Murder, Muggers, and Rottweilers: Stories From My Best, Worst Apartment

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

J. D. King, the tall drink of water I met at Cutler's Record Store in early December 1976, had passed me his address and phone number that day. I proceeded to write him long letters on yellow tablet paper expounding on my experiences — about seeing bands at CBGB and Max's and hoping sometime soon to be on those stages, starting new wave punk rock fires for the world to be scorched by.

By the late summer of 1977, J.D. — along with some of his RISD pals had relocated to 85 South Street — a loft space at the very tip of Manhattan, overlooking the infamous fish markets, where trucks and trolleys full of that day's catch were delivered onto docks lit overhead from midight until morning.

Spending more and more of my time at the South Street loft, I scoured the Village Voice for a place of my own.

I could live with an old man rent-free if I didn’t mind taking care of him: walking him, feeding him, giving him his meds. Economically sensible as it was, it seemed depressing, possibly dangerous. I had never heard of anyone living to tell such a story. I passed.

After looking at some real ratholes, I settled on a third-floor walkup at 512 East Thirteenth Street between Avenues A and B. The rent was $110 per month, a manageable enough sum—if I could land a job.

The building was typical for the East Village in 1978, especially for the stretch that residents called Alphabet City. No buzzer system at the door; tiny black-and-white-tiled floors, all chipped and grimy. The tenant above me was a barely functional ex-con and drug addict who had a couple of high-strung rottweilers, which he would drunkenly whip and yell at throughout the night. Above him lived an alcoholic couple who stumbled up and down the stairs. When I crossed their path, they would urge me to take a sip from their sloshing bottle of booze. The woman once began screaming maniacally in their apartment, then proceeded to climb down the fire escape at the front of our building, yowling—

“Help! Help me!”

She tried to open my window, sobbing and bleeding, begging me to protect her from her husband, who had evidently smashed a bottle over her head. I noticed him trundling down after her, just as drunk and clumsy as she was, trying to grab her by the hair and drag her back into their hell zone. I didn’t own a telephone so I couldn’t call the cops. I pretended not to know how to open the iron gates that barred the window.

The ex-con upstairs had a strung-out buddy with no teeth who would hang with him once in a while. He would see me, cackle, and call me “Slim.” I must have amused him, the skinny, tall, corn-fed boy just out of his teens living in this godforsaken building. One afternoon, I ducked out of the rain into a doorway on Avenue A, only to find no-teeth guy standing there as well seeking refuge. He was delighted to see me — Slim, of all people! He told me that I should think about selling drugs for him and his friend. He said I could make good money. He added that I could fuck him in the ass if I wanted —

“I’ll suck your dick too.”

I politely turned him down before leaping back into the downpour and heading home.

Each time I approached the corner of Avenue A and Thirteenth Street, I would break into a sprint to my doorway. It ensured, among other things, that I wouldn’t get stopped by the local teens, who thought nothing of ganging up on a new guy in the neighborhood, mugging him for money or kicks. I would be on high alert whenever I headed east toward Avenue B too, a crime scene waiting to happen. I took a chance late one night, walking quickly to a bodega on Avenue B and Thirteenth to grab a pack of cigarettes and a can of Pepsi. On the way back, three kids strolled by, all of sixteen years old. One of them eyeballed me and slapped me on the back, saying, “Hey,” before continuing toward Avenue B.

I picked up my pace, and sure enough the kids backpedaled, surrounding me. They wanted money — ridiculous, as I had probably three dollars on my person. They threatened me with a knife, and I froze. One boy reached into my back pocket and took my wallet; another snatched my bag with the Pepsi and the cigs. They said if they saw me again, they’d kill me, then ran off laughing and yelling, throwing the soda can past my head and onto the street, where it sputtered. I swooped it up and bolted the half block back to my apartment, shaken and terrified. After gathering my senses, I opened what was left of the Pepsi, slowly sucking on its fizzy sweetness, wishing I could smoke a thousand cigarettes.

For weeks I was gripped with paranoia whenever I left my place, mostly from the possibility of seeing those same street kids again, whether in the neighborhood or on a nearby L train subway platform—but it never happened. I had a slow, sober realization. The demons at play in this teeming metropolis were largely figments of my imagination. The crime and violence were real, but they were more or less arbitrary. Also, I probably shouldn’t be walking alone around Alphabet City at three in the morning.

The drug-dealing dude with the rottweilers disappeared one day. It was after I had heard a relentless, low moaning outside my doorway, coupled with an insistent thumping. The sounds from around the neighborhood were always disturbing and alien, so I put up with it for a while, but I eventually opened the door to see what was going on.

I found the toothless guy who had propositioned me lying on his back, his feet crumpled against my door. He must have been bleeding for some time from some unseen wound, because the entire hallway was swamped in blood. I sensed that he was expiring, his leg jerking spasmodically against the door. I leaped over the lake of blood and ran upstairs to bang on the ex-con’s door. I told him his friend was in trouble. He hurried down, eyeballed the situation, and told me he would take care of it. I leaped back over the bloody dude and into my apartment, staying there for as long as I thought it was safe.

I could hear him dragging his friend’s body—clunk, clunk, clunk—up to his room, then the thunk of it hitting the floor above my ceiling. Eventually the landlord appeared with the police, and I told them what I saw, nothing more, nothing less. Cleaners arrived, scrubbing and disinfecting the hallway, but there would always remain streaks of dried blood in the cracks of the aged tile. The guy upstairs soon vacated the building, escorted by cops, his dogs mysteriously gone with him.

A single mom soon moved into the building, one of the only other white residents, the building primarily occupied by Latino and Black tenants (much like most of the neighborhood). She had two little kids who never seemed to attend school. She was also a heroin addict. The last I saw her was while she was pushing her baby daughter in a stroller along First Avenue, obviously on a junk nod.

Her little boy would sometimes knock on my door, with all the innocence of a ten-year-old as he came in, and we talked. Within a couple of years, I would see him performing magic tricks in Tompkins Square Park, hoping to cadge a bit of coin. A few years later I would be hanging with a few people on the sidewalk in front of the Saint, a venue the musician John Zorn had founded to present free improvised music. I watched as two kids began hassling a friend of mine, poking at him a bit, then laughing and trotting off. I recognized one of them as that same boy. I wanted to say something to him, now a teenager — to see if he remembered me, that nice guy who had lived in his building, who had let him hang out and talk while his mother was lost upstairs in a haze of heroin—but I just watched him disappear toward Avenue D, deep into the savage streets of Alphabet City, and wondered where kids like him end up, what their stories might sound like, hoping they might somehow be delivered from the tragic dice roll they’d gotten.

The Fender Stratocaster my brother, Gene, had given me was my only possession other than a chair and a mattress. I had no dresser. The clothes I wore were primarily bought from the open bins in front of Canal Jean Co., a remainder store on Canal Street (it would eventually move to a building on Broadway in SoHo). Shirts, trousers, and shoes could be had for a dollar a pop there. They were all “irregulars,” mistakenly sewed such that buttons didn’t quite match buttonholes, for instance. They weren’t considered very hip by any contemporary boutique standard, which at that time favored either hippie-funk flash or colorful-disco glam. The “look” of downtown no wave wasn’t retail-supported. If it aspired to anything, it was the uptown aesthetic of Fiorucci or the London-punk influence of Trash & Vaudeville on St. Mark’s Place. But those places were prohibitively expensive, especially compared with Canal Jean, and people on the downtown punk streets tended to struggle to make ends meet.

The clientele at CBGB and Max’s didn’t dress punk in any way that would have been endorsed by London’s King’s Road—no bondage gear, safety pins, or teddy boy accoutrements. If you walked into a club looking like that, it would be obvious that you were from way out of town or had seen pictures in magazines and thought that was what punk was. Or else it simply meant you had money.

The button-down shirts from the Canal Jean bins had tiny collars, and the trousers were all straight-legged and cuffed, a bit of a neo-bumpkin look about them—particularly when the trousers rode above the ankles, a fate I had more or less accepted for myself, being so tall. I certainly wasn’t the only poor art-rock nerd outfitting myself from these rag boxes. The entire no wave scene, all of whom seemed to live in and around my home on Thirteenth Street and Avenue A, was wearing the same duds.

The skinny ties and skinny-lapel suit jackets many of us sported, also cheap and vintage, gave the scene a derelict yet debonair feel. The inexpensive winter coats most commonly available at Canal Jean were made from old-man tweed, the kind a 1950s private detective would wear. When walking into Tier 3 or Mudd Club, it was obvious that we all had shopped, or stolen, from the same bins.

I had devoured Mickey Spillane books growing up — Mike Hammer, Spillane’s protagonist, ruminating about how he loved the summer rain, as it washed away the scum of New York’s infested streets. Manhattan still had a bit of Mickey Spillane in it during the 1970s, at least in the no wave clubs below Canal Street where I hung out. Bands like the Lounge Lizards, led by John Lurie and his younger sibling, Evan, both of whom looked like they were straight out of a noir flick, wore the style perfectly, accompanied by dangling cigarettes and blue-mood sax and piano.

Sonic Life: A Memoir

bookshop.org

$32.55

There was a young Latino couple living on the ground floor of my building. They knocked on my door one day and gave me some pro-socialist literature, asking if I would be interested in organizing a protest against the landlord, who, typically, was lax about protecting the building and raised rents without explanation. They invited me into their apartment for coffee, the place nearly as spartan as mine: all they had was a bed, a hot plate, and a large, ripped poster of Che Guevara on the wall.

I was noncommittal. I didn’t have any point of reference for their activism, as a geeky kid from Connecticut whose only experience with protest was when my father took me to a peace march after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, ten years prior. Sometime after our meeting, I heard a commotion downstairs—the landlord had shown up with some muscle to forcibly evict the insurgent couple.

I needed an amp if I wanted to really play my Stratocaster, and I eventually procured a tiny one at a Connecticut yard sale. I played in my apartment, noise that could most likely be heard by other tenants, but it was no louder than any of the yelling and stomping going on all day and night. At some point, new people moved in across the hall, and one evening I heard a tap tap on my door. It was a petite, pretty Latina girl in a bathrobe asking if she and her boyfriend could send an extension cable through their back window, across the airshaft, and into my apartment, so they could feed off my electricity until they got their payments together. They would pay me for what they used, of course. I acquiesced. She kindly queried about my guitar too and about me being a musician.

After about a week I realized I was being conned. These cats were never going to pay their share of my electric bill. So I unplugged them. My neighbor came over again, wondering what happened. I said I felt like one week was enough and that they should find another solution. The next night when I entered my apartment, I noticed the door was unlocked. Someone had come in and plugged the cable back in. From what I could tell, they had crawled on a plank between the two airshaft windows, reconnected the electric cord, then walked out my door, unable to lock it behind them.

The boyfriend had a rather imposing vibe, so I didn’t confront him, I simply unplugged the power again. The next time I returned, the same thing—cord plugged back in, door unlocked—but now the Fender Stratocaster my brother had given me, my small guitar amp, and my cassette player were missing.

I knocked on their door and the girl answered. I explained the scenario. I could see her boyfriend sitting on the couch with another dude watching TV.

“It wasn’t us”

— he said, not looking at me.

His friend, also not taking his eyes off the TV, added —

“You shouldn’t live in this neighborhood.”

I realized that if I disconnected them again, I might be attracting more than theft. So I left the extension cord plugged in and hoped they would eventually recognize how lame this situation was for me, their nice neighbor.

A few days later I heard yelling in the hallway. It was the landlord, once again, accompanied by yet more thugs. He threw my electricity-cadging neighbors out. It seems they hadn’t paid him any rent since they’d first moved in. The landlord saw me checking the scene out, then pointed his finger at me and warned—

‘‘And I better not have any more trouble from you!”

I wasn’t entirely innocent. I too could be a bit in arrears with my monthly nut.

All I had left to my name were my single bed mattress plopped on the floor, a tottering stack of books I had procured from various secondhand bookshops around town, and two cassettes—the Rolling Stones’ Some Girls and Bob Marley’s Exodus—with nothing to play them on. I was heartbroken at having the Stratocaster suddenly gone. It wasn’t the last time a guitar of mine would be ripped off, but it was the most jarring, my innocence at once vanquished, an initiation into the big, bad world of the big, bad city.

I didn’t have many friends in the neighborhood, even if I recognized some musicians and artists my age prowling around. Over on Twelfth Street between Avenues A and B was an infamous apartment where the no wave rat pack of James Chance, Sumner Crane, Lydia Lunch, and Jim Sclavunos were living together. A block west, in the building Jack Kerouac had lived in two decades prior, was where Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, Arthur Russell, and Richard Hell were currently decamped.

The only way I could pay the rent for my own modest dwelling was to borrow it from my mother, but that couldn’t go on forever. I scanned the want ads and saw that I could make a few bucks taking part in a drug-testing experiment. I went to the location in the ad, somewhere off Fourteenth Street around Union Square, and, at eight in the morning, got in line with a collection of street crazies, punk psychos, and a few relative innocents like myself. We were to get a hypodermic needle stuck into our arms full of some experimental vaccine, then to sleep the night on prison style bunks in a large warehouse space. Easy enough money, I thought.

I received the shot and prepared myself to bed down, all the while listening to the jabber of the maniacs around me. I looked forward to receiving my paycheck the next morning—thirty fat dollars. Within a few hours, though, I felt violently ill and began to puke endlessly into a bucket by the bed. Only a few of us were in such a state; most of the others were getting through it, whatever “it” was.

The following morning, after collecting the dough, I decided that I should probably find another source of income.

So I became a foot messenger.

As a foot messenger I walked through every neighborhood in Manhattan, entering countless buildings, peeking into strange apartments, once in a while receiving a tip, which I would generally use for a subway token to lighten the burden the miles put on my legs. The pay was entirely insufficient; as I walked, I would keep my head down, scanning the pavement for the gleam of errant coins. A few dollars gathered were enough to buy me a ticket on either the Metro-North train to Bethel or the less expensive Hudson line to Brewster, New York, a half hour outside Bethel, at which point I could hitchhike to my mother’s house for a little decompression.

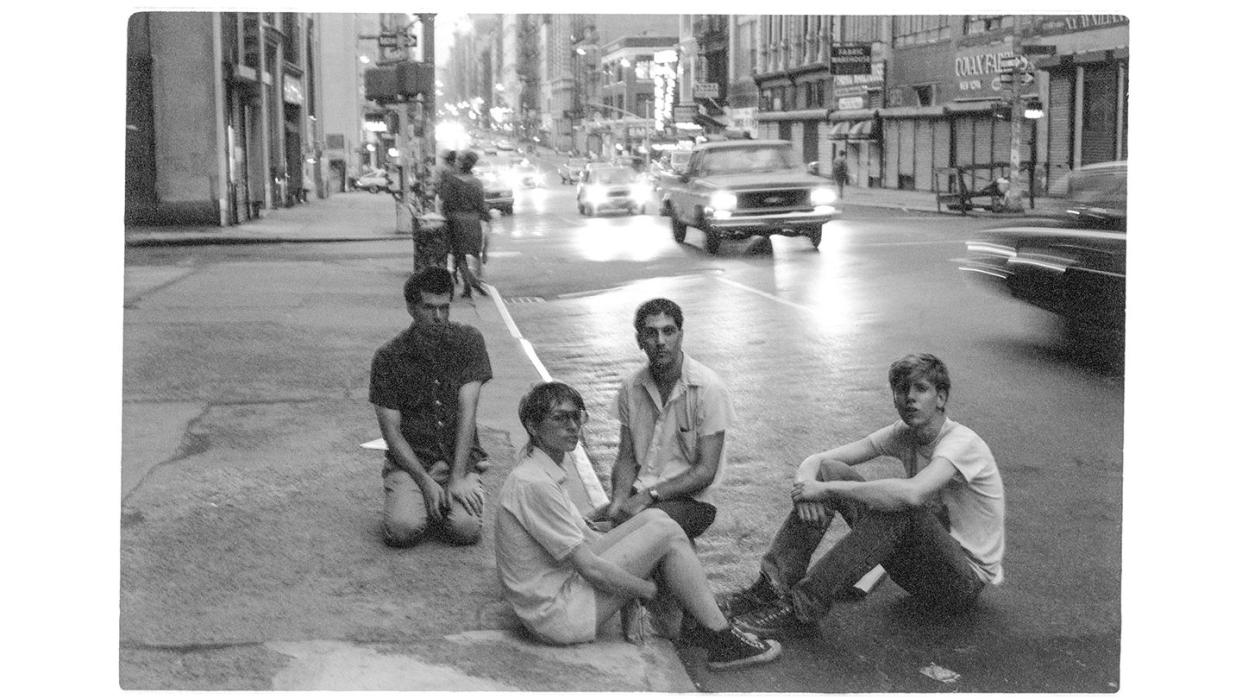

New York City in the summer of 1978 was at the bottom of its nosedive. With growing economic disparity, street crime was a normalized part of daily life. There was a general attitude of weary resignation. But there was also a shared sense, among my peers, that we were living in this city for the ineffable connection it afforded us—the wild community of artists, poets, and musicians giving voice to an environment rife with trash, chaos, and absurdity.

Spying Joey Ramone, Johnny Thunders, Lydia Lunch, Howie Pyro, Pat Place, Neon Leon, James Chance, or Cheetah Chrome and his amazing girlfriend, Gyda Gash, walking on the streets in sunlight, it was as if I were seeing owls who, through some error, were out and about during the daytime. They would appear to me like characters out of a Fellini film, as they stepped over spilled garbage cans or dodged around uncorked fire hydrants shooting water onto broiling concrete.

In the summer, almost everyone was out on the streets, sitting on building stoops or in cheap folding chairs on the sidewalks. The cost of air-conditioning was a luxury to most anyone living below Fourteenth Street. Along with fire engine and cop car sirens, the sounds of Mister Softee ice-cream trucks, their prerecorded music a worn-out, wobbling tape loop, would serenade us in the late afternoons.

The Sex Pistols had come over to tour the USA in January 1978, but, by manager Malcolm McLaren’s decree, they didn’t play the major outposts of New York City or Los Angeles. Instead, the punk lords plowed through Georgia, Tennessee, Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma, ending it all with a bedraggled performance at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, California, where they would unceremoniously split up.

Punk rock had by then entered an alternate reality, for those of us devoted to its glory. To hear jokes about Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, the highest-profile television program in the U.S., could only suggest that an end was near. Word went around that the Pistols were going to play New York City after all, despite the news of their apparent breakup, but it was not to be.

McLaren still had plans for his musicians. He whisked guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook off to record in Rio de Janeiro, with vocals by Ronnie Biggs—notorious as one of the infamous Great Train Robbers, by then escaped from English prison and living in exile.

As for Sid, he nearly OD’d after the Winterland gig, then again on the way to New York, eventually making it to London, where he would reconnect with his girlfriend, Nancy Spungen of Philadelphia. After recording incredible cover versions of the Frank Sinatra nugget “My Way” and the Eddie Cochran rockers “Somethin’ Else” and “C’mon Everybody” and playing a gig at the Electric Ballroom with ex-Pistol bassist Glen Matlock and Damned drummer Rat Scabies, Sid left with Nancy for New York City, where they would live out their final days.

The two immediately hooked up with ex-New York Doll Jerry Nolan, who had just formed his own band, the Idols. Like Sid and Nancy, he was a straight-up junkie, subsisting on heroin substitutes from various methadone clinics around town.

Nolan set up the closest thing to a Sex Pistols gig to grace New York, an act initially called the Music Industry Casualties, to play Max’s Kansas City on September 7. When the ad first appeared in the Village Voice, it mentioned that Sid would be joined by the Dead Boys’ Cheetah Chrome and Jeff Magnum. By the following week, the group was listed simply as “Sid Vicious and his Crew.” The Dead Boys were booked to play CBGB that same night, so those maniacs weren’t likely to be involved; but Nolan’s bandmate in the Idols, guitarist Steve Dior, convinced the Clash’s Mick Jones, in town mixing their second album at the Record Plant, to join Sid’s group. It would be Jones, Nolan, ex-Doll Arthur “Killer” Kane, and Dior himself. This was the first time any member of the Clash would appear live in New York City (a good five months prior to the Clash’s seismic throwdown at the Palladium in February 1979).

Whomever the band’s lineup would ultimately comprise, there was no way Harold and I were going to miss it. Sid playing at Max’s was the closest thing to compensation we’d get for the Sex Pistols blowing off New York City earlier in the year. The general feeling around town was that, as denizens of the birthplace of punk, we had been ripped off by the band breaking up. The fact that the Pistols had died their crummy death in San Francisco of all places, the city where punk’s nemesis, the hippie, had been born, only added insult to injury.

Harold and I arrived at Max’s in the late afternoon of the seventh, knowing that the gig would be sold out pretty quickly. There were about twenty people in line along Park Avenue just above Fifteenth Street. We joined them and waited, waited, waited. Finally, after cramming our way into the upstairs room, we grabbed two seats at one of the long tables pointing to the tiny stage. The audience that filed in was a mix of the usual characters with a new French-speaking, leather-pants-wearing punk contingent.

Again we waited, waited, waited.

Finally the opening band, which no one wanted to see or hear, came on. They were called Tracx, and they were so not punk it didn’t even register as funny. No one had ever heard of this band before (or has heard from them since), and they got killed by the audience. For thirty minutes, it was nothing but jeers and hoots before Tracx slumped off the stage.

Again, we waited interminably for Sid to come on. The place was jammed, drunk, smoked out, shifting discernibly from bored to belligerent.

And then they came.

Pushing through the audience first was Sid, followed by ex-New York Dolls bassist Killer Kane, then Jerry Nolan hand in hand with Nancy Spungen, then drummer Steve Dior and, to everyone’s leaping heart, the one and only Mick Jones from the Clash.

They assembled behind the stage’s curtain. When Sid stuck his head through it to deliver the almighty Sid wink, we knew we were in for crazy times. The curtain at last scrolled open, and Mick Jones led the band through classic Dolls and Pistols originals, as well as the 1950s Eddie Cochran tunes Sid had recorded in London. Nancy was playing, to some degree, a tambourine.

The audience went ballistic through it all. Chairs and tables were decimated. People spat, threw drinks—pure mania. The leather-trousered French freaks pointed their fingers at the stage howling—

“Seeeed! Seeeed Veeeesshus!” After the first song a girl yelled—

“I love you!”

—to which Sid responded in his North London street drawl,

“Shut your fucking mouth, you stupid fucking cunt.”

I had seen bands get spit on before. The musicians would usually scowl or, worse, complain. Sid spat back. You could see his goobers plonking into the French punks’ eyeballs.

This was waaay better than any old Sex Pistols gig would have been. This was the flower and the poison in one glorious crash and burn.

Excerpted from SONIC LIFE: A Memoir by Thurston Moore. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, an imprint ofThe Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2023 by Thurston Moore.

You Might Also Like