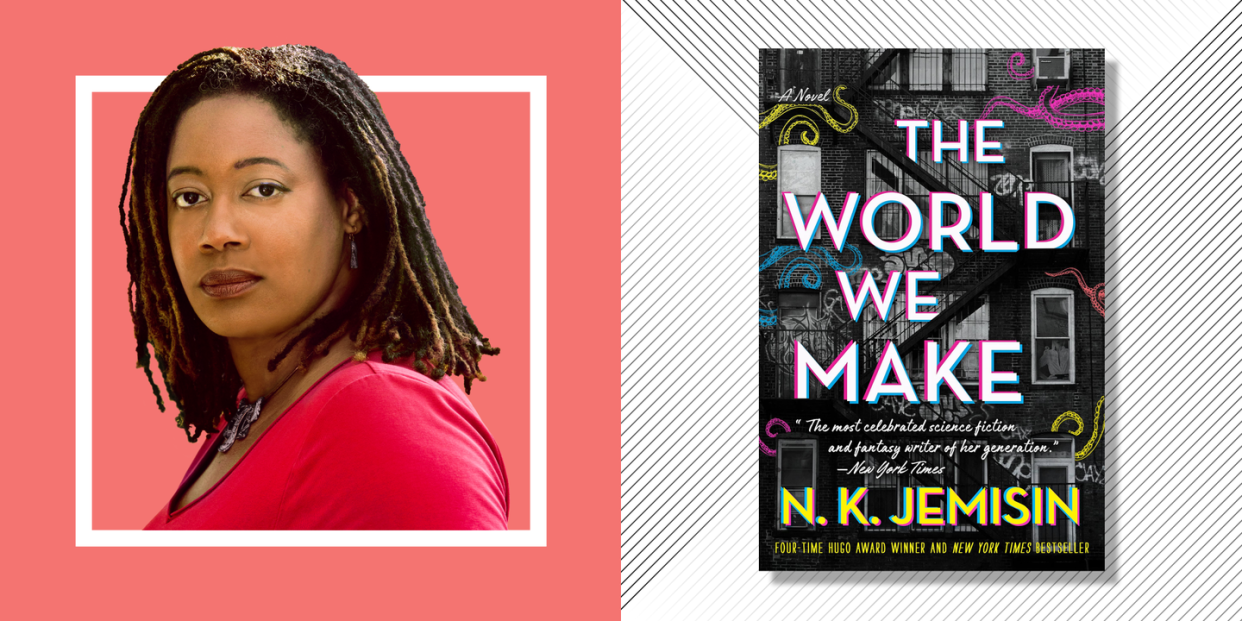

N.K. Jemisin’s Novel “The World We Make” Reimagines New York

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

“When you’re writing a story that is set mostly in the real world—apart from tentacle monsters,” says Nora K. Jemisin, “you have to be ready to change. The real world isn’t going to stay static.” The process of writing her new novel, The World We Make, involved unexpected pivots. As the sequel to The City We Became (2020), in which superhero-like avatars of New York City and its individual boroughs battle the aforementioned monsters, it was originally going to involve a conflict between the city and what Jemisin calls “a demagogue president who attacked New York in the media to elevate his own political position. Then Donald Trump actually did that.”

Unwilling to seem influenced by the 45th president, Jemisin changed the plot point to a mayoral election. In The World We Make, the avatar of Brooklyn, a Black, middle-aged hip-hop emcee turned lawyer, goes head-to-head with a far-right, anti-immigrant candidate. Meanwhile, Brooklyn and the other avatars continue to try and thwart the monsters’ mission to turn New Yorkers into reactionary zombies. Together, the books make up a duology that’s much lighter in tone than Jemisin’s celebrated post-apocalyptic Broken Earth trilogy (2015-17), which won her an unprecedented three Hugo Awards from the World Science Fiction Convention. On the phone from her Brooklyn home, Jemisin tells Oprah Daily about her new brainy romp, which addresses familiar, thorny social justice issues in adventurous ways.

In The World We Make, you’ve taken the familiar trope of “aliens trying to colonize Earthlings” and presented it as gentrification.

I grew up with gentrification discussions all around me—but then, I hung out with a bunch of Black artists and revolutionaries. The issue is reaching critical mass in the 21st century because we're seeing the harm that it does. Cities are the canaries in the coal mine. We are now seeing large corporations buying up starter homes in small towns and urban and rural areas—the exact same thing that has been happening in large cities. The systems in place are going to raise prices to the absolute maximum of what people can afford—or beyond—and screw everybody else. I think people have forgotten that amid all the urban-versus-rural rhetoric. There are a number of people in our society that genuinely perceive the Other to be the enemy.

The avatars of the boroughs are all very different from one another, in terms of age, race, social class, and more. They’re tasked with bridging the gaps between them and fighting the homogenization of New York.

I was trying very hard not to suggest that any one borough is better than any other. They all think that they’re the best, and that the other boroughs are terrible. That’s what New Yorkers are like. At the end of the day, we all have to work together, and it’s difficult for some folks to accept that. They’re all New York. I guess that’s the core message [of the books]—to the degree that I want to send a message.

Without giving too much away, the avatar of Queens is a theoretical physicist, and her way of seeing the universe is important to the way the avatars approach their battle with the monsters.

I don’t know that this is a science thing. More of it was, “Why don’t we try a paradigm shift in how we think about the problem?” The science is a means to that end, but I guess that’s probably reflecting my own, maybe naive, belief that a lot of the problems we have are caused by differences in perspective, and if we are able to step outside of ourselves and consider a different way of thinking, then at least we will understand the other person, even if we continue to disagree.

This book picks up on a theme you’ve previously explored in other works—about what it would mean to ensure the safety of the many by sacrificing the well-being of a relative few. I’m thinking of Ursula K. Le Guin’s story “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas,” which famously deals with this issue, and which you’ve previously responded to, in fiction.

I am constantly wrestling with the concept of “What does it take to make a society that cares about everybody?” A society in which everyone is considered important, valid, and worthy of life, health, and happiness. Science fiction excels at being able to imagine other worlds, ways of being, and ways of living—and I have real trouble imagining a society that recognizes that people are what make us strong. What would a world look like where everybody gets enough food, everybody has had a decent education? Our world forces unnecessary choices on us. Can you have a society where everybody is treated well, or must someone suffer? Must there always be an underclass? Must there always be a downtrodden?

The World We Make: A Novel (The Great Cities, 2)

amazon.com

amazon.comAs a writer, to what extent are you interested offering answers to such questions?

At the end of the day, I am here to entertain people. It’s just that my idea of entertainment involves hard questions, so I answer them to the degree that satisfies me. I suspect, ultimately, it’s going to be that my entire career is the answer. I am throwing out different examples of what can be and the pros and cons of each. In the Broken Earth books, we see the detritus of a utopian-ish society that, like Le Guin’s “Omelas,” depends on the oppression of a single group of people. And even when it doesn’t have that single group of people to oppress, it literally creates its own underclass. There’s a tendency in science fiction to suggest that our technology will save us—that if we just become eco-friendly enough, all our problems will fall away. Even when our technology improves, if we haven’t fixed that part of ourselves, the world will still be completely screwed up. I’m throwing the question out: “What are you willing to do if you want a better way?” I will continue to explore it, and that may take the rest of my life.

You Might Also Like