The “Muse Squad” Author Visited Her Child’s School Library and Discovered This Upsetting New Reality

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Last month, during a parent conference at my fifth-grade daughter’s Miami elementary school, her teacher pointed to an empty bookcase. “Look at my library,” she said. “They took everything.” Her eyes filled. I was speechless. She explained that all reading material now had to be vetted by an administrator before students could be exposed to it. Books that she had curated for years were essentially found guilty of harming children until proven otherwise. Making matters worse, the vetting process was obscure. “I don’t know when or if I’ll get my books back,” she said.

That afternoon, I asked my daughter if she’d noticed the classroom library had disappeared.

“Yeah. Where’d they go? We used to get to choose books from the shelf when we finish our classwork.” She looked confused as she explained, “Books are missing from the media center, too.” So this was why my daughter hadn’t come home with a new reading book the past few weeks, something she’d done weekly since starting in Miami public schools as a kindergartner.

I explained what was going on, to the extent that I understand it. Her classroom’s empty bookshelves are just one example of how some Florida schools have responded to HB 1467, which governs the selection and discontinuance of reading materials in public schools. Under this law, members of the public may review books available to students and request to have them taken away. How many complaints does it take to pull a book? Only one, and that person doesn’t have to be a parent or guardian of a student. After the objection is filed, the book must be removed until a hearing either clears the material or finds it inappropriate, leading to a permanent ban. Many schools, awaiting clarity on laws vague on procedure, are taking a proactive approach, removing the reading material before complaints are lodged.

“My teacher cares about us. She wouldn’t put a bad book in the classroom,” my daughter protested. A worrier and a rule-follower, she thought her teacher had gotten in trouble. I reassured her that this wasn’t the case; we talked about the new law, and how in some other places in Florida, many more books had been removed. “Which ones?” she asked, curious now.

Searching online, we found the lists of challenged books. One had 176 titles on it. She spotted some of her favorites right away. “Islandborn?” she gasped. “Why that one?” Though she has largely outgrown picture books, Junot Díaz’s Islandborn, illustrated by Leo Espinosa, remains one of my daughter’s favorites. It’s a beautiful story about a Dominican girl who learns about her history through the stories her neighbors tell. It’s a tale that conjures the sights and sounds of La República Dominicana and recalls the impact of the Trujillo dictatorship.

I answered her what I believe to be true. “Racism, that’s why. There’s nothing in this book that is harmful to anybody. But I think some adults are just not comfortable having their children reading about someone who doesn’t look like them.”

“Nobody can stop me from reading it,” my little spitfire insisted.

“You’re right,” I said. “I can buy you this book, and you can read it whenever you want. But when books are taken from classrooms and libraries, it’s hard for lots of other kids, who might not have known about them already, to discover them.”

She was thoughtful for a moment. “I think some parents are afraid their kids will feel bad if they learn about the past. But that’s wrong. They should let their children read those stories and then talk to them about it afterwards. Kids are tougher than adults think.”

Indeed. They’re smarter, too.

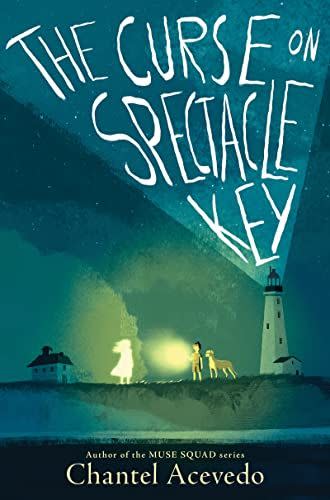

My daughter happens to have a mother who prioritizes reading. An author and a professor of creative writing, I write books for adults and children. Access to books will never be a problem for either of my daughters. But as a product of Florida public schools, who sends her children to Florida public schools, I’m shocked not only that books are being withheld from students but also that changes happened so quickly. I spent much of last fall reading to nearly 1,000 South Florida schoolchildren, sharing my novels for kids, Muse Squad and The Curse on Spectacle Key. In one school, a little boy asked me, “Do you think I can be a writer, too?”

“Of course,” I told him, promising to read all the books he’d write someday. His face was pure sunshine.

In another school, a girl had a request. “Can you write another Muse Squad book? But make the main character Colombian like me?”

“You’d make a phenomenal muse!” I told her.

Those school visits happened last fall, before the onslaught of censorship laws took effect. I got the chance to encourage many young Floridians to read, write, and imagine themselves in stories. Unfortunately, when I volunteered to visit my daughter’s school for Literacy Week last month, I was told that having an author visit was no longer allowed without going through, once again, an unclear “vetting process,” which wouldn’t happen anytime soon.

The Curse on Spectacle Key

amazon.com

“That’s not fair,” my daughter complained when she found out. “You’ve been to lots of schools. I want you to come to mine, too.”

“Things are different now,” I said. She rolled her eyes. She’s almost 11, and the eye rolls are new, a sign of the teenager-to-come peeking at me from the future. I wanted to roll my eyes, too, at all of it—the political posturing, the amorphous, flavor-of-the-day laws that changed so quickly one couldn’t keep up. I worry about teachers working in a climate of fear. More importantly, I fear for Florida children with limited access to libraries and no access to bookstores. For some kids, school is the only place where the books are.

There is a scene in The Curse on Spectacle Key where the young protagonist, Frank Fernández, discovers that the antagonist has been destroying books to cover her tracks. He takes the ruined books to the librarian, who tells him, “…when a story gets forgotten, a part of the world goes with it.” Today, it feels eerily like that scenario is playing out in my home state, in classrooms across every county. At the end of my novel, the villain gets her comeuppance. The books are saved, and a beacon of light shines on truth and the value of knowledge. My wish for my daughter and young readers in Florida—and everywhere—is that life might imitate fiction: that they, too, may have their happy ending, with the freedom to read.

Chantel Acevedo is the author of novels Love and Ghost Letters, A Falling Star, The Distant Marvels, which was a finalist for the 2016 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction, The Living Infinite, Muse Squad: The Cassandra Curse, and Muse Squad: The Mystery of the Tenth. Her latest is a middle-grade novel, The Curse on Spectacle Key. She is professor of English at the University of Miami, where she directs the MFA program.

You Might Also Like