Mr. Chow Celebrates 50-Year Legacy with New Art Book

It’s difficult to understand the legacy of Mr. Chow if you weren’t around in the '60s and '70s. Restaurateur Michael Chow launched his eponymous first restaurant in a luxe London neighborhood in 1968, on Valentine’s Day. Reportedly, the Beatles and the Stones showed up. It instantly became a scene.

And many would say, it was the scene. Riding a wave of celeb-driven success, Chow opened two more locations in Beverly Hills and New York City in the '70s. They also attracted A-list regulars like Jack Nicholson, Federico Fellini and Yoko Ono.

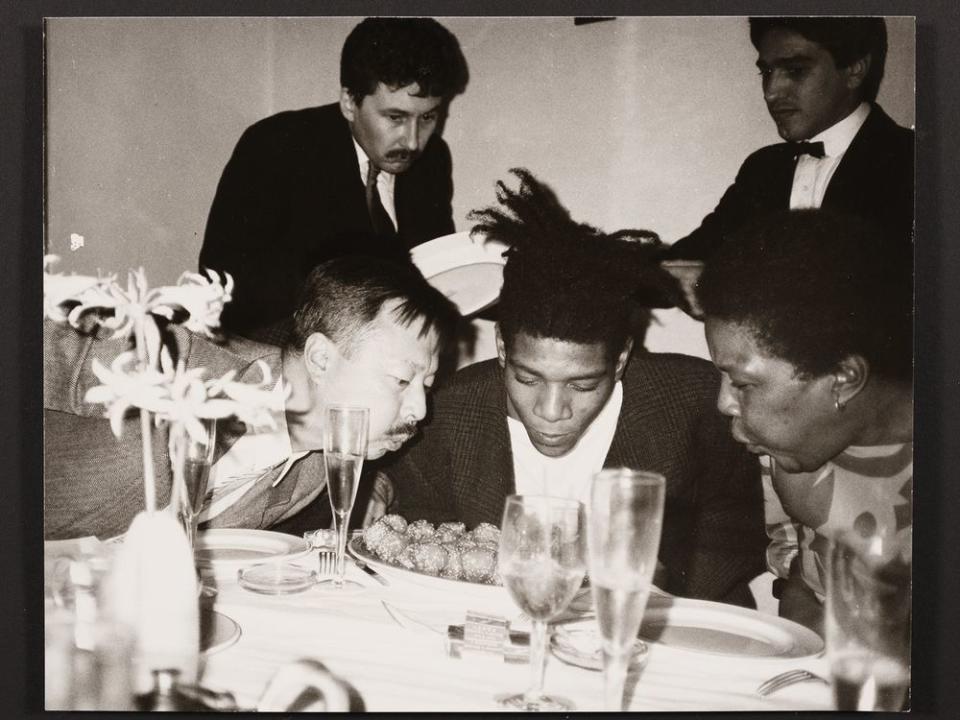

Andy Warhol became a friend, and even silkscreened two portraits of Chow—who goes simply by "M"—and both are in Chow’s upcoming book, MR CHOW: 50 Years. It’s a memoir-like, coffee-table tome of portraits and photographs of the restaurateur, rendered by the likes of Warhol (who also painted Chow’s ex-wife, Tina Chow) and Cannes-winning director Dennis Hopper. (Chow was previously married to model Grace Coddington in the late '60s, who later went on to be creative director at large at Vogue.)

MR CHOW: 50 Years will be released next year, in commemoration of the fiftieth anniversary of the London opening. It’s no small feat for a restaurant to be have survived for that long, but that’s not even why Mr. Chow is a big deal. And sure, it gained fame as a buzzy celeb hangout, but there are lots of those around.

What was really remarkable about it is how, at a time when American Chinese food was relegated to being cheap takeout, Mr. Chow highlighted refinement. You entered the restaurant and were met with French de?cor and Italian waiters; the table cloths were pressed, the cutlery heavy, the portions small and the prices high.

“People say, ‘Oh, it’s so expensive,’” Chow told the New York Times in an interview last year. “I say, ‘Fantastic!’ Expensive is important. Very important.”

An order of Beijing Duck at the Beverly Hills location, for example, runs $68. That’s not even all that pricey compared to many Michelin-starred restaurants out there; compare it to the $310 tasting menu at Thomas Keller’s French Laundry, for example. Some people have pointed out, however, that Mr. Chow isn’t Michelin-starred. Some would say the food leaves something to be desired, and the quality has dropped significantly.

Former New York Times restaurant critic Frank Bruni is one of those people. He famously gave the restaurant zero stars in 2006, citing, “Mr. Chow is the kind of restaurant whose opening is noted in Us magazine, not Saveur.”

While many might say it’s still worth it to come for the ambiance alone—the well-curated art, the Champagne pairings, the almost guaranteed celeb sightings—Chow has insisted the food isn’t an afterthought. Top chefs are recruited from Hong Kong and Beijing to parlay the cuisine in non-fusion style, he’s told the New York Times.

One thing is for certain, however: regardless of one’s opinion on Mr. Chow today, or whether one would readily drop $150 there, the restaurant’s culinary impact on American Chinese cuisine can’t be underestimated.

“Chinese food was supposed to be cheap,” Chow told the New York Times. “I changed all that. But it took me almost half a century.”

To call him a restaurateur would be reductive; he’s also an architect who’s designed boutiques for Giorgio Armani, as well as being an avid art collector. Just as his well-curated book posits, Michael Chow isn’t just friends with famous artists; he’s one himself. And his experience-driven, design-forward restaurants are a testament to that.