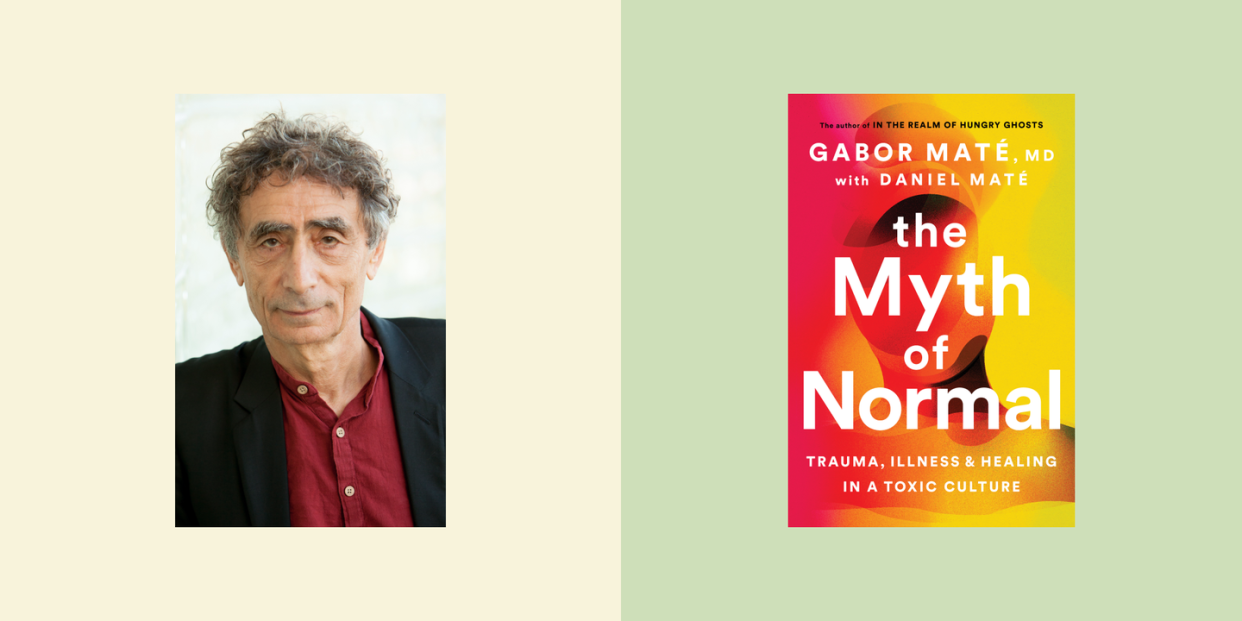

In “The Myth of Normal,” Gabor Maté Discusses the Rise in Trauma-Related Illnesses

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

In the mid-’80s, Gabor Maté, MD, began seeing a patient, an Indigenous Canadian woman named Mary, at his office in Vancouver. As a family physician, Maté often knew his patients before they became ill. In this case, Mary’s first signs of illness pointed to Raynaud’s, a disease that affects blood circulation. But the disease progressed, and Mary was eventually diagnosed with scleroderma—a chronic but rare autoimmune disease that hardens connective tissue. Maté had known Mary for about eight years when he tried something new: He asked her about her past.

“I just had this hunch, because she was so quiet and reserved,” Maté told Oprah Daily. “So I thought, Well, what is she so quiet about? I said, ‘I want to hear about your life,’ and she told me about her traumatic childhood.”

After this encounter, Maté began to notice a pattern among his patients that “opened the floodgates.” “Her story about a traumatic childhood was repeated in everybody I spoke to with a chronic illness, from autoimmune disorders to malignance,” Maté said. “It wasn’t accidental.”

Following his instinct, Maté learned more about the connection between trauma and illness. Today, he’s a world-renowned trauma expert and the author of multiple books focusing on the subject. The Myth of Normal, Maté’s new book, explores factors behind the rise of what he calls trauma-related illnesses. The term trauma—now part of mainstream conversation—originates in the Greek word for “wound.”

“It’s a psychic wound,” Maté explained, which can be inflicted through anything from physical to emotional abuse. (Neglect is an important source of trauma, for instance.) But it is not the event, per se, that is important, Maté argues—“it’s the wound that you sustained.”

Maté’s professional line of inquiry spurred him to take a deeper look at his own history. “I was a successful physician, but I was depressed and unhappy,” he said, “And I began to ask myself, Well, what's going on here?” He traces his trauma back to when he was just an infant and his mother gave him to a stranger for about two months during the Nazi occupation of Budapest. “The wound is not that my mother gave me to a stranger,” he explained. “It’s the meaning an infant automatically makes, which is that I’m not lovable. I’m abandoned. I’m not wanted.”

A look back: Trauma and illness

While there is a genetic component to disease, our environment and upbringing— everything from facing poverty to racism to urban blight—in large part determine what happens to these genes. “Experience, in other words, determines how our genetic potential expresses itself,” Maté writes.

He believes that every diagnosis, from depression to ADHD to PDSD to bipolar disorder, is rooted in trauma.

This idea didn’t used to be so controversial. In the mid-1850s, a British surgeon named James Paget observed that “deep anxiety, deferred hope, and disappointment are quickly followed by the growth and increase of cancer.” Depression, as well, was an additional factor in cancer development.

And in a 1938 speech to a Harvard Medical School class, later published in the AMA, the researcher Soma Weiss noted that “emotional factors are at least as important in the causation of illness and they have to be an important part in the healing of it.” Maté notes that “physicians have been noticing these things forever.”

Stop being “nice”

Maté’s observation about the link between “niceness” and chronic illness has been the subject of research. In a 1998 presentation at the International ALS Symposium on ALS/MND, the story of a group of nurses at the Cleveland Clinic was presented, illustrating this phenomenon. The nurses began to notice trends among their patients—“‘I’m afraid this person has ALS; she is too nice,’ they would jot on the patient’s file. Or ‘This person cannot have ALS; he is not nice enough.’ The neurologists were dumbfounded,” Maté wrote. But it turned out that their hunches were on point.

“When I see really nice people, I worry about them,” Maté said. “What that niceness is, is the repression of healthy anger. [The research shows] that the more anger ALS patients express, the longer they live, for example.”

A 1965 survey showed that people with rheumatoid arthritis—another chronic disease— displayed “an array of self-abnegating traits: a ‘compulsive and self-sacrificing doing for others, suppression of anger, and excessive concern about social acceptability.’” And even in a survey of 150 people with melanoma, patients were found to be “excessively nice, pleasant to a fault, uncomplaining and unassertive.”

“Society’s shock absorbers”

Given these personality traits, it shouldn’t be a surprise that women are at higher risk for chronic illness. Stress, Maté says, plays an “incendiary role” in whether or not a genetic predisposition will result in illness.

And the gender gap has been borne out in the research. “Women take twice as many anti-depressants, get 80 percent of autoimmune disease, they get more chronic illness, more chronic pain than men do,” Maté said.

Another example: In the 1930s, MS by gender was 1:1. Today, for every male with MS, there are over three women. This is a genetic disease, Maté says, and genes don’t change in such a short period. The only other explanation, he says, is the degree of stress that women today face.

Yet women’s stress is often overlooked, Maté argues. “How many women are asked during prenatal checkups about their mental and emotional states, what stresses at home or on the job they may be experiencing?” he writes. “How many future physicians are even taught to pose such questions?”

Maté referred to a recent New York Times piece calling women society’s “shock absorbers,” to help explain. During Covid, he said, on top of their own duties, women “took on alleviating the stress of their husbands and their children,” Maté said. “And they felt guilty when they couldn’t successfully do so.”

“Women have always played that role in this patriarchal culture,” he said. “It’s a society that imposes a certain expectation on one gender. “

Institutional inertia

Maté is frustrated with the medical profession. While there have been many scientific studies highlighting the link between trauma and illness, doctors still focus on “biological psychiatry,” he said. “There’s almost like a wall between science and practice. Western science has more than proved it. And we still don't practice it.” A well-known Harvard psychiatrist, for instance, told Maté that “to talk about mind-body unity is to jeopardize your career at Harvard.”

“That’s my whole beef with my profession,” Maté said. “We keep talking about evidence-based practice, but there’s vast evidence that’s totally ignored.” He calls resistance to these ideas “institutional inertia,” and challenges medical training, as well, to integrate them into the curriculum. If the medical profession could get on board with the evidence, Maté argues, it could help heal the effects of trauma—both at an individual and a societal level.

“Responsibility can and must be taken,” he writes.

You Might Also Like