How the much-derided Eiffel Tower won the hearts of Parisians (and the world)

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

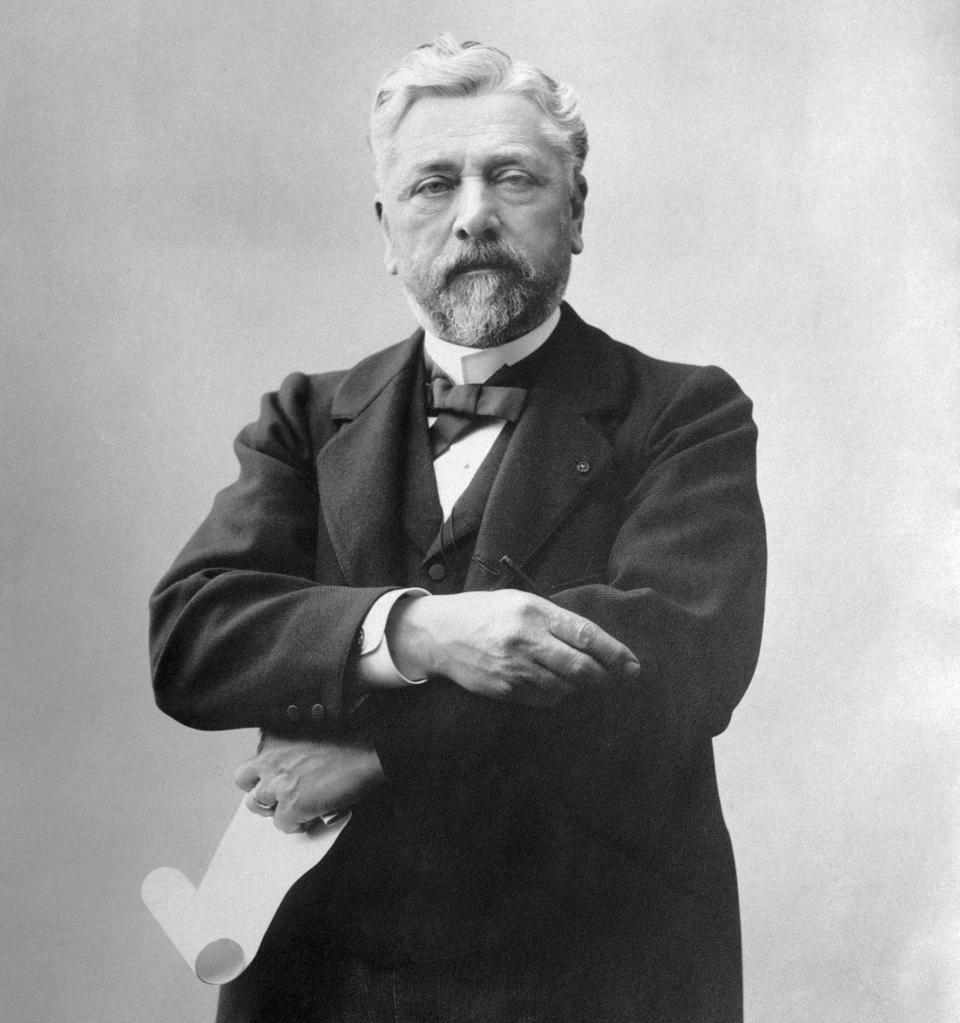

In the race to the top of the 19th century, Gustave Eiffel won by a country mile. Or, rather, by 143 metres. Eiffel’s tower, at 300 metres, almost doubled the previous “tallest structure” record – held by the Washington Monument since 1884. Prior to that, Cologne cathedral’s 157 metres had been the challenge to beat. It was a great moment, France with its Mr Toad side out. The country had had a military drubbing by the Prussians two decades earlier. Britain was steaming ahead, industry-wise.

Thus, the French needed to celebrate the centenary of their revolution with a power statement. Whence the 1889 Paris World Fair. And central to the impact of the World Fair was the biggest tower – the biggest “building” – in the world. It was tall, it was fantastic, it was useless. “Ohh, the bliss! Ohhh… poop, poop!” as Mr Toad put it. Mr Eiffel – who, on December 27, will have been dead for a hundred years – had stuck it to the world.

Through the 19th century, height had been an obsession in international construction circles (as it remains: see the excitement over the Burj Khalifa, biggest ever – more than two and a half times the Eiffel tower – in Dubai). A thousand feet was the goal. A couple of fellows had tried for the world fair in Philadelphia in 1876. Another had envisaged a vast granite column in Paris. Technical difficulties defeated them.

Only Eiffel, the greatest structural engineer of his time, overcame the problems – though even he didn’t quite make the thousand feet. Not initially, anyway. Three hundred metres comes in at 984 feet. It remains an astonishing feat. It wasn’t overtaken for 40 years, when New York’s Chrysler Building thrust up to 319 metres. (New aerials in the 1950s added 30 metres to the tower, so it then overtook the Chrysler.)

In the first instance, Eiffel wasn’t particularly interested in the tower project. He already had an international reputation following the success of the Garabit viaduct in the Massif Central and rail bridges in Bordeaux and, especially, Porto. His engineering business had its hands full with smaller contracts around the world.

But then three of his senior staff came up with workable plans for an iron tower. The boss was convinced. He swung in behind, using formidable PR and networking talents to get the job ahead of rival schemes. His offer to provide 80 per cent of the cost doubtless helped.

So the Eiffel men cracked on, in the teeth of serious opposition – notably, from artists and writers. The tower was to be “an odious column of bolted metal”, claimed an open letter signed by, among others, Charles Gounod, Alexander Dumas and Guy de Maupassant. Novelist and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans said it resembled “a hole-riddled suppository”. All of which reminds us that the average Parisian intellectual needs a regular slapping.

Part of Eiffel’s genius was to pre-assemble elements of the tower’s 18,000 puddle iron parts – with millions of heated rivets – at his base in Levallois-Perret, before final assembly, lattice-work style, on site on the Champ de Mars. Other innovative aspects of the construction abounded. Particularly notable, though, was the low death toll. Only one man died among a 300 on-site workforce, most of whom spent their time trotting freestyle along metal beams hundreds of feet above the ground. Photos show them nonchalantly leaning against struts and smoking, clearly unaware of the existence of vertigo.

In just two years, two months and five days, the tower was finished. Gustave Eiffel, then 57, climbed the 1710 steps to the top, bearing the French flag. Despite the disapproval of right-thinking people, it flourished immediately. Some two million visitors either climbed the stairs or used the hydraulic lifts during the World Fair. Eiffel was making his money back.

And then he got into big trouble elsewhere. Eiffel’s involvement in the building of the Panama Canal backfired spectacularly when the pharaonic project went bust. Hundreds of small investors were ruined. Eiffel shared the blame. It was alleged he had coined it. He was vilified across France. The courts agreed, condemning him, in the first instance, to two years in jail and a big fine.

He was cleared on appeal. But after the episode Eiffel quit the construction business. He developed instead his interest in meteorological and aerodynamic research. A wind tunnel he created is still in use in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. He also had to spend time securing his tower’s future.

At the outset, the tower was intended to be temporary, due to be dismantled after 20 years. But, by establishing a weather station on top, then adding radio aerials for the military, Eiffel ensured it endured. Early on, though, the tower established a parallel pattern of attracting lunatics and conmen. In 1912, Austrian-born tailor Franz Reichelt threw himself off, wearing “a parachute garment (designed to) preserve fliers from dangerous falls”. He apparently died before he hit the ground, though it’s unclear how they worked out the sequence.

Later, post-World War 1, Bohemian-born swindler Victor Lustig – who once conned Al Capone – “sold” the tower to one of France’s more gullible scrap metal merchants. The merchant was way too embarrassed to make official complaints, so Lustig was able to try to sell the tower again. This time, he was caught out.

Meanwhile, a replica tower – built in Blackpool in 1894 at 158 metres – was doing the business, not least because of its ballroom and, later, the great Reginald Dixon at the organ. Further copies followed. Most famous is the half-sized, 1999 version in Las Vegas. Others include two in China and one each in Paris, Tennessee and Paris, Texas.

Meanwhile, the race for height went on. After de-throning the Eiffel tower in 1930, the Chrysler Building was itself topped a year later by 381-metre, 102-storey Empire State Building. It in turn ceded its title to the first tower of the World Trade Centre in 1970 – and, to indicate how things have moved on, and up, ever since, is now but 54th tallest in the world. The world has, in 2023, 43 buildings over 400 metres high.

But none gets more visitors than the six to seven million who annually rise up the Eiffel Tower. (The Empire State Building receives four million.) Which I think is terrific, for a tower which has no real reason to exist, except that it does. It’s a Celebrity Big Tower, famous for being famous. Granted, there are aerials up top, but they could be disposed of with a great deal less flourish. In a sense, it’s a jolly huge, vertical seaside pier, built to do nothing except to be there, and please visitors. This is what distinguishes it from pretty much all other tall buildings, which have a purpose besides being tall.

And it really is beautiful. Up close, the tower is arrestingly huge – like Albi cathedral or Dwayne Johnson. But it is also light on its legs. Strike up an accordion and it might waltz off down the Champ-de-Mars. Take these elements together, and that’s why we like it. That’s why everyone takes a photo – though, obviously, the world needs more pictures of the Eiffel tower as it needs more snaps of kittens in baskets. The French are painting it gold for the 2024 Olympics. I have a feeling that only they could have pulled off such appealingly monumental superfluity. No wonder Mr Eiffel remains a hero.

How to do it

It costs £25 (per adult over 25) to take the lift to the top. Adding a glass of champagne from the top-floor champagne bar bumps that to £44. It’s £16 to go to the second floor. Book ahead on toureiffel.paris to avoid queues. The new-ish Madame Brasserie on the first-floor is expensive – from around £78 for three-course dinner – but not as expensive as the second-floor Jules Verne, whose five-course tasting menu is from £221. Book ahead at both (restaurants-toureiffel.com).